¡Ahora Sí!

by El Jekke y su Banda

Click here to download "¡Ahora Sí!" in MP3.

Ahora Vamos por el Sí

by Lloviznando Cantos

Click here to download "Ahora Vamos por el Sí" in MP3.

"Method of this project: literary montage. I needn't say anything. Merely show." -- Walter Benjamin

¡Ahora Sí!

by El Jekke y su Banda

Click here to download "¡Ahora Sí!" in MP3.

Ahora Vamos por el Sí

by Lloviznando Cantos

Click here to download "Ahora Vamos por el Sí" in MP3.

The decision was primarily a result of the fact that the delegations of the United States and the Soviet Union, which were at loggerheads on every other important issue before the Assembly, stood together on partition. Andrei A. Gromyko and Herschel V. Johnson both urged the Assembly yesterday not to agree to further delay but to vote for partition at once. (Thomas J. Hamilton, "Assembly Votes Palestine Partition")The Soviet role in the partition of Palestine and the establishment of Israel was the biggest blow against socialism in the Middle East, as Jordanian Marxist Hisham Bustani argues in "Critique of the Arab Left: On Palestine and Arab Unity" (MRZine, 19 November 2007), and Arab socialists have never quite recovered from it.

The New Monastics

by Dennis Brutus

Tall black-shadowed cypresses

slender beside arcaded cloisters:

thus were monastic enterprises:

now with our new doctrines

secular-consumerist we bend

with similar devoutness in service

to our modern pantheon --

Bretton Woods, its cohort deities

-- World Bank, IMF, WTO --

diligently we recite

"We have loved, o lord, the beauty of your house

and the place where your glory dwells"

"Amen" we chorus in unison

as ordered by our Heads of State

obediently we traipse to our slaughterhouse

directed by our Judas-goats

Mbeki's herds tricked out in shabby rags

discarded by imperialist gauleiters

who devised our Neepad subjugation

ActionAid Economic Justice course,

Kenyan School of Monetary Studies

Nairobi, November 26, 2007

The stated goal of Mr. Bush's first serious stab at Middle East peacemaking is to revive negotiations between Israelis and Palestinians to end the region's most enduring conflict. But administration officials hope progress in talks scheduled to begin Tuesday in Annapolis, Md., also curries favor with skeptical Sunni Arab leaders, whom the U.S. needs to check Iran's growing regional clout.Naturally, the Turks are playing both sides of the game, hosting the Istanbul Al-Quds International Forum (at which four Iranian delegates were guests) and mediating Israel and Syria: "Mr. Olmert has used Turkish intermediaries to explore options with the Syrians, according to Israeli officials" (Simpson and Solomon, 24 November 2007).

Underscoring that effort, the Bush administration is even courting a long-time pariah, Syria. Syria's bitter enemy, Israel, is going even further, indicating that its arms are open wide to Damascus. Talks with Syria could go some way in weakening Tehran's strongest alliance in the region.

"This is one of those moments in history where the Syrians have been given an opportunity to jump," a senior Israeli official said this past week. "If they do jump, they will be embraced."

On Sunday, Syrian officials reported that the country will be represented at the conference by Deputy Foreign Minister Faysal Mekdad because the issue of the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights has been added to the agenda, according to The Associated Press. (At Mideast Talks, U.S. and Israel Seek to Isolate Iran by Wooing Syria, 24 November 2007, p. A1)

by Emad Hajjaj

Percentage of Democrats who think that Hillary Clinton is proposing to withdraw all U.S. troops from Iraq within a year: 76That means that we have failed to educate even Americans who are opposed to the Iraq War, let alone the rest of the nation.

In the mid '70s, when this film was produced, it created a storm of controversy, and encountered censorship problems in several countries, not just Japan. Its explicit treatment of sexual intercourse and its bloody castration scene outraged and disturbed viewers brought up on Hays Code morality. It was an international sensation, provoking packed houses and lively debate at the 1976 Melbourne Film Festival.Freiberg laments the passing of the time of sexual dissidence, but that is perhaps a welcome sign that sex has become unremarkable -- just a part of everyday life, as Araki has always insisted.

Now, 25 years later, its re-release in the original uncut version has passed almost unnoticed by viewers in Melbourne, despite the plaudits of film critics. It has become a classic, but not a cult classic apparently. That is the unkindest cut of all. The public's lack of interest serves to remind us of all those clichés about yesterday's sensation and the ephemerality of fame. ("The Unkindest Cut of All?" Senses of Cinema 12, February-March 2001)

Pirates lurking off the coast of Somalia have attacked more than 20 ships this year, including two carrying United Nations food. The militias that rule the streets -- typically teenage gunmen in wraparound sunglasses and flip-flops -- have jacked up roadblock taxes to $400 per truck. The transitional government last month jailed a senior official of the United Nations food program in Somalia, accusing him of helping terrorists, though he was eventually released.Ideologues make the empire out to be a progressive force for modernity and pass off all its adversaries as a reactionary force against it. The reality is the opposite. The effect of imperialism delays the development of modernity at best and at worst destroys the minimum necessary condition for its establishment: a national government.

United Nations officials now concede that the country was in better shape during the brief reign of Somalia's Islamist movement last year. "It was more peaceful, and much easier for us to work," Mr. [Eric] Laroche [the head of United Nations humanitarian operations in Somalia] said. "The Islamists didn't cause us any problems."

Mr. [Ahmedou] Ould-Abdallah [the top United Nations official for Somalia] called those six months, which were essentially the only epoch of peace most Somalis have tasted for years, Somalia's "golden era."

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

"We want the Islamists back," said Mohammed Ahmed, a shriveled 80-year-old retired taxi driver.

Mr. Mohammed said he was not especially religious. "But," he said, "at least we had food." ("As Somali Crisis Swells, Experts See a Void in Aid," 20 November 2007)

"I have enough dynamite stored up at the mountain to send it down crashing into the valley" -- his [Charles's] voice rose a little -- "to send half Sulaco into the air if I liked." . . . "Why, yes," Charles pronounced, slowly. "The Gould Concession has struck such deep roots in this country, in this province, in that gorge of the mountains, that nothing but dynamite shall be allowed to dislodge it from there. It's my choice. It's my last card to play." (Nostromo, Part 2 "The Isabels," Chapter 5)

| Voltaire y el islam por Juan Goytisolo En su vehemente proceso al islam y al estatus de inferioridad legal y de sumisión de la mujer que prevalece en la mayoría de países musulmanes, Telima Nesreen, Ayaam Hirsi Ali y otras emancipadas de su credo religioso han evocado y evocan repetidas veces el nombre del autor de Cándido: "Permitidnos un Voltaire . . . Dejemos a los Voltaire de nuestro tiempo trabajar en un entorno seguro en el desarrollo de una época de ilustración para el islam". El llamamiento es en términos generales justo y merece nuestro apoyo, pero exige una serie de matizaciones, no sólo por la variedad de situaciones existentes en el ámbito musulmán, sino también por la multiplicidad de posiciones, a menudo contradictorias, que adopta Voltaire en el tema. Reducir su vastísima obra a la tragedia Mahoma o el fanatismo escrita en 1739 y estrenada en la Comédie Française en 1742, equivale a limitarla a un periodo muy breve de su labor filosófica y literaria. Un recorrido por sus casi inabarcables Obras Completas nos muestra que el "patriarca de Ferney" y amigo de los grandes de este mundo, como Federico II de Prusia y de Catalina la Grande, no cesó de exponer sus ideas, opiniones y sentimientos respecto a los que llamaba "mahometanos" --denominación errónea, pero común en su tiempo-, en ensayos, artículos de la Enciclopedia, cuadernos personales, correspondencia, novelas y obras teatrales. Si los cálculos no me fallan, más de una treintena de textos, como dice Etiemble, "en su edad adulta y en su vejez, Voltaire no dejó de informarse [sobre el profeta y su religión] con una avidez no reñida con el discernimiento". Ante la imposibilidad de extractar aquí tal masa de documentos en los que el autor reitera con otras palabras lo ya dicho, lo modifica y, muy a menudo, lo contradice, he recurrido al excelente libro de Djevad Hadidi, Voltaire y el islam, editado en 1974 por Publicaciones Orientalistas de Francia y que, lamentablemente, no ha sido traducido aún al español. Desde la imparable expansión del Imperio Otomano por los Balcanes y el norte de África -- especialmente tras la caída de Constantinopla y tentativa de apoderarse de Roma --, el interés de los cronistas franceses por las Cruzadas y la presencia de los sarracenos en la península Ibérica cedió paso a una creciente fascinación, entreverada con envidia y temor, por los turcos. Hasta el siglo XVI, la visión de Mahoma y los agarenos respondía a las leyendas forjadas en la llamada Reconquista, cuyo contenido mítico y extravagante analizó Edward Said en Orientalismo. Dicha literatura de índole religiosa y militante, a la que el joven Voltaire tuvo acceso por sus lecturas de Buffier, Maracci y Bossuet, se vio desbancada de pronto por la de los viajeros a la nueva Meca del Bósforo. La masa de observaciones, datos y comentarios referentes al "capital enemigo de la Cristiandad" crearon un verdadero grupo de presión proturco, compuesto en su inmensa mayoría por hugonotes y luteranos: Guillaume Postel, Philippe de Fresne-Canay, Tavernier, Chardin, D'Hebertot, Tournefort, etcétera, autores que leí con atención en la fase preparatoria de Estambul Otomano (y a ellos habría que añadir al padre del extraordinario Viaje de Turquía, probablemente el protestante español Juan de Ulloa, juzgado y reconciliado en el auto de fe de Valladolid de 1554). Aunque por las fechas en que compuso la tragedia, Voltaire profesaba ya su doctrina deísta -- la de una "religión natural" no corrompida por ninguna clase de preceptos ni dogmas --, no tuvo en cuenta los conocimientos aportados por la corriente ideológica favorable a los otomanos que desmentían las toscas invenciones y fábulas de la tradición devota. En Mahoma o el fanatismo, su retrato del profeta como un hombre exaltado, ambicioso y buen conocedor de los mecanismos del alma humana favorables a la consecución de sus fines va acompañado de epítetos denigrantes sobre su carácter y falsos milagros. En realidad, si leemos cuidadosamente el texto, el ataque a Mahoma encubre otro: el dirigido al Mesías de los cristianos y a los profetas bíblicos. Una buena parte del público parisiense lo entendió así: los jansenistas se sintieron aludidos y arremetieron contra la obra. Si seguimos por orden cronológico los escritos posteriores, desde Sottisier (Disparatario o Repertorio de sandeces, germen sin duda del Diccionario de ideas comunes de Flaubert) hasta Ensayo sobre las costumbres, fechado en 1756, vemos perfilarse los temas centrales de Voltaire --odio al fanatismo, impugnación de las religiones reveladas, denuncia de la alianza de intereses celestes y terrenales para empujar a la guerra a los exaltados -- paralelamente a una profundización de sus conocimientos sobre el islam y los otomanos, fruto de su amistad con Boulainvilliers y de su lectura de la traducción inglesa del Corán. Mientras la crítica a Jesús, tildado de fanático y alienado en sus Epístolas filosóficas, se acentúa, su visión de Mahoma se suaviza al punto de concederle cualidades de justicia y tenacidad: "El legislador de los musulmanes, hombre dominante y terrible, estableció sus dogmas con su valor y con las armas; con todo, su religión se volvió benigna y tolerante. El institutor divino del Cristianismo, viviendo en la humildad y en la paz, predicó el perdón de las injurias; y su santa y dulce religión se ha convertido, por nuestros furores, en la más intolerante de todas y la más bárbara". (Ensayo sobre las costumbres, capítulo VI). En el cambio operado en el intervalo ha intervenido su ya asentada, aunque sujeta a vaivenes y fluctuaciones, admiración por los otomanos. La evocación de las hogueras inquisitoriales para los judíos portugueses en Cándido, en contraposición a las jocosas aventuras del protagonista en la corte del Gran Señor, así como las andanzas de Scarmentado, héroe de su deliciosa novela Zadig, por tierras del Sultán, se adscriben a la tradición proturca de los hugonotes, al punto que Voltaire fue calificado por sus adversarios de "patriarca in petto de Constantinopla". En Tratado sobre la tolerancia -- escrito a raíz de la ejecución de varios librepensadores como Calas y el chevalier de La Barre, cuya estatua conmemorativa de su juvenil rebeldía me mostró en Abbeville Jean Genet -- Voltaire se lanza a una elocuente defensa del turco: "El Gran Señor gobierna en paz a veinte pueblos de religiones distintas; doscientos mil griegos viven en paz en Constantinopla; el muftí en persona nombra al patriarca griego y lo presenta al emperador" (sic), y el imperio, añade, "está lleno de jacobinos, nestorianos y monoteístas". Las guerras intestinas entre cristianos -- como las que desgarran hoy el mundo islámico -- atizan su indignación contra el fanatismo, responsable, dice, de todos los males del mundo. Años después, en "La profesión de los deístas", denunciará que mientras los cristianos a orillas del Bósforo portan libremente a su Dios por las calles, en Europa "se condena a la horca o la rueda a cualquier predicador calvinista y a galeras a quienes le escuchan". A lo que Voltaire añade: "¡Oh naciones, comparad y juzgad!". La coexistencia de diferentes credos correspondía al deísmo del filósofo -- que nada tiene que ver, no lo olvidemos, con el ateísmo de Diderot -- : a su profunda convicción, que hoy denominaríamos multiculturalista, de que la tolerancia favorece el intercambio de ideas por encima de las creencias y de que, como señala Hadidi, fomenta el progreso material y moral, al mantener la paz y la prosperidad en el interior de los Estados. Pero, en su entusiasmo del momento por el modelo otomano, Voltaire llega a una sorprendente defensa de la poligamia, "útil a la sociedad y a la propagación" (de la especie), ya que "el tiempo perdido por los embarazos, los pañales, por las incomodidades propias de las mujeres, parece exigir que dicho lapso sea compensado" (¡) Más perturbador aún: en su artículo titulado irónicamente "Mujeres, sed sumisas a vuestros maridos", el autor admirado por Ayaam Hirsi Ali y otras feministas, tal vez sin haberlo leído con detenimiento, opina no sólo que Mahoma fue más generoso con ellas que David, Salomón y quienes los justificaron a posteriori como los santos Padres de la Iglesia -- lo cual es hasta cierto punto verdad --, sino también, y en contradicción con la aleya 38 de la "Sura de las mujeres" del Corán, niega que los varones musulmanes tengan autoridad sobre ellas y les exijan obediencia, algo que sí, agrega, les imponía San Pablo. Como vemos, a lo largo de su vasta y a menudo admirable obra, Voltaire yerra, rectifica, se contradice. Su odio a la figura de Jesús se atenúa conforme entra en la vejez. Su apreciación de Mahoma, en cuanto fundador de "una religión sabia, severa, casta y humana", no obsta para un persistente rechazo a su figura. La inmensidad del corpus doctrinal volteriano contiene infinidad de facetas y se presta a contradictorias lecturas. El autor de Cándido y Zadig -- en cuya relectura no ceso de recrearme -- sufría además las turbulencias de la ambición y de su condigna lisonja a los monarcas que le protegieron y con quienes se carteaba con desenvoltura. Para ellos, Federico II de Prusia y la zarina rusa, proyectó una cruzada contra sus admirados otomanos, con miras a deshacerse de los "usurpadores" del trono de los Constantinos y de los Marcos Aurelios, esto es, del Sultán y del Papa. Mas dichas veleidades y errores valen poco frente a su condena radical del fanatismo y de toda creencia dogmática. Volviendo al comienzo: el mundo islámico de 2006 necesita muchos Voltaire para salir de su atraso, ignorancia y de las luchas sectarias que le desgarran. El cambio de estatus de la mujer, este subproducto nocivo de raíz bíblica -- la fórmula es mía, no de Voltaire -- constituye un instrumento indispensable para todo proyecto modernizador y algunos pasos recientes en la buena dirección deben ser alentados. Pero, junto al Voltaire radical en su lucha contra la intolerancia, hay mucho que aprender también del que se esforzó en analizar con pragmatismo la diversidad y antinomias de las sociedades musulmanas de su siglo, por muy diferentes que sean de las del nuevo milenio. Nada peor para nuestro futuro que recurrir, como los doctrinarios exaltados de hoy, al viejo espíritu de las Cruzadas. | Voltaire and Islam by Juan Goytisolo In their vehement prosecution of Islam and the state of legal inferiority and submission of women that prevails in a majority of Muslim countries, Taslima Nasreen, Ayaan Hirsi Ali, and other emancipated women of their religious creed have invoked and repeatedly invoke the name of the author of Candide: "Permit us a Voltaire. . . . Let us allow the Voltaires of our time to work in a safe environment on the development of an epoch of enlightenment for Islam." The call is in general terms just and merits our support, but it demands a series of qualifications, not only for the variety of existing situations in the Muslim world, but also for the multiplicity of positions, often contradictory, that Voltaire takes on the subject. To reduce his vast oeuvre to the tragedy Mahomet or Fanaticism, written in 1739 and premiered at the Comédie Française in 1742, is tantamount to limiting it to a very brief period of his literary and philosophical work. A perusal of his almost boundless Complete Works shows us that the "patriarch of Ferney" and friend of the potentates of this world, like Frederick II of Prussia and Catherine the Great, did not stop expounding his ideas, opinions, and feelings about those whom he called "Mohammedans" -- an erroneous denomination, but common in his time -- in essays, Encyclopedia entries, personal notebooks, correspondence, novels, and theatrical works. If my math doesn't fail me, he did so in more than some thirty texts -- as Etiemble says, "in his adulthood and old age, Voltaire did not stop inquiring [on the prophet and his religion] with avidity that is not incompatible with discernment." Faced with the impossibility of summarizing here such a mass of documents in which the author reiterates with new words what he already said, modifies it, and, quite often, contradicts it, I have turned to the excellent book by Djavâd Hadidi, Voltaire et l'Islam, published in 1974 by Publications orientalistes de France, which, lamentably, still has not been translated into Spanish. From the time of the unstoppable expansion of the Ottoman Empire over the Balkans and North Africa -- especially after the fall of Constantinople and attempt to seize Rome -- the interest of French chroniclers for the Crusades and the presence of the Saracens in the Iberian Peninsula yielded an increasing fascination -- mixed with envy and fear -- with the Turks. Until the sixteenth century, the vision of Muhammad and Muslims corresponded with the legends forged in the call for Reconquista, whose mythical and extravagant content Edward Said analyzed in Orientalism. This literature of religious and militant nature, to which the young Voltaire had access through his reading of Buffier, Maracci, and Bossuet, was supplanted by that of travelers to the new Mecca of the Bosporus. The mass of observations, data, and commentaries referring to the "capital enemy of Christianity" created a veritable pro-Turkish pressure group, composed mostly of Huguenots and Lutherans: Guillaume Postel, Philippe de Fresne-Canay, Tavernier, Chardin, D'Hebertot, Tournefort, et cetera, authors whom I read attentively in the preparatory phase of Estambul Otomano [Ottoman Istanbul] (and to them it would be necessary to add the father of the extraordinary Viaje de Turquía [Turkish Journey], probably the Spanish Protestant Juan de Ulloa, judged and reconciled in the auto de fe of Valladolid in 1554). Although by the time when he composed the tragedy, Voltaire already professed his deist doctrine -- that of a "natural religion" uncorrupted by any class of precepts or dogmas -- he had yet to consider the knowledge contributed by the ideological current favorable to the Ottomans who contradicted the crude fables and inventions of the devotional tradition. In Mahomet or Fanaticism, his portrait of the prophet as an exalted and ambitious man well acquainted with the mechanisms of the human soul favorable to the attainment of his aims goes accompanied by epithets that denigrate his character and false miracles. In fact, if we read the text carefully, the attack on Muhammad conceals another one: the one aimed at the Messiah of Christians and Biblical prophets. A good part of the Parisian public understood it thus: the Jansenists felt themselves alluded to and attacked the work. If we follow later writings chronologically, from Sottisier (Folly or Repertoire of Nonsense, undoubtedly a source of Flaubert's Dictionary of Received Ideas) to Essay on Customs, dated 1756, we can see the central themes of Voltaire -- hatred of fanaticism, refutation of revealed religions, denunciation of the alliance of celestial and earthly interests to press the excitable toward war -- take shape in parallel to a deepening of his knowledge of Islam and the Ottomans, fruit of his friendship with Boulainvilliers and his reading of the English translation of the Qur'an. While the criticism of Jesus, labeled fanatical and alienated in his Philosophical Letters, is accentuated, his vision of Muhammad is softened to the point of granting him qualities of justice and resilience: "The legislator of the Muslims, a terrible and powerful man, established his dogmas with his valor and arms; yet, his religion became benign and tolerant. The divine founder of Christianity, living in humility and peace, preached forgiveness of outrages; and his holy and mild religion was turned, by our rages, into the most intolerant and barbarous of all" (Essay on Customs, Chapter VI). His already established, albeit variable and mercurial, admiration for the Ottomans played a role in the change made in the interval. The evocation of inquisitorial bonfires of Portuguese Jews in Candide, in contrast to the humorous adventures of the protagonist in the style of the Great Gentleman, as well as the adventures of Scarmentado, hero of his delicious novel Zadig, over the Sultan's territories, is ascribed to the pro-Turkish tradition of Huguenots, so much so that Voltaire was branded by his adversaries as "patriarch in petto [in the breast] of Constantinople." In his Treatise on Tolerance -- written as a result of the execution of several free-thinkers like Calas and the chevalier of La Barre, whose statue commemorative of his youthful revolt Jean Genet showed me in Abbeville -- Voltaire launches an eloquent defense of the Turk: "The Great Lord peacefully governs twenty peoples of different religions; two hundred thousand Greeks live peacefully in Constantinople; the Mufti in person names the Greek patriarch and presents him to the emperor " (sic), and the empire, he adds, "is full of Jacobites, Nestorians, and monotheists." Internal wars among Christians -- like those that are tearing up the Islamic world today -- arouse his indignation against fanaticism, responsible, he says, for all evils of the world. Years later, in "The Profession of Deists," he will condemn that, while Christians on the shores of the Bosporus parade their God freely in the streets, in Europe "any Calvinist preacher is condemned to the gallows or the wheel, and anyone who listens to him, to the galleys." To that, Voltaire adds: "Oh nations, compare and judge." The coexistence of different creeds corresponded to the deism of the philosopher -- which has nothing to do, let us not forget it, with the atheism of Diderot -- and to his profound conviction, which today we would call multiculturalist, that tolerance favors the interchange of ideas over beliefs and, as Hadidi points out, that it foments moral and material progress, while maintaining peace and prosperity within states. But, in his enthusiasm of the moment for the Ottoman model, Voltaire arrives at a surprising defense of polygamy, "useful to society and propagation" (of the species), since "the time lost by pregnancies, diapers, indispositions typical of women, seems to demand that this lapse be compensated"(!). More disturbing still: in his ironically titled article "Wives, Submit Yourselves to Your Own Husbands," the author admired by Ayaan Hirsi Ali and other feminists, perhaps without them having read him thoroughly, not only thinks that Muhammad was more generous toward women than David, Solomon, and those who justified them a posteriori as the holy Fathers of the Church -- which is true up to a certain point -- but also, and in contradiction to Verse 38 of the "Sura of Women" of the Qur'an, denies that Muslim men have authority over them and demand obedience of them, obedience that certainly, adds Voltaire, Saint Paul commanded. As we can see, throughout his vast and often admirable work, Voltaire errs, rectifies, contradicts himself. His hatred of the figure of Jesus diminishes as he enters his old age. His appreciation of Muhammad, as the founder of "a wise, severe, chaste, and humane religion," does not stop him from persistently rejecting this figure. The immensity of Voltairean doctrinal corpus contains an infinity of facets, and it lends itself to contradictory readings. The author of Zadig and Candide -- in whose rereading I never cease to take delight -- moreover suffered from the turbulences of ambition and its corollary adulation for the monarchs who protected him and with whom he corresponded with ease. For them, Frederick II of Prussia and the Russian Czarina, he planned a crusade against the Ottomans he admired, with a view to undoing the "usurpers" of the throne of the Constantines and the Marcus Aureliuses, that is to say, the Sultan and the Pope. But these errors and caprices are worth little in contrast to his radical condemnation of fanaticism and any dogmatic belief. Returning to the beginning: the Islamic world of 2006 needs many Voltaires to leave behind its ignorance, backwardness, and sectarian battles that are tearing it up. Change in women's status, an injurious byproduct of the Biblical origin -- the formula is mine, not Voltaire's -- constitutes an indispensable instrument for any modernizing project, and some recent steps in the good direction must be encouraged. But, besides the radical Voltaire in his battle against intolerance, there is also much to learn from the Voltaire who endeavored to pragmatically analyze the diversity and antinomies of Muslim societies of his century, no matter how different they are from those of the new millennium. Nothing worse for our future than to resort, like the extreme doctrinaires of today, to the old spirit of the Crusades. |

Selon leur habitude, les groupes ou individus de tendance intégriste s'attaquent d'abord aux droits des femmes. Cela ne se voit pas seulement dans des pays totalitaires où la religion sert de programme politique, mais aussi au Canada, aux États-Unis et en France, où l'État est censé être indépendant des pouvoirs religieux. . . . La montée de l’intégrisme religieux dans le monde n’est pas sans effet sur les sociétés canadienne et québécoise.Fundamentalist Islam is a problem in such countries as the Gulf states, but the author blows the problem out of its proportion by sounding a false alarm that Canada, of all places, is vulnerable to it. Just how many Muslims are in Canada? According to the 2001 census, Muslims constituted merely 2% of the total Canadian population, and their proportion was estimated to be about 2.5% in 2006, of whom only a tiny minority must be fundamentalists -- if anything, Canada's points system of immigration, which favors the better off and better educated, means that many Muslim immigrants in Canada, like other immigrants, tend to be liberals of the "professional-managerial class" (to use Barbara and John Ehrenreich's term), given the correlation among class, education, and ideology.

As is their habit, groups and individuals of the fundamentalist tendency initially attack the rights of women. That is seen not only in totalitarian countries where religion serves as the political program, but also in Canada, the United States, and France, where the state is supposed to be independent of religious powers. . . . The rise of religious fundamentlaism in the world is not without effect on Canadian and Québécois societies. (Micheline Carrier, "Est-ce de l'islamophobie de critiquer l'intégrisme islamiste ?" Trans. Yoshie Furuhashi, Sisyphe.org, 21 November 2007)

In 1950, the US supplied 50% of the world's gross product; by 2003 this had dropped to 20%. In 1950, 60% of all manufactured goods were produced in the US, today only 20% of manufactured goods derive from the US. Non-US companies now dominate most of the industries in the world. For example, 9 of the 10 largest electronics companies, 8 of the 10 largest car manufacturing companies, 7 of the 10 largest oil companies, and 19 out of the 25 largest banks in the world are non-American. (Shawn Hattingh, "The G20: The New Ruling Aristocracy of the World?" MRZine, 15 November 2007)Washington has responded to this paradox by building multilateral institutions such as the G7, and later the G20, the latter of which incorporates not only China and Russia but also such regional powers as Brazil, India, Turkey, and South Africa into the multinational empire, albeit as subordinate members. Iran's "moderates" would love to integrate Iran, under their leadership, into this still US-led project -- hence the aforementioned message to the West -- rather than calling, like Ahmadinejad and Chavez, for the end of the dollar hegemony and US imperialism.1

1. The West should take the Iranian leadership at their word and deal with them based on their declared intention not to use uranium enrichment for the development of nuclear weapons.

2. The West, in turn, should eliminate the Iranian leadership's fears of security regarding a Western intervention for their overthrow.

Action Framework:

(1) All decisions must be based on valid agreements according to international laws. In accordance with Article IV of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, Iran has the right to make full use of nuclear energy for peaceful purposes and enrich uranium.

(2) An agreement on enrichment must be reached between the IAEA and Iran which grants the Iranian side the possibilities of enriching uranium on one hand and carrying out their promise not to strive for atomic weapons on the other hand.

(3) The conclusion of the agreement between the IAEA and Iran should be followed by a reduction in the level of military operational readiness of the USA and the NATO in the Persian Gulf region. The range and modalities of such a reduction should be agreed upon parallel to the negotiations between the IAEA and Iran.

(4) A principled agreement on consolidation of an enduring relationship with the Islamic Republic of Iran. The regulation of conflict on the atomic question should be accompanied with and facilitated by a principled agreement on the consolidation of the relationship with the Islamic Republic of Iran. Such an agreement makes for the building of durable confidence. It is to ground the relation on mutually acceptable rational principles. The Federal Government is requested to initiate such an agreement.

| Die Kriegsgefahr wächst: Das Szenario erinnert an den Irak-Krieg von Bahman Nirumand Die ständigen Mitglieder des UN-Sicherheitsrats hatten sich im Atomstreit mit dem Iran Anfang Oktober geeinigt: Die Entscheidung über verschärfte Sanktionen wird vertagt, bis die Internationale Atomenergiebehörde (IAEO) einen neuen Bericht über das Atomprogramm Irans vorgelegt hat. Aber so viel Geduld wollten die USA nicht aufbringen. Im Alleingang verschärften sie die Wirtschaftssanktionen, stuften die Revolutionsgarden als terroristisch ein und übten zudem Druck aus auf ausländische Banken und Unternehmen, ihre Geschäfte mit dem Iran einzustellen. US-Außenministerin Rice nannte Iran das gefährlichste Land der Welt. Nun legte IAEO-Generalsekretär el-Baradei seinen neuen Bericht vor. In ihm bescheinigte er dem Iran zwar Fortschritte bei der Zusammenarbeit, fügte aber auch hinzu, dass Teheran sich weiterhin weigere, der Forderung des UN-Sicherheitsrats nach Einstellung der Urananreicherung nachzukommen. Nichts Neues also. Iran pocht auf sein Recht, die Atomenergie friedlich zu nutzen. El-Baradei und seine Behörde sollten jedoch noch etwas anderes herausfinden: Hat Iran die Absicht, Nuklearwaffen herzustellen. Darüber konnte der Generalsekretär keine klare Auskunft geben. Nur dies: Vorläufig gehe von Iran keine unmittelbare Gefahr aus, und es gebe Zeit genug, den Streit auf diplomatischem Weg zu lösen. Aus amerikanischer Sicht hätte es dieses Berichts nicht bedurft. Schon im Vorfeld wurde aus Washington verkündet, die Kooperationsbereitschaft Irans reiche nicht aus, Iran müsse die Urananreicherung einstellen, andernfalls würden die Sanktionen verschärft. Sollten diese auch zu keinem Ergebnis führen, stünden andere Optionen offen -- militärische eben. Der Streit wird also weiter eskalieren. Da höchstwahrscheinlich Russland und China weitere Sanktionen nicht mittragen wollen, werden die USA am Sicherheitsrat vorbei ihren Kurs fortsetzen. Haben wir nicht ein ähnliches Szenario vor dem Irakkrieg erlebt? Nur dieses Mal sollen Frankreich und Deutschland auch mit ins Boot geholt werden. | The Danger of War Grows: The Scenario Reminiscent of the Iraq War by Bahman Nirumand The permanent members of the Security Council had agreed on the nuclear controversy over Iran at the beginning of October: the decision over escalation of sanctions is to be postponed until the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) submits a new report on Iran's nuclear program. But the USA did not want to exercise so much patience. Unilaterally, it intensified the economic sanctions, classified the Revolutionary Guards as terrorist, and put more pressure on foreign banks and other enterprises to stop their business with Iran. US Secretary of State Rice called Iran the most dangerous country in the world. Now, IAEA Director General El-Baradei submitted his new report. He certified Iran's progress in cooperation, adding that that Tehran still refuses to comply with the Security Council's demand to cease uranium enrichment. Nothing new in this. Iran hammers on its right to use nuclear energy peacefully. El-Baradei and the IAEA should find out something else, however: whether Iran has the intention to build nuclear weapons. The Director General could not give clear information on this question. This much is certain: there is no immediate danger from Iran, and there is enough time to solve the controversy diplomatically. From the American point of view, this report was irrelevant. Even before the release of the IAEA report, Washington already announced: Iran's willingness to cooperate is not enough -- Iran must stop uranium enrichment, or else the sanctions will be intensified. Should the sanctions fail to yield results, there would be other options, even military ones. The controversy will thus continue to escalate. Since Russia and China most likely do not want to impose further sanctions, the USA will continue its course outside the Security Council. Didn't we experience a similar scenario before the Iraq war? Only this time France and Germany will also be in the same boat. |

SOURCE: GlobeScan and PIPA, "20 Nation Poll Finds Strong Global Consensus: Support for Free Market System, But also More Regulation of Large Companies," 11 January 2006

Requiem

The crucified planet Earth,

should it find a voice

and a sense of irony,

might now well say

of our abuse of it,

"Forgive them, Father,

They know not what they do."

The irony would be

that we know what

we are doing.

When the last living thing

has died on account of us,

how poetical it would be

if Earth could say,

in a voice floating up

perhaps

from the floor

of the Grand Canyon,

"It is done."

People did not like it here.

| Le mystère Hezbollah par Anne-Laure Fournier Un an après la dernière guerre au Liban, le parti Hezbollah reste un mystère. Pour la première fois, son leader, Hassan Nasrallah, a accepté la présence de caméras occidentales au sein de l'organisation et répond, sous haute surveillance, aux questions les plus délicates. En retraçant l'histoire de ce mouvement, ce documentaire exceptionnel donne les clés pour comprendre ce qui se joue dans cette région. Qui sont ces "fous de Dieu" qui ont résisté aux attaques de l'armée israélienne en 2006 ? Des "terroristes" selon Bush, de "dangereux fondamentalistes" d'après l'opinion internationale, ou de simples militants d'obédience islamiste chiite engagés dans la vie démocratique de leur pays pour leurs partisans ? La réalité est sans doute aussi complexe que l'histoire du Hezbollah, un mouvement qui suscite les réactions les plus contrastées dans cette société multiculturelle caractérisée par la coexistence de différents courants religieux. A l'issue de longs mois de négociations, Jean-François Boyer, grand reporter et réalisateur, et Alain Gresh, écrivain et journaliste au Monde diplomatique, ont reçu l'autorisation de filmer les installations du mouvement, de diffuser certaines de ses archives inédites et d'interroger son dirigeant charismatique, Hassan Nasrallah. N'éludant aucune question, celui-ci s'exprime sur ses relations avec le gouvernement libanais, les Palestiniens, l'Iran, la provenance de ses fonds et de ses armes, mais aussi sur sa position vis-à-vis de l'Etat d'Israël, dont le Hezbollah a toujours officiellement nié la légitimité. Au coeur du "parti de Dieu" Formé chez les mollahs iraniens, le leader chiite a conservé des liens très forts avec l'ayatollah Khamenei. Ce qui vaut toujours au mouvement libanais l'accusation d'être le "bras armé de la révolution iranienne". Sur ce point, la réponse de Nasrallah est pour le moins ambiguë : "Donnez-moi un seul exemple en vingt-cinq ans d'existence où le Hezbollah aurait servi les intérêts de l'Iran contre ceux du Liban ?"... Issu de différents groupes chiites, le Hezbollah a vécu dans l'ombre durant les quinze premières années de son existence. A la fin de la guerre civile, il est le seul autorisé par la Syrie à poursuivre le combat à la frontière israélienne dans le sud du pays. En 1992, Nasrallah engage son mouvement dans le processus électoral pour lui donner une légitimité démocratique. En 2007, le Hezbollah forme l'un des grands groupes parlementaires libanais avec quatorze députés. Aujourd'hui, il manifeste, avec le principal parti chrétien, pour un gouvernement d'union nationale. Sur son rôle militaire, la position de Nasrallah est claire : "La question des armes est liée au conflit avec l'ennemi israélien. . . Le Hezbollah ne les a jamais utilisées à l'intérieur du pays. Toutes les élections auxquelles il a pris part montrent vraiment que nous sommes engagés dans le processus électoral et la vie du pays." Dans le sud du Liban, les troupes du Hezbollah, moins visibles mais toujours superarmées, restent prêtes à agir. "Tant que l'armée libanaise est capable de gérer le problème, nous n'intervenons pas. Mais si l'armée libanaise et la Finul n'arrivent pas à le résoudre, alors la résistance entre en action." Le terme résume bien une des principales raisons d'être du Hezbollah : un mouvement libanais de résistance contre Israël. Un objectif que partagent beaucoup d'autres Libanais, à en croire Michel Samaha, numéro deux des chrétiens maronites, alliés du "parti de Dieu". De Beyrouth au sud du Liban, les deux journalistes sont partis à la rencontre des combattants du Hezbollah, objet d'un vrai culte, et de leurs familles mais aussi des représentants des principaux partis politiques du pays et de leurs militants. Leur enquête les a menés également sur les lieux de l'action sociale du Hezbollah -- écoles et hôpitaux financés majoritairement par l'organisation -- ainsi que dans les locaux de la chaîne Al-Manar, la plus regardée au Liban et considérée comme le média du parti. Dans un pays où les tensions sont toujours vives, le Hezbollah montre qu'il demeure un acteur incontournable des forces en présence. Première diffusion : dimanche 15 juillet 2007 à 12:25 (hertzien et TNT). | The Mystery of Hezbollah by Anne-Laure Fournier One year after the last war in Lebanon, Hezbollah remains a mystery. For the first time, its leader, Hassan Nasrallah, accepted the presence of Western cameras inside the organization and answers, under high security, the most delicate questions. By retracing the history of this movement, Le Mystère Hezbollah [The Mystery of Hezbollah], an exceptional documentary, provides the keys to understanding what comes into play in this region. Who are these "fanatics of God" who resisted the Israeli army's attacks in 2006? "Terrorists" according to Bush, "dangerous fundamentalists" according to the international opinion, or simple militants of the Shi'i Islamic persuasion engaged in the democratic life of their country for their supporters? The reality is undoubtedly as complex as the history of Hezbollah, a movement which provokes the most contradictory reactions in this multicultural society characterized by the coexistence of various religious currents. After months-long negotiations, Jean-François Boyer, international journalist and film maker, and Alain Gresh, writer and journalist of Le Monde Diplomatique, received an authorization to film Hezbollah installations, to publish some of its previously unpublished archives, and to question its charismatic leader, Hassan Nasrallah. Not evading any question, Nasrallah himself speaks about not only Hezbollah's relations with the Lebanese government, the Palestinians, Iran, and the source of its funds and weapons, but also its position on the state of Israel, whose legitimacy Hezbollah has always officially denied. At the Heart of the "Party of God" Educated by Iranian clerics, the Shi'i leader has maintained very strong bonds with Ayatollah Khamenei. The accusation of being the "armed hands of the Iranian revolution" always gets applied to the Lebanese movement. On this point, the response of Nasrallah is at the very least ambiguous: "Give me a single example in the twenty-five years of its existence where Hezbollah served the interests of Iran against those of Lebanon.". . . A product of various Shi'i groups, Hezbollah lived in the shadow during the first fifteen years of its existence. At the end of the civil war, it became the only one authorized by Syria to continue armed struggle at the Israeli border in southern Lebanon. In 1992, Nasrallah committed his movement to the electoral process to give it democratic legitimacy. In 2007, Hezbollah is one of the major Lebanese parliamentary factions with its fourteen deputies. Today, it is mobilizing, with the principal Christian party, for a national unity government. On its military role, the position of Nasrallah is clear: "The question of weapons is tied to the conflict with the Israeli enemy. . . . Hezbollah has never used them inside Lebanon. All the elections in which it has taken part really show that we are committed to the electoral process and the life of the nation." In the south of Lebanon, Hezbollah troops, less visible but always well armed, remain ready to act. "As long as the Lebanese army can manage the problem, we do not intervene. But if the Lebanese army and the UNFIL are unable to solve it, then the resistance goes into action." The term well summarizes one of Hezbollah's principal raisons d'être: a Lebanese movement of resistance against Israel. An objective shared by many other Lebanese, if we are to believe Michel Samaha, the number two leader of Maronite Christians, allied with the "Party of God." From Beirut to southern Lebanon, the two journalists traveled to meet not only Hezbollah combatants, the object of a veritable cult worship, and their families but also representatives of the main political parties of Lebanon and their militants. Their investigation equally led them to the scenes of Hezbollah's social action -- schools and hospitals financed mainly by the organization -- as well as the premises of the Al-Manar network, the most watched network in Lebanon, considered to be the Hezbollah media. In a country where tensions are always high, Hezbollah shows that it remains an actor impossible to ignore among the opposing forces. First broadcast: Sunday, 15 July 2007 at 12:25 (network and TNT). |

All this has left him [Hossein Derakhshan] isolated from the community of politically active expatriate Iranians who formerly supported him. Some bloggers have removed links to his blog. Others have actively urged readers to boycott him. Interview requests from western-based Iranian media have dried up, as have invitations to ex-pat events and panel discussions. (Don Butler, "The Blogfather: Times Are Hard for Iran's Online Free-speech Pioneer," Ottawa Citizen, 2 November 2007)That is unfortunate, as Hoder has a great deal of useful information to offer, even to those who disagree with him politically, but his exile from exile is all too predictable. Many in the Iranian diaspora have yet to come to terms with the Islamic Republic, and some Iranian leftists are still waiting for a second Iranian Revolution, which makes them unable to listen to, let alone accept, Hoder's new position on the Islamic Republic: "Iran's Islamic republic is still a very new concept and remains a work in progress, he says. Given the chance, 'the major force that could democratize the region is a successful Islamic republic rather than an oppressive, colonizing United States'" (Butler, 2 November 2007).

VLADIMIR: Well? Shall we go?Even my Persian teacher, who, unlike many secular Iranians, does not dismiss Islam or despise Muslims, once fell for a mirage of the second Iranian Revolution: in 1999, he told his wife, to her dismay, that another revolution was about to happen and that he had to go home to join it. 18 Tir, however, was over within a week.

ESTRAGON: Yes, let's go.

They do not move.

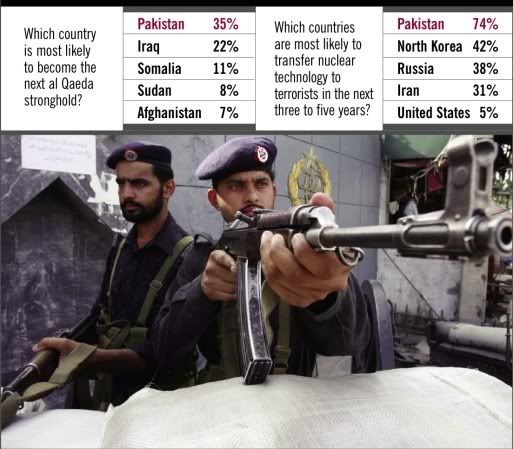

See the complete survey results at foreignpolicy.com/images/TI3_Final_Results.doc.

Now, as the people come out onto the streets and challenge Musharraf's regime, he may resort to using the army to control the cities of the heartland. In the past, the army has balked at being used in such fashion and removed autocratic rulers, both civil and military, and there is evidence of dissatisfaction within its ranks now. Its officers and soldiers have been smarting under the treatment of their colleagues in the frontier region by insurgents. Beheadings and public shaming of captured soldiers and officers by radical insurgents have added to their unhappiness. They battle the faceless and well-armed enemy without personal protective armor and bulletproof vehicles -- and sometimes, according to army insiders, even without adequate boots. (Shuja Nawaz, "In Pakistan, the Army Is Key," Boston Globe, 7 November 2007)Opponents of Musharraf, however, are much less coherent than Iranians who managed to unite long enough to overthrow the Shah. Without a charismatic leadership who can meld contradictory elements of the opposition into a coherent social force capable of establishing a new republic, the end result may very well be either another military coup, which Nawaz all but calls for ("If the state of emergency does not allow Musharraf to control the insurgency or reduce terrorist attacks in Pakistan's cities, the army sadly may become the key to effecting yet another change: to restore the transition to democracy that Musharraf once promised," says he), or a failed state. Pakistan is a perfect nightmare, both for its people and the empire.