Iran has a unique structure of political rule: bureaucratic-collectivist government, in which the Leader balances interests and ambitions of various political factions, which represent different constituencies and are often in open conflict with one another. It's unlike both liberal democracy and state socialism. Quite interesting, actually. I can't think of any other government so factionalized.

What's the main difference among the factions in foreign policy?

Ahmadinejad would rather side with Latin socialists of Cuba, Venezuela, Bolivia, Ecuador, Nicaragua, and so on than with the Western power elites; Rafsanjani, Khatami, Qalibaf, etc. would rather side with the Western power elites than with Latin socialists if only Washington let them. It is difficult to figure out where Ali Khamenei stands.

Reformists, whom many Western liberals and leftists love, think little of Latin socialists: "'Do you really assume people like Chavez (and) Ortega . . . can be Iran's strategic allies?' the reformist daily Etemad-e-Melli said in an editorial Tuesday addressing Ahmadinejad" (emphasis added, Ali Akbar Dareini, "Iran's Discontent With Ahmadinejad Grows," Associated Press, 17 January 2007).

Chavez said to Ahmadinejad: «Es usted uno de los grandes luchadores antimperialistas de esta hora, de este cambio de época que amanece en el horizonte del planeta» (Agencia Bolivariana de Noticias, "Ahmadineyad es uno de los más grandes luchadores antiimperialistas," 27 September 2007). I.e., "You are one of the greatest anti-imperialist fighters today, this time of change of epoch that is dawning on the horizon of the planet."

We do live in interesting times, when Bretton Woods II may be slowly but surely unraveling, indeed a change of epoch, though not of mode of production.

The question is whether the Iranian people think like Chavez or the combined factions of reformists, Rafsanjaniasts, and technocratic neo-conservatives. If most of them think like the former, Iran will be a key nation for Non-Alignment of the 21st Century; if they think like the latter, Iran will be just another nation in the global South.

Sunday, September 30, 2007

Saturday, September 29, 2007

Cacophony on the Left

The US power elite are united on the points that Iran is developing nuclear weapons, is out to destroy Israel, supports "terrorist organizations" abroad, and is killing US troops in Iraq and Afghanistan, and that therefore it must be stopped. They repeat these points over and over and over again, and they are beginning to stick. No one in the audience, presumably educated people, laughed when Columbia University President Lee Bollinger, a liberal man, hammered on them as if they were well established facts.

Leftists, in contrast, have no such unity.

How many opinions exist on the Left regarding Iran's nuclear program alone?

Leftists, in contrast, have no such unity.

How many opinions exist on the Left regarding Iran's nuclear program alone?

- "[C]ountries like Iran should possess nuclear arms to constrain the global hegemony of the United States." -- Slavoj Zizek

- "[U]nambiguously oppose any nuclear energy development in Iran." -- Reza Fiyouzat

- Iran's nuclear energy program makes economic sense, and "[a]s long as the IAEA has not found Iran in violation of its international obligations towards nuclear weapons, the global community must not give in to unreasonable pressure by those nations that use international treaties as tools to advance their and their allies' agenda." -- Muhammad Sahimi

- "We believe that the way out of the current crisis passes through transparency of all the decisions made and actions taken towards achieving nuclear technology, winning the trust of the International Atomic Energy Agency with respect to the extent and goals of advanced industries in Iran, avoiding any provocative statements and actions towards the countries of the region, and planning the foreign policy of the country based on the acceptable and established principles of international policy." -- Tudeh

- "Countries don't get nuclear weapons to use them. They get them to strengthen their bargaining power, and to protect themselves from others. . . . Nuclear weapons are better relegated to the scrapheap of history, to be sure. The world would be a better place without them. There is no guarantee that they will not be launched, perhaps accidentally. But the potential that Iran will build them, and after that the possibility that it might use them, provide no reason to go to war against Iran." -- John B. Quigley

Humanitarian Imperialism

Phil Gasper, a professor of philosophy, notes:

The same day that Ahmadinejad spoke at Columbia, so did Berdimuhammedow, President of Turkmenistan, an event that received zero coverage in the mainstream media. Turkmenistan is a one-party state with a human rights record that makes Iran look like almost a liberal democracy by comparison. But Turkmesistan is also a US ally, so Bollinger remained silent in this case.Selectively highlighting and exaggerating human rights violations in Iran while ignoring or downplaying comparable or even far worse cases committed by US allies and the USA itself is, of course, designed to soften up liberals and leftists for humanitarian imperialism. This strategy worked for Yugoslavia. Will it work for Iran?

Non-Alignment in the 21st Century

Whether or not Iran can resist the US-led multinational empire depends a lot on whether it can gain and keep allies -- Cuba, Venezuela, Bolivia, Nicaragua, and so on -- and get other countries that are neither full members of the empire nor allies of Iran -- Russia, China, India, Turkey, etc. -- to resist economic and other sanctions on Iran as much as possible.1

Iran should also continue to work on driving wedges between the USA on one hand and Japan and European states on the other hand, so the latter won't fully sign on to the US campaign to economically isolate Iran.

Conversely, the fall of Iran would embolden the empire and make it easier for it to intensify attacks on Cuba, Venezuela, Bolivia, Nicaragua, and others. Survival of Iran would weaken US hegemony further, a favorable outcome for all who are or may become Washington's targets.2

Condoleezza Rice claims that Non-Alignment "has lost its meaning":

1 InternetActivist.org has created a useful list of where other nations stand in their relations to Iran and the US campaign to isolate it: "So How Have the US/Israeli Efforts to Isolate Iran Fared around the World?" (27 September 2007).

2 Those leftists who try to isolate Iran from Latin socialist leaders are silly sectarians who have no mass following on the ground and care little about what will become of the Iranian people. The "Iranian Revolutionary Socialists' League," which says it is "highly critical of the Chavez government's extraordinarily close and fraternal relations with the Islamic Republic of Iran" in its open letter (17 September 2006), is a case in point.

Iran should also continue to work on driving wedges between the USA on one hand and Japan and European states on the other hand, so the latter won't fully sign on to the US campaign to economically isolate Iran.

Conversely, the fall of Iran would embolden the empire and make it easier for it to intensify attacks on Cuba, Venezuela, Bolivia, Nicaragua, and others. Survival of Iran would weaken US hegemony further, a favorable outcome for all who are or may become Washington's targets.2

Condoleezza Rice claims that Non-Alignment "has lost its meaning":

. . . I know that there are some who still talk about non-alignment in foreign policy. But maybe that made sense during the Cold War when the world really was divided into rival camps. Now the question that I would ask is, as fellow democracies with so many interests and principles in common at a time when people of every culture, every race, and every religion are embracing political and economic liberty, what is the meaning of non-alignment?Not true. Non-Alignment in the 21st Century means non-alignment with the US power elite, consciously building new military alliances (away from the NATO and other multilateral and bilateral military cooperation with the USA), financial networks (away from the dollar), cultural connections (away from the American media), and so on to roll back the empire.

It has lost its meaning. (Condoleezza Rice, "Remarks at the U.S.-India Business Council 32nd Anniversary 'Global India' Summit," U.S. Chamber of Commerce, Washington, DC, 27 June 2007)

1 InternetActivist.org has created a useful list of where other nations stand in their relations to Iran and the US campaign to isolate it: "So How Have the US/Israeli Efforts to Isolate Iran Fared around the World?" (27 September 2007).

2 Those leftists who try to isolate Iran from Latin socialist leaders are silly sectarians who have no mass following on the ground and care little about what will become of the Iranian people. The "Iranian Revolutionary Socialists' League," which says it is "highly critical of the Chavez government's extraordinarily close and fraternal relations with the Islamic Republic of Iran" in its open letter (17 September 2006), is a case in point.

Thursday, September 27, 2007

Who Wants "a War of Ideas on Homosexuality in the Muslim World"?

Having seen Columbia University President Lee Bollinger, et al. interrogate the President of Iran about homosexuality in Iran, Maureen Dowd observes: "Given the repressive and confused stance of some of our Middle East allies on women and gays, isn’t it insane to get into a war of ideas on homosexuality in the Muslim world?" ("'Fruitbat' at Bat," New York Times, 26 September 2007). That's an understatement, since the most important assets of the empire in the Middle East are the Gulf states, but still a good point. Besides, who can believe that the empire's media, NGOs, intellectuals, etc. recommending the virtue of same-sex love will help make it more popular than it is among peoples who resent their countries being subjected to or attacked by the very same empire? The best one can hope for, figuratively speaking, is that people will just shoot the messenger without shooting the message.

Wednesday, September 26, 2007

Class and Nation

Marxism used to be the dominant ideology of resistance. Why? Because Marxists often aided, and sometimes led, national liberation movements. That's the main reason -- perhaps the only reason -- for its popularity in the early to mid 20th century.

That is also the reason why Marxism never became very popular in imperial powers themselves, (now integrated into one multinational empire under US leadership), for their peoples never had to look for a powerful political tool that would serve as an effective weapon to counter colonial and neo-colonial subjection.

The political currents on the Left that prioritized local class struggles at the expense of national struggles, such as anarchism, council communism, Trotskyism, and so on, did not find comparable mass support worldwide, for their ideas did not resonate with colonial and neo-colonial subjects fighting against imperial masters.

Will things be different in the 21st century? So far, there is no sign that they will be. The most successful current of leftists in the world today, Hugo Chavez and his supporters, are anti-imperialist patriots first and foremost.

Historical materialists can make contributions to humanity to the extent that we make ourselves useful to people in the global South, religious or secular, struggling for republican democracy against US hegemony, seeking to advance the interests of working people in and through national struggle.

That is also the reason why Marxism never became very popular in imperial powers themselves, (now integrated into one multinational empire under US leadership), for their peoples never had to look for a powerful political tool that would serve as an effective weapon to counter colonial and neo-colonial subjection.

The political currents on the Left that prioritized local class struggles at the expense of national struggles, such as anarchism, council communism, Trotskyism, and so on, did not find comparable mass support worldwide, for their ideas did not resonate with colonial and neo-colonial subjects fighting against imperial masters.

Will things be different in the 21st century? So far, there is no sign that they will be. The most successful current of leftists in the world today, Hugo Chavez and his supporters, are anti-imperialist patriots first and foremost.

Historical materialists can make contributions to humanity to the extent that we make ourselves useful to people in the global South, religious or secular, struggling for republican democracy against US hegemony, seeking to advance the interests of working people in and through national struggle.

Sexual Reform: History and Strategy

How did people repeal sodomy laws in the USA? The American Civil Liberties Union says that "[m]ost [states] did it as part of a general reform of criminal laws" ("Getting Rid of Sodomy Laws: History and Strategy that Led to the Lawrence Decision," 2006). That should give another idea to those who seek to expand personal rights and freedoms, including those that concern sexual happiness, in Iran and other Third-World nations, in addition to searching for ways to revise laws and customs by reinterpreting indigenous cultural resources: sometimes, reform of X (e.g., treatment of same-sex sex) is more likely to be accepted if it comes as a part of a general reform, rather than singled out for single-issue mobilization.

Tuesday, September 25, 2007

Khomeini on Sodomy

Laws concerning same-sex sex are against certain sexual acts, not against certain categories of persons, in Iran.1 In my opinion, it is in the interest of Iranians to overturn such laws, as they have been in Cuba and South Africa, as well as many countries in the North (though in the USA not until 2003: Lawrence v. Texas). I do not think, however, that one has to subscribe to the idea of sexual orientations to overturn them.

For instance, do you know Khomeini had a hilarious opinion about sodomy?

1 To understand this distinction, see, especially, Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality: An Introduction (New York: Vintage, 1990 [originally published in France in 1976 and translated into English in 1977]). Other useful works on the origins and development of modern discourse of sexuality include John D'Emilio, "Capitalism and Gay Identity," Powers of Desire: The Politics of Sexuality, eds. Ann Snitow, et al. (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1983), pp. 100-113; and Jonathan Ned Katz, The Invention of Heterosexuality (New York: Dutton, 1995). See, also, Yoshie Furuhashi, "Clash of Sexual Civilizations," Critical Montages, 25 September 2007.

For instance, do you know Khomeini had a hilarious opinion about sodomy?

Ayatollah Khomeini's 1947 manual, Risaleh-yi Towzih al-masa'il (Explanation of problems), is a case in point. Article 349 of this book states that "if a person has sex and [his organ] enters [the other person's body] to the point where it is circumcised [corona] or more, whether he enters a woman or a man, from behind or the front, an adult or pre-adult youngster, and even if no semen is secreted, both persons will become ritually polluted (najes)." But ritual impurity can always be cleansed away through the observance of rules stated in the same manual. (Janet Afary and Kevin B. Anderson, Foucault and the Iranian Revolution: Gender and the Seductions of Islamism, University of Chicago Press, p. 159)Iranian men and women might amend the existing laws against sodomy, which, if successfully prosecuted, entails harsh punishments, by reinterpreting this 1947 Khomeini opinion: you may commit sodomy as long as you are mature and clean yourself by ablution after your enjoyment!

1 To understand this distinction, see, especially, Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality: An Introduction (New York: Vintage, 1990 [originally published in France in 1976 and translated into English in 1977]). Other useful works on the origins and development of modern discourse of sexuality include John D'Emilio, "Capitalism and Gay Identity," Powers of Desire: The Politics of Sexuality, eds. Ann Snitow, et al. (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1983), pp. 100-113; and Jonathan Ned Katz, The Invention of Heterosexuality (New York: Dutton, 1995). See, also, Yoshie Furuhashi, "Clash of Sexual Civilizations," Critical Montages, 25 September 2007.

Clash of Sexual Civilizations

Questioned about the state of homosexuals in the Islamic Republic of Iran, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad said at Columbia University: "In Iran, we don't have homosexuals, like in your country. We don't have that in our country. In Iran, we do not have this phenomenon. I don't know who's told you that we have it" ("President Ahmadinejad Delivers Remarks at Columbia University," CQ Transcripts Wire, 24 September 2007). The audience, shocked, responded with boos and laughter.

Now, that's a clash of sexual civilizations! In America, at least the liberal part of America represented by its great universities like Columbia, it is a norm that people define themselves by the gender of their sexual partners -- homosexual, bisexual, or heterosexual -- and that self definition, sexual identity, is a very important part of themselves. In Iran, too, some people, especially younger urbanites, have adopted the aforementioned sexual categories whose origins Michel Foucault traces back to nineteenth-century bourgeois culture of the West.1 But a majority of Iranians, apparently including their President, have not adopted the idea of sexual orientations, nor have much of the rest of the Third World.

Western liberals and leftists know what to think of the North-South economic gap, but they have yet to figure out a way to sensibly handle this North-South sexual gap.

By the way, Jezebel, having laid out a typical American liberal case against the President of Iran (including the sexual question), declares: "he's definitely hotter than Khatemi" ("So Is Ahmadinejad Kind Of Hot?" 24 September 2007).

I doubt that this will help moderate the clash of sexual civilizations, but take it for what it's worth.

1 See, especially, The History of Sexuality: An Introduction (New York: Vintage, 1990 [originally published in France in 1976 and translated into English in 1977]). Other useful works on the origins and development of modern discourse of sexuality include John D'Emilio, "Capitalism and Gay Identity," Powers of Desire: The Politics of Sexuality, eds. Ann Snitow, et al. (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1983), pp. 100-113; and Jonathan Ned Katz, The Invention of Heterosexuality (New York: Dutton, 1995).

Strange as it may seem, historical materialism in the West today, qualified by insights of such theorists as Foucault, may be most useful for understanding the question of sexuality on the international level rather than resisting the interests of the capitalist class advanced by the US-led multinational empire, which Chavistas, populist Islamists, etc. fight far better than Marxists in practice (though not in theory). Western liberals promote their cultural particularism as if it were cultural universalism, positing their culture as the end of humanity and their path as the universal path of development; those who live in the global South and who are not liberals tend toward cultural relativism, often mistaking the creation of capitalist modernity in the West for the timeless essence of the West to be distinguished from the timeless essence of their cultures. Historical materialism differs from both, seeing contingent evolutions of diverse ways of life, now all colored in the ether of the capitalist mode of production to various degrees, which may or may not converge in the future that is still open.

Update

Yoshie Furuhashi, "Khomeini on Sodomy," Critical Montages, 25 September 2007.

Now, that's a clash of sexual civilizations! In America, at least the liberal part of America represented by its great universities like Columbia, it is a norm that people define themselves by the gender of their sexual partners -- homosexual, bisexual, or heterosexual -- and that self definition, sexual identity, is a very important part of themselves. In Iran, too, some people, especially younger urbanites, have adopted the aforementioned sexual categories whose origins Michel Foucault traces back to nineteenth-century bourgeois culture of the West.1 But a majority of Iranians, apparently including their President, have not adopted the idea of sexual orientations, nor have much of the rest of the Third World.

Western liberals and leftists know what to think of the North-South economic gap, but they have yet to figure out a way to sensibly handle this North-South sexual gap.

By the way, Jezebel, having laid out a typical American liberal case against the President of Iran (including the sexual question), declares: "he's definitely hotter than Khatemi" ("So Is Ahmadinejad Kind Of Hot?" 24 September 2007).

I doubt that this will help moderate the clash of sexual civilizations, but take it for what it's worth.

1 See, especially, The History of Sexuality: An Introduction (New York: Vintage, 1990 [originally published in France in 1976 and translated into English in 1977]). Other useful works on the origins and development of modern discourse of sexuality include John D'Emilio, "Capitalism and Gay Identity," Powers of Desire: The Politics of Sexuality, eds. Ann Snitow, et al. (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1983), pp. 100-113; and Jonathan Ned Katz, The Invention of Heterosexuality (New York: Dutton, 1995).

Strange as it may seem, historical materialism in the West today, qualified by insights of such theorists as Foucault, may be most useful for understanding the question of sexuality on the international level rather than resisting the interests of the capitalist class advanced by the US-led multinational empire, which Chavistas, populist Islamists, etc. fight far better than Marxists in practice (though not in theory). Western liberals promote their cultural particularism as if it were cultural universalism, positing their culture as the end of humanity and their path as the universal path of development; those who live in the global South and who are not liberals tend toward cultural relativism, often mistaking the creation of capitalist modernity in the West for the timeless essence of the West to be distinguished from the timeless essence of their cultures. Historical materialism differs from both, seeing contingent evolutions of diverse ways of life, now all colored in the ether of the capitalist mode of production to various degrees, which may or may not converge in the future that is still open.

Update

Yoshie Furuhashi, "Khomeini on Sodomy," Critical Montages, 25 September 2007.

Ahmadinejad Hailed in Middle East

Washington has sought to pit Sunnis against Shi'is. Its efforts have been augmented by those of sectarian ideologues, secular or religious, in the Middle East. But the pan-Islamist Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, vilified as "Arab-parast" (Arab-worshipper) by Persian-chauvinist Iranian exiles, helps Iran overcome the sectarian division in a way that Iran-First members of Iran's power elite never can. He represents the polar opposite of typical Arab states today, "taking a stand against Israel and the West":

Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, a flinty populist in a zip-up jacket whose scathing rhetoric and defiance of Washington are often caricatured in the Western media, has transcended national and religious divides to become a folk hero across the Middle East.Good for Iranians, good for Arabs, and good for the rest of us opposed to US hegemony.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

"I like him a lot," said Mahmoud Ali, a medical student in Cairo. "He's trying to protect himself and his nation from the dangers around him. He makes me feel proud. He's a symbol of Islam. He seems the only person capable of taking a stand against Israel and the West. Unfortunately, Egypt has gotten too comfortable with Washington."

Ahmadinejad's appeal is especially strong in Egypt, where he is compared to the late President Gamal Abdel Nasser, whose bold, yet doomed vision of pan-Arabism in the 1950s was also aimed at stemming Western influence. In the minds of many Egyptians, Iran's quest to expand its nuclear program despite United Nations sanctions is similar to Nasser's confrontation with the British and French over nationalizing the Suez Canal.

What's striking in Ahmadinejad's case, however, is that the leader of a non-Arab Shiite nation has ingratiated himself with the Middle East's predominantly Sunni Arab population.

In praising the Iranian president, Arabs quickly navigate around historical religious animosities and present-day fears that Iran is undermining Sunnis in Iraq and elsewhere. They prefer to speak of how Ahmadinejad is a rallying voice for Islam at a time the region is bewildered by its powerlessness to fix Iraq, Lebanon and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

"He's a brave man," said Tayseer Ibrahim, an employee of the Egyptian Education Ministry, who was hurrying toward the subway the other day. "He's standing up to the U.S. He could have been intimidated after what happened to Saddam Hussein in Iraq, but he's not. The Iranian people must love him a lot. Hopefully, our Arab leaders will see that you can defy the West and nothing will happen to you."

Munther Farrah, who sells nuts and chocolates in Amman, the Jordanian capital, said he and other Sunnis are troubled by Iran's Shiite theocracy. "But Ahmadinejad is still liked," he said. "We are with him as long as he's against Israel and the U.S."

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

The static of threats and counter-threats has enhanced Ahmadinejad's brand of populism, which stands in vivid contrast to the detached styles of Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak, King Abdullah II of Jordan and King Abdullah of Saudi Arabia. All three U.S. allies regard Iran as a dangerous enemy, most notably over Tehran's support of the militant groups Hezbollah in Lebanon and Hamas in the Gaza Strip. But they have also borrowed a bit from Ahmadinejad's script by criticizing Bush administration policies and the bloodshed in Iraq.

The governments in Egypt, Jordan and Saudi Arabia have undercut media freedom and suppressed political dissent, and are viewed by some of their people as corrupt and ineffectual in addressing economic and social problems. Iran runs its own version of the omnipresent, repressive state, but Ahmadinejad's intense distrust of the U.S. and hatred of Israel have elevated him to mythical status for the frustrated Arab mechanic, taxi driver or lawyer seeking a pure, forceful message.

The sentiment is similar to the respect won by Hezbollah, which fought a war with Israel in 2006, and Hamas, the radical Palestinian party that seized control of the Gaza Strip in June. Both were credited with tenacity and portrayed as underdogs battling against larger enemies. This type of resolve, along with Iran's pride as a sovereign state, echoes through Ahmadinejad's speeches and asides.

"It is more of a scream that reflects the incapacity of both the Arab regimes and Arab peoples to achieve anything on the regional level," said Nabil Abdel Fattah, a political analyst with Al Ahram Center for Political and Strategic Studies in Cairo.

Ahmed Taher, an Egyptian doctor, credits Ahmadinejad for pursuing nuclear technology, which Tehran says is for civilian use, but the U.S. suspects is for weapons.

"It's beyond doubt that Ahmadinejad's popularity surpasses any other leader in the Middle East," Taher said. "We shouldn't blame him for seeking nuclear weapons. Israel has them. It will be more balance for Muslims if we have them too. Israel is much more dangerous to the world than Ahmadinejad." (Jeffrey Fleishman, "Ahmadinejad Hailed in Middle East," Los Angeles Times, 24 September 2007)

Monday, September 24, 2007

Dilbert on Ahmadinejad

Scott Adams, the Dilbert cartoonist, satirizes the American Right's attitude toward the President of Iran:

1 See, for instance, this new study of young Jewish Americans' opinions about Israel:

I was happy to hear that NYC didn't allow Iranian President Ahmadinejad to place a wreath at the WTC site. And I was happy that Columbia University is rescinding the offer to let him speak. If you let a guy like that express his views, before long the entire world will want freedom of speech.Very smart. Aside from being a good satirical attack on Washington's media war against Iran, it also is another piece of evidence that Israel is beginning to lose American liberals' support. Good for Palestinians, good for Americans, and good for Jews who are fed up with Zionism.1

I hate Ahmadinejad for all the same reasons you do. For one thing, he said he wants to "wipe Israel off the map." Scholars tell us the correct translation is more along the lines of wanting a change in Israel's government toward something more democratic, with less gerrymandering. What an ass-muncher!

Ahmadinejad also called the holocaust a "myth." Fuck him! A myth is something a society uses to frame their understanding of their world, and act accordingly. It's not as if the world created a whole new country because of holocaust guilt and gives it a free pass no matter what it does. That's Iranian crazy talk. Ahmadinejad can blow me. ("A Feeling I'm Being Had," The Dilbert Blog, 22 September 2007)

1 See, for instance, this new study of young Jewish Americans' opinions about Israel:

Young U.S. non-Orthodox Jews are becoming increasingly lukewarm if not alienated in their support for Israel in a trend that is not likely to be reversed, according to a study released on Thursday.

Blending into U.S. society, including marriage to non-Jews and a tendency to look on Judaism more in religious terms than ethnic ones, is part of what's happening, the study found.

"For our parent's generation, the question that mattered was, how do we regard Israel? For Generation Y (born after 1976) the question is indeed, why should we regard Israel?" said Roger Bennett, a vice president of The Andrea and Charles Bronfman Philanthropies, which sponsored the study.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

But the study found that "feelings of attachment may well be changing as warmth gives way to indifference, and indifference gives way even to downright alienation."

The study found only 48 percent of U.S. Jews under age 35 believe that Israel's destruction would be a personal tragedy for them, compared to 77 percent of those 65 and older.

In addition, only 54 percent of those under the age of 35 are "comfortable with the idea of a Jewish State" as opposed to 81 percent of those 65 and older. (Michael Conlon, "Study Finds U.S. Jews Distance Selves from Israel," Reuters, 6 September 2007)

After Eschatology

When Marxism was the dominant ideology of resistance to capitalism and imperialism, it had a grand narrative of history, a cousin of the Christian narrative, in which "the last shall be first, and the first last: for many be called, but few chosen" (Matt. 20:16), a narrative whose protagonist is the proletarian vanguard inspired by an eschatological vision.

Then, many Marxists, for good and bad reasons, had a crisis of faith, the crisis of which Khomeini took note, and they turned to a new myth, the myth of Western Liberal Democracy as the End of History, the myth of which Francis Fukuyama is the best known narrator. In short, they became liberals, whether or not they knew that they did.

Historical materialism as a social theory has become better, having shed the myth of the End of History; and yet, it has fewer adherents than before, and many of the remaining adherents are intellectuals who are not in a position to lead workers and farmers, estranged from them by income, education, secularism, and other dividers. Historical materialists must find a way to overcome this estrangement.

Then, many Marxists, for good and bad reasons, had a crisis of faith, the crisis of which Khomeini took note, and they turned to a new myth, the myth of Western Liberal Democracy as the End of History, the myth of which Francis Fukuyama is the best known narrator. In short, they became liberals, whether or not they knew that they did.

Historical materialism as a social theory has become better, having shed the myth of the End of History; and yet, it has fewer adherents than before, and many of the remaining adherents are intellectuals who are not in a position to lead workers and farmers, estranged from them by income, education, secularism, and other dividers. Historical materialists must find a way to overcome this estrangement.

Queering Freedom House

Arsham Parsi, Executive Director of the IRanian Queer Organization (IRQO, formerly Persian Gay & Lesbian Organization [PGLO]), thanks Gozaar: "To begin with, I would like to thank Gozaar -- A Journal on Democracy and Human Rights in Iran -- and its editor Sasan Ghahreman for inviting the Iranian Queer Organization (IRQO) here today so we could be with you" ("Arsham Parsi Speaks at Gozar Panel, Silenced Voices, Toronto," IRQO.net, 16 September 2007).

Scrawl down to the bottom of Gozaar's homepage, and you'll see that it unabashedly features the logo of its sponsor Freedom House.1 Getting associated with Freedom House, an organization that is among the best known elements of Washington's regime change campaign in Iran, is the surest way to turn all thinking Iranians against your organization and set back your cause.2 Evidently, for Parsi and IRQO, welfare of the constituency he claims to represent, GLBTQ individuals in Iran, is far less important than serving the empire.

Funding for this project of Freedom House is "provided mainly by The Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs, under its Human Rights and Democracy programs," says Gozaar. As the empire is multinational, so is its regime change campaign, but this is an aspect of imperialism that leftists have yet to investigate in depth.

1 What is Freedom House?

Scrawl down to the bottom of Gozaar's homepage, and you'll see that it unabashedly features the logo of its sponsor Freedom House.1 Getting associated with Freedom House, an organization that is among the best known elements of Washington's regime change campaign in Iran, is the surest way to turn all thinking Iranians against your organization and set back your cause.2 Evidently, for Parsi and IRQO, welfare of the constituency he claims to represent, GLBTQ individuals in Iran, is far less important than serving the empire.

Funding for this project of Freedom House is "provided mainly by The Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs, under its Human Rights and Democracy programs," says Gozaar. As the empire is multinational, so is its regime change campaign, but this is an aspect of imperialism that leftists have yet to investigate in depth.

1 What is Freedom House?

While touting itself as having a "bipartisan character," Freedom House is often associated with hawkish and neoconservative factions within both major U.S. parties, a fact made clear by many of its current and past supporters and board members, which have included former CIA Director James Woolsey, ex-Reagan administration official Kenneth Adelman, the late UN Amb. Jeane Kirkpatrick, and former member of the Committee on the Present Danger, Max Kampelman. Other board members have included the conservative Rolling Stone writer P.J. O'Rourke; Samuel Huntington, a Harvard professor who says the post-Cold War period will be dominated by a "clash of civilizations" between the Muslim and Christian worlds; Ruth Wedgwood, a right-leaning human rights lawyer; and Arthur Waldron, a longtime foreign policy hawk who has been a leading advocate for a hardline China policy. Many of these individuals have also supported the work of a number of other conservative organizations, including the Project for the New American Century, the Center for Security Policy, and the American Enterprise Institute. Other Freedom House supporters and scholars have included Mark Falcoff, the late Penn Kemble, Nina Shea, and Daniel Pipes. ("Freedom House," Right Web, 26 July 2007)What is it doing in Iran?

In choosing Freedom House as the venue for a foreign policy address this week, President George W. Bush has stepped into an intense debate among democracy activists in the US and Iran on how US dollars should be used to carry out the administration's policy of promoting freedom in the Islamic republic.2 On a related issue of how Gozaar damaged the "One Million Signatures" campaign, see Hossein Derakhshan, "Beware Gozaar," Editor: Myself, 26 January 2007.

Few in the Washington audience on Wednesday realised that Freedom House, an independent institution founded more than 60 years ago by Eleanor Roosevelt, the former first lady, is one of several organisations selected by the State Department to receive funding for clandestine activities inside Iran.

Peter Ackerman, chairman of the board of trustees, who introduced Mr Bush, is also the founder of a separate organisation that promotes non-violent civic disobedience as a form of resistance to repressive regimes. His International Center on Non-Violent Conflict has organised discreet "workshops" in the Gulf emirate of Dubai to teach Iranians the lessons learned from east European movements.

A separate organisation, the Iran Human Rights Documentation Centre based in New Haven, Connecticut, has also received US funding and organised a Dubai "workshop" for Iranians last year that was not made public.

Mr Ackerman, who is very wealthy from an earlier career as a financier, says he does not accept government money. Questioned by the FT, Freedom House confirmed it had received funding from the State Department for activities in Iran. It declined to give details but said it was not involved in Mr Ackerman's work in Dubai.

Freedom House also disclosed that it received $100,000 (€83,873, £57,500) from Mr Ackerman last year and a further $100,000 from his organisation.

In a research study, with Mr Ackerman acting as chief adviser, Freedom House sets out its conclusions: "Far more often than is generally understood, the change agent is broad-based, non-violent civic resistance - which employs tactics such as boycotts, mass protests, blockades, strikes and civil disobedience to de-legitimate authoritarian rulers and erode their sources of support, including the loyalty of their armed defenders." (Guy Dinmore, "Bush Enters Iran 'Freedom' Debate," Financial Times, 31 March 2006)

Sunday, September 23, 2007

Muhajababes

There is a pop-cultural book about pop culture in the predominantly Islamic world: Muhajababes by Allegra Stratton.1 The book explores the intersection of secular and religious trends and fashions. A number of Muslims, especially bourgeois and petit-bourgeois, have amalgamated Islam with consumerism.

That is a tendency of which Nawal El Saadawi,2 for example, has been a long-standing critic. In a way, the kind of secular, class-conscious, anti-imperialist feminism (which came before the third-wave era of "power feminism," "sex-positive feminism," and "lipstick lesbianism") that Saadawi and others of her generation represent is far more ascetic than the worldview of those who combine consumerism with religion (even religious fundamentalism), and at present this old-fashioned brand of secular feminism has no chance of catching on, either in the Middle East or outside it.

Secular leftists in general, due to their ideological marginality and confinement to relatively privileged classes and strata (about which Saadawi is also very critical), are no match for consumerist Islam that is ironically backed by Saudi capital. If any ideology challenges consumerist Muslims at all, it is not a secular left-wing ideology but the populist, anti-imperialist Islam of Hamas, Hizballah, and other forces like them.

1 Here is a useful review of Muhajababes:

That is a tendency of which Nawal El Saadawi,2 for example, has been a long-standing critic. In a way, the kind of secular, class-conscious, anti-imperialist feminism (which came before the third-wave era of "power feminism," "sex-positive feminism," and "lipstick lesbianism") that Saadawi and others of her generation represent is far more ascetic than the worldview of those who combine consumerism with religion (even religious fundamentalism), and at present this old-fashioned brand of secular feminism has no chance of catching on, either in the Middle East or outside it.

Secular leftists in general, due to their ideological marginality and confinement to relatively privileged classes and strata (about which Saadawi is also very critical), are no match for consumerist Islam that is ironically backed by Saudi capital. If any ideology challenges consumerist Muslims at all, it is not a secular left-wing ideology but the populist, anti-imperialist Islam of Hamas, Hizballah, and other forces like them.

1 Here is a useful review of Muhajababes:

The video-clip girls are indeed a serious cultural force - Nancy Ajram was recently voted 'one of the region's most influential Arabs' by the Arabic version of Newsweek -- but their eminence grise is the Saudi Prince Al-Waleed bin Talal, the eighth-richest man in the world and the owner of the Rotana satellite stations and record label that 80 per cent of Arab pop stars are signed to. Despite the acres of flesh on display at Rotana, the singers' most fervent fans are the eponymous 'muhajababes': veiled girls (muhajaba is Arabic for 'one who veils') who nevertheless wear skin-tight jeans, stiletto heels and plenty of make-up. To describe them, Stratton learns a great new Arabic word, 'rewish', which means somewhere between 'hip' and 'distracted' - these are the Dazed & Confused-sters of the Middle East. Nominally strict Muslims, some sneak cigarettes, date boys and engage in other behaviour that is technically haram (forbidden).2 This interview serves as a good introduction to Saadawi's worldview:

Ranged against (or sometimes, confusingly, alongside) them are the conservative anti-clip brigade. But increasingly they, too, Stratton discovers, worship the TV screen. Their idol is a swoonsome young accountant-turned-preacher called Amr Khaled, who appears on religious shows with 'young men and women, praying, crying and giving hearty, healthy belly laughs, as if they were in a vitamin-supplement advert'. Stratton is particularly scathing about Khaled, a well-fed BMW driver who announces, televangelist-style, that: 'I want to have money and the best clothes to make people love God's religion.' But it's only when she ditches her dream of finding the Arab Bob Dylan and focuses on Khaled's 'Life Makers' initiative that Muhajababes gains in pace and authority.

Capable of mobilising hundreds of thousands of young Muslims worldwide for causes ranging from the benign (collecting clothes for charity) to the sinister (berating smokers and drinkers in public), Khaled is the well-groomed face of a new, media-friendly conservative Islam that reviles the 'degrading display of women's bodies'.

Between the muhajababes and the Life Makers, there is little room for the handful of arty oddballs (including the gay Kuwaiti who provides the book's best line, 'There's no such thing as straight in Kuwait') to whom Stratton, as a liberal Westerner, is instinctively drawn. But this is the point. Social change in the Middle East won't be led, as Stratton -- and many Western policy-makers -- had hoped, by the secular trendies, but by those she dismissively describes as the 'Life Making, green-fingered, litter-collecting, I'd-like-to-teach-the-world-to-sing Arabs'. Muhajababes discovers a world in which religion is packaged and sold as slickly as a video clip. And the people behind the scenes are the same, too: Prince Al-Waleed has already diversified into an immensely popular new Islamic channel, Al-Risala ('The Message'). And it is not a conveniently distant world either: having been banned from preaching by the nervous Egyptian regime in 2002, Khaled now finds refuge in the UK and is soon, Stratton surmises, advising the British government on engaging with the Muslim world.

It is hard, as Muhajababes demonstrates, for secular observers to appreciate the genuine force of belief, however clumsily or confusedly it may be expressed. In the summer of 2004 when I was living in Cairo, I was surprised to meet engineering graduates who believed in djinn with green claws and veiled girls who swapped oral-sex tips. But with bombs falling in the Beirut streets that Stratton scoured fruitlessly for a trendier revolution, the region's latest crisis is a reminder that it's essential to try. (Rachel Aspden, "Islam and the Porno Devils," The Guardian, 23 July 2006)

Women's eNews: How are today's feminists different from your generation of feminists?

Nawal El Saadawi: We don't have feminists any more. Feminism to me is to fight against patriarchy and class and to fight against male domination and class domination. We don't separate between class oppression and patriarchal oppression. Many so-called feminists don't. We can't be liberated under American occupation, for example. The new women are not aware of that.

These days, there is also a phenomenon I call "false awareness." Many women who call themselves feminists today wear makeup, high heels, tight jeans and they still wear the hijab. It is very contradictory. They are victims of both religious fundamentalism and American consumerism. They have no political awareness. They are unaware of the connection between the liberation of women on the one hand and of the economy and country on the other. Many consider only patriarchy as their enemy and ignore corporate capitalism.

Women's eNews: Why have Egyptian feminists and liberal intellectuals failed in capturing the imagination of grassroots Egyptian society and why aren't we seeing an active independent grassroots movement today?

Nawal El Saadawi: The elite secular Marxist and socialist groups were always separated from the peasants and poor people. They were busy looking up to the rulers and gave their backs to the people. They were speaking all the time on behalf of the masses only to achieve political aims.

Sadat put me in prison along with some other men. Under Mubarak, I've been "gray-listed." Although there is no official order banning me, I can't appear in the national media--it's an unwritten rule. There is no chance for people like me to be heard by the people.

Even the nongovernmental organizations are controlled by the government. When I was at Mumbai recently at the World Social Forum, they were calling them "Go-En-Ghee-Ohs," or government NGOs. Most of the NGO's in Egypt are co-opted by the government. There is no real opposition party that represents the people's interests either. Even the Tagammu', the so-called leftist political party, was created by Sadat along with all the other official parties. All the party leaders cooperate with the government. (Ahmed Nassef, "Egypt's Leading Feminist Unveils Her Thoughts," Women's eNews, 25 February 2004)

Saturday, September 22, 2007

Bipartisan Consensus on Israel

Fox News has already lined up Columbia students to speak about their school's invitation to the President of Iran, including the presidents of the College Democrats and Republicans, Josh Lipsky and Chris Kulawik: "The Fox Lineup," Bwog, 21 September 2006.

I looked up Lipsky and Kulawik to learn about their foreign policy views and found that both are united against Norman G. Finkelstein, accusing him of "support of terrorism": Chris Kulawik and Josh Lipsky, "Hate Comes to Columbia," Columbia Spectator, 1 March 2006.

That is a good indicator of their position on Washington's Iran campaign, no matter what they think of Columbia's right to invite President Ahmadinejad, and suggests the depth of bipartisan consensus on Israel in particular and the Middle East in general, reaching all the way down to future party operatives.

I looked up Lipsky and Kulawik to learn about their foreign policy views and found that both are united against Norman G. Finkelstein, accusing him of "support of terrorism": Chris Kulawik and Josh Lipsky, "Hate Comes to Columbia," Columbia Spectator, 1 March 2006.

That is a good indicator of their position on Washington's Iran campaign, no matter what they think of Columbia's right to invite President Ahmadinejad, and suggests the depth of bipartisan consensus on Israel in particular and the Middle East in general, reaching all the way down to future party operatives.

Open Letter to Progressive Opponents of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad

The President of Iran is invited to speak at Columbia on Monday. Student organizations, as well as assorted right-wingers, are planning to protest. The Columbia Coalition Against the War, however, has wisely decided not to join them and instead published an "Open Letter to Progressive Opponents of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad," arguing that

There are other means for engagement with Iran than war, and other means for disagreement with Ahmadinejad than the planned protest. We call on those who do not support a war with Iran to be wary of the vilification of Ahmadinejad, to avoid Monday's rally, and to express vocally their opposition to military intervention.A timely intervention.

Friday, September 21, 2007

Inflation: Iran and Venezuela

Endless economic propaganda against populism is the order of the day, especially when it comes to Iran. A case in point is Robert Tait's latest article in the Guardian1:

Iran's Central Bank calculates that inflation stands at 17.1% now ("Summary Results of the Consumer Price Index in Urban Areas in Iran," 22 June - 22 July 2007), which is just about the post-revolution average. The IMF estimates it to be 17.8% in 2007, projected to decline to 15.8% in 2008.

It's basically the same domestic policy of low interest rates as Venezuela's, and the same global economic trends, that are adding to the price pressures in Iran, and the same policy of large subsidies as Venezuela's also cushions inflation's impacts on the poor in Iran, despite economists, technocrats, and journalists speaking in the name of the poor but actually rooting for neoliberal solutions -- namely raising interest rates and cutting subsidies for the poor.

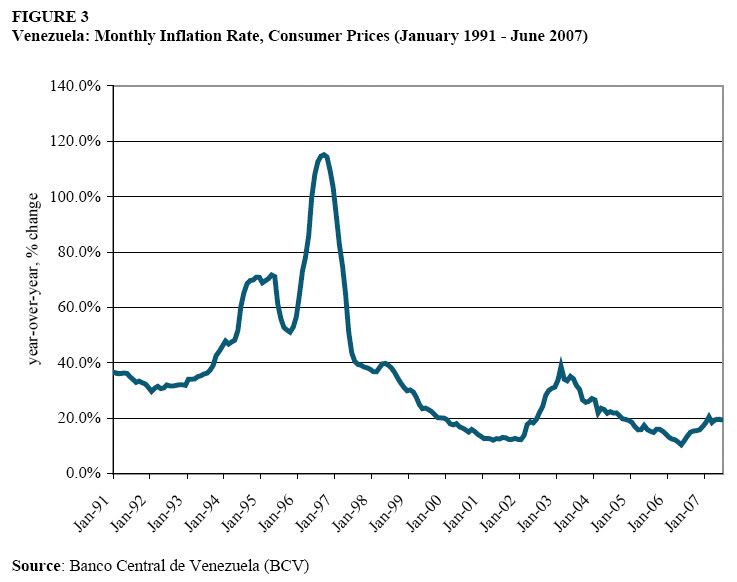

Mark Weisbrot and Luis Sandoval write in "The Venezuelan Economy in the Chávez Years" (July 2007) that "[r]eal interest rates have been negative throughout the recovery as measured by the 90-day deposit rate or most of the recovery, as measured by the lending rate" (p. 17). Pushed also by expansive fiscal policy, Venezuela's inflation, currently running at 19.4 percent, exceeds the government's target. But they also note that "it should be emphasized that double-digit inflation rates in a developing country such as Venezuela are not comparable to the same phenomenon occurring in the United States or Europe," pointing out that Venezuela experienced far worse inflation in the 1990s (p. 2).

The same can be said about Iran.

Why have Weisbrot and Sandoval made efforts to clarify the economic history of Venezuela? Because they know that journalism heightening economic anxieties, which in turn will have negative impacts on real economy, is part of the ruling class propaganda that needs to be countered.2

Leftists ought to be doing the same about Iran's economy, but they don't. Rather, most of them do the opposite, apparently having convinced themselves that any economic propaganda against the "Iranian regime" is in the interest of Iran's working class, which isn't true. All that propaganda against populism does is to help Iran's ruling class push for neoliberal economics and help Washington in its campaign to economically isolate Iran.

1 One learns that Tait has an agenda of promoting Rafsanjani, which in part explains how he reports on Iran's economy and domestic faction fights: Hossein Derakhshan, "Robert Tait Markets Rafsanjani to Americans," Editor: Myself, 21 August 2007.

2 They know their history: "Predictions of economic collapse under Allende were replayed in CIA-generated articles in European and Latin American newspapers" (Church Report, "Covert Action in Chile 1963-1973," 18 December 1975). But nowadays the hegemony of neoliberal economics is such that the CIA doesn't even need to plant a story. The media do it all on their own.

The Islamic Revolution Devotees Society -- a fundamentalist grouping of revolutionary veterans co-founded by Mr Ahmadinejad -- has added its voice to a rising chorus of economic discontent by warning the president that spiralling living costs are hurting the poor and undermining his stated goal of social justice.The rift, however, is no news. The Islamic Revolution Devotees Society (Jamiyat-e Isargaran-e Inqilab-e Islami), the group most of whose members' views are not fundamentalist in any recognizable sense but, if anything, technocratic, didn't back Ahmadinejad in the first round of the 2005 presidential elections, endorsing Mohammad Baqer Qalibaf instead:

The society says the government is to blame because it embarked on extravagant projects while failing to control the money supply. . . .

The latest report implicitly criticises his contemptuous view of economics by describing it as a "specialised science" and says Iran's inflationary problems cannot be solved by "ad hoc decisions". That may partly refer to one of Mr Ahmadinejad's most controversial recent moves in which he ordered banks to cut interest rates to 12% - below inflation, which is estimated at between 20% and 30%. ("Party Turns on Ahmadinejad over Attitude to Inflation," 20 September 2007)

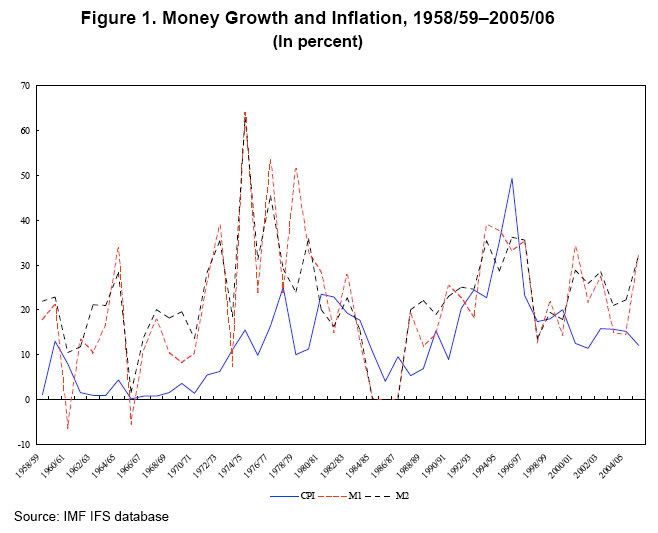

Neither is the current level of inflation -- which Tait exaggerates, citing no sources -- new in Iran, which has seen much worse. According to none other than the International Monetary Fund:

- The Isargaran eventually backed the candidacy of national police chief and former Revolutionary Guard Mohammad Baqer Qalibaf, announcing that he won out over Ahmadinejad, Larijani, Ali-Akbar Velayati, Mohsen Rezai, and Ahmad Tavakoli, 'Siyasat-i Ruz' reported on 30 May. (Bill Samil, "Iran: A Rising Star In Party Politics," Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, 7 November 2005)

- The Devotees Society held its third congress in early March, but Ahmadinejad was in Malaysia at the time. But 'Sharq' suggested on March 4 that the president's absence could be traced to the society's failure to support him in the first round of the June 2005 election in favor of Mohammad Baqer Qalibaf. (Bill Samil, "Analysis: Rivalries Heat Up Among Iran's Conservatives," Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, 25 April 2006)

Iran has a history of relatively high inflation, with CPI inflation averaging more than 17 percent since the 1979 revolution. . . . The 1979 revolution clearly represents a breaking point in the money-inflation relationship. Inflation increased significantly following the revolution (from 6.6 percent to 17.4 percent on average), but the acceleration in money growth was almost negligible (from 23.8 percent to 24.6 percent on average). After the dramatic increase experienced in the mid-1990s, when it reached a peak of 50 percent, inflation declined up until the first quarter of 2006/07, though the annual average remained in the double digits. (Leo Bonato, "Money and Inflation in the Islamic Republic of Iran," IMF Working Paper, May 2007, p. 3-5)See, also, "Figure 1. Money Growth and Inflation, 1958/59-2005/06" on page 4 of the same paper.

Iran's Central Bank calculates that inflation stands at 17.1% now ("Summary Results of the Consumer Price Index in Urban Areas in Iran," 22 June - 22 July 2007), which is just about the post-revolution average. The IMF estimates it to be 17.8% in 2007, projected to decline to 15.8% in 2008.

It's basically the same domestic policy of low interest rates as Venezuela's, and the same global economic trends, that are adding to the price pressures in Iran, and the same policy of large subsidies as Venezuela's also cushions inflation's impacts on the poor in Iran, despite economists, technocrats, and journalists speaking in the name of the poor but actually rooting for neoliberal solutions -- namely raising interest rates and cutting subsidies for the poor.

Mark Weisbrot and Luis Sandoval write in "The Venezuelan Economy in the Chávez Years" (July 2007) that "[r]eal interest rates have been negative throughout the recovery as measured by the 90-day deposit rate or most of the recovery, as measured by the lending rate" (p. 17). Pushed also by expansive fiscal policy, Venezuela's inflation, currently running at 19.4 percent, exceeds the government's target. But they also note that "it should be emphasized that double-digit inflation rates in a developing country such as Venezuela are not comparable to the same phenomenon occurring in the United States or Europe," pointing out that Venezuela experienced far worse inflation in the 1990s (p. 2).

The same can be said about Iran.

Why have Weisbrot and Sandoval made efforts to clarify the economic history of Venezuela? Because they know that journalism heightening economic anxieties, which in turn will have negative impacts on real economy, is part of the ruling class propaganda that needs to be countered.2

Leftists ought to be doing the same about Iran's economy, but they don't. Rather, most of them do the opposite, apparently having convinced themselves that any economic propaganda against the "Iranian regime" is in the interest of Iran's working class, which isn't true. All that propaganda against populism does is to help Iran's ruling class push for neoliberal economics and help Washington in its campaign to economically isolate Iran.

1 One learns that Tait has an agenda of promoting Rafsanjani, which in part explains how he reports on Iran's economy and domestic faction fights: Hossein Derakhshan, "Robert Tait Markets Rafsanjani to Americans," Editor: Myself, 21 August 2007.

2 They know their history: "Predictions of economic collapse under Allende were replayed in CIA-generated articles in European and Latin American newspapers" (Church Report, "Covert Action in Chile 1963-1973," 18 December 1975). But nowadays the hegemony of neoliberal economics is such that the CIA doesn't even need to plant a story. The media do it all on their own.

Empire's Best Weapon

The empire's media gleefully report on Hamas's trouble in Gaza: e.g., Associated Press, "Palestinian Opinion Poll Shows Hamas Trailing Fatah, Criticism of Gaza Takeover," 17 September 2007.

The case of the Hamas government shows that the US-led multinational empire's most effective weapon is political and economic, not military: economically deprive the enemy, financially support collaborators, and wait till the desperate populace begin to desert the enemy and to turn to the collaborators. Coups and other military means, if they become necessary at all, are often mainly just the finishing touch.

This mode of subversion is especially suitable for the enemy who lacks domestic economic resources for independent survival to begin with, as is the case with the Palestinians now and the Haitians before them. (What has happened since the elections that put Hamas in power, by the way, demonstrates that the idea of a "two-state" solution is merely a mirage that obscures the reality of the Jewish state from the sea to the river.) It moreover has a crucial ideological advantage: the empire can pretend that its hands are clean, and its populace either "spontaneously" consent to that pretension or (more typically) remain completely ignorant of what is done and to what effect.

Unlike wars, which considerable numbers of people in the global North may be moved to oppose in the streets, as they did before the invasion of Iraq, there is no tangible opposition in the North to economic sanctions of this or that government in the South.

Whither Hamas? Tel Aviv just declared Gaza a "hostile entity" and decided to "impose sanctions on supplies of electricity, fuel, and other basic goods and services to the civilian population of Gaza" (The Israeli Committee Against House Demolitions, "Gaza: A Call for Urgent Action," 20 September 2007). If pushed against the wall, Hamas may very well (belatedly) decide that entry into electoral politics was an error and go back to armed resistance. Or they may fade into nothingness, leaving the vacuum to be filled by terrorist cells of the al Qaeda variety. Ahmed Yousef, a political advisor to Palestinian Prime Minister Ismail Haniyeh, writes in Ha'aretz: "Hamas is a bulwark in the face of radical and militant ideas and trends. Policies whose aim is the isolation or marginalization of Hamas will not only fail but will also set the stage for the spread of extremist thinking in occupied Palestine" ("Hamas Is the Key," 21 September 2007). I hope for a different outcome, but from here there is nothing I can do to help the Palestinians find it.

The case of the Hamas government shows that the US-led multinational empire's most effective weapon is political and economic, not military: economically deprive the enemy, financially support collaborators, and wait till the desperate populace begin to desert the enemy and to turn to the collaborators. Coups and other military means, if they become necessary at all, are often mainly just the finishing touch.

This mode of subversion is especially suitable for the enemy who lacks domestic economic resources for independent survival to begin with, as is the case with the Palestinians now and the Haitians before them. (What has happened since the elections that put Hamas in power, by the way, demonstrates that the idea of a "two-state" solution is merely a mirage that obscures the reality of the Jewish state from the sea to the river.) It moreover has a crucial ideological advantage: the empire can pretend that its hands are clean, and its populace either "spontaneously" consent to that pretension or (more typically) remain completely ignorant of what is done and to what effect.

Unlike wars, which considerable numbers of people in the global North may be moved to oppose in the streets, as they did before the invasion of Iraq, there is no tangible opposition in the North to economic sanctions of this or that government in the South.

Whither Hamas? Tel Aviv just declared Gaza a "hostile entity" and decided to "impose sanctions on supplies of electricity, fuel, and other basic goods and services to the civilian population of Gaza" (The Israeli Committee Against House Demolitions, "Gaza: A Call for Urgent Action," 20 September 2007). If pushed against the wall, Hamas may very well (belatedly) decide that entry into electoral politics was an error and go back to armed resistance. Or they may fade into nothingness, leaving the vacuum to be filled by terrorist cells of the al Qaeda variety. Ahmed Yousef, a political advisor to Palestinian Prime Minister Ismail Haniyeh, writes in Ha'aretz: "Hamas is a bulwark in the face of radical and militant ideas and trends. Policies whose aim is the isolation or marginalization of Hamas will not only fail but will also set the stage for the spread of extremist thinking in occupied Palestine" ("Hamas Is the Key," 21 September 2007). I hope for a different outcome, but from here there is nothing I can do to help the Palestinians find it.

Wednesday, September 19, 2007

Let the Ascetics Sing of the Garden of Paradise

How do people develop? Dialectically, or so suggest

Ghazals of Ghalib, one of the witnesses to the Great Uprising of 1857.

In Jane Hirshfield's translation (The Enlightened Heart, Ed. Stephen Mitchell, Harper Perennial, 1989):

Ghazals of Ghalib, one of the witnesses to the Great Uprising of 1857.

ستایشگر ہے زاہد اس قدر جس باغِ رضواں کا

وہ اک گلدستہ ہے ہم بے خودوں کے طاقِ نسیاں کا

کیا آئینہ خانے کا وہ نقشہ تیرے جلوے نے

کرے جو پرتوِ خورشید عالم شبنمستاں کا

مری تعمیر میں مضمر ہے اک صورت خرابی کی

ہیولیٰ برقِ خرمن کا ہے خونِ گرم دہقاں کا

خموشی میں نہاں خوں گشتہ لاکھوں آرزوئیں ہیں

چراغِ مردہ ہوں میں بے زباں گورِ غریباں کا

نظر میں ہے ہماری جادۂ راۂ فنا غالب

کہ یہ شیرازہ ہے عالم کے اجزاۓ پریشاں کا

وہ اک گلدستہ ہے ہم بے خودوں کے طاقِ نسیاں کا

کیا آئینہ خانے کا وہ نقشہ تیرے جلوے نے

کرے جو پرتوِ خورشید عالم شبنمستاں کا

مری تعمیر میں مضمر ہے اک صورت خرابی کی

ہیولیٰ برقِ خرمن کا ہے خونِ گرم دہقاں کا

خموشی میں نہاں خوں گشتہ لاکھوں آرزوئیں ہیں

چراغِ مردہ ہوں میں بے زباں گورِ غریباں کا

نظر میں ہے ہماری جادۂ راۂ فنا غالب

کہ یہ شیرازہ ہے عالم کے اجزاۓ پریشاں کا

In Jane Hirshfield's translation (The Enlightened Heart, Ed. Stephen Mitchell, Harper Perennial, 1989):

Let the ascetics sing of the garden of Paradise --

Who dwell in the true ecstasy can forget their vase-tamed bouquet.

In our hall of mirrors, the map of the one Face appears

As the sun's splendor would spangle a world made of dew.

Hidden in this image is also its end,

As peasants' lives harbor revolt and unthreshed corn sparks with fire.

Hidden in my silence are a thousand abandoned longings:

My words the darkened oil lamp on a stranger's unspeaking grave.

Ghalib, the road of change is before you always:

The only line stitching this world's scattered parts.

Tuesday, September 18, 2007

Political Liberalism

The United States government, independent of which party is in power, is more substantially based on the principles of political liberalism than governments of continental Europe, to say nothing of Iran or Cuba. Generally speaking, English-speaking countries like the USA, the UK, and Canada tend to have governments closer to ideal-typical political liberalism -- and therefore more freedom in civil society and less generous welfare states -- than others in the global North. Adherence to political liberalism in the USA is such that even many benefits and services that some Third-World governments that are more populist than socialist -- such as the Iranian government -- provide as citizens' entitlements are not provided by the government here. You have to shop for them on your own instead.

It's the same strong adherence to the principles of political liberalism that has created a polity in the USA that lets you freely establish businesses and voluntary associations (whether they are socially beneficial or detrimental) in the private sector, allows governments, corporations, medical professions, and so on to freely provide -- and more typically freely withhold -- an extremely wide range of goods and services, and also helps religious institutions, exempt from many laws and regulations, flourish in the USA.

In short, political liberalism tends to privatize, expanding the space for freedom (of the negative sort, freedom from government regulation, the only kind of freedom that Americans recognize as freedom) -- sexual and religious, as well as political and economic, freedoms -- in the private sector and contracting the scope of the public sector that provides citizens with goods and services as a matter of their rights. The American citizen has few social duties but also few social rights, the opposite of the Cuban or Iranian citizen who has many social duties but also many social rights. In the USA, the main obstacle to social rights is the strength of political liberalism that lets everyone in civil society -- individuals, corporations, religious institutions, and so on -- have a great deal of freedom of choice . . . if they can afford it.

It's the same strong adherence to the principles of political liberalism that has created a polity in the USA that lets you freely establish businesses and voluntary associations (whether they are socially beneficial or detrimental) in the private sector, allows governments, corporations, medical professions, and so on to freely provide -- and more typically freely withhold -- an extremely wide range of goods and services, and also helps religious institutions, exempt from many laws and regulations, flourish in the USA.

In short, political liberalism tends to privatize, expanding the space for freedom (of the negative sort, freedom from government regulation, the only kind of freedom that Americans recognize as freedom) -- sexual and religious, as well as political and economic, freedoms -- in the private sector and contracting the scope of the public sector that provides citizens with goods and services as a matter of their rights. The American citizen has few social duties but also few social rights, the opposite of the Cuban or Iranian citizen who has many social duties but also many social rights. In the USA, the main obstacle to social rights is the strength of political liberalism that lets everyone in civil society -- individuals, corporations, religious institutions, and so on -- have a great deal of freedom of choice . . . if they can afford it.

Ubi Lenin, Ibi Jerusalem

In the Presbyterian household of my partner's family (his father is a retired Presbyterian pastor), his marriage to an alien historical materialist who refuses to be fruitful and multiply caused no ideological ripple, but his youngest brother and his wife's exploration of Unitarian Universalism did. My father- and mother-in-law muttered, "But Unitarian Universalists have no creed." They, wise people, correctly understand that historical materialism is a creedal religion (albeit a creed increasingly more honored in the breach than the observance), thus more like their faith than Unitarian Universalism, New Age philosophy, or the ideology of those who say they have "no religious affiliation" and who do not have any other affiliation either.

Ubi Lenin, Ibi Jerusalem

Ubi Lenin, Ibi Jerusalem

Monday, September 17, 2007

Pleasure of Sex Education in Iran

In your sex education classes in schools in the USA, did you ever hear anything about techniques of pleasure, e.g., "men needed to be patient, because women need more time to become aroused"?

The secular liberal democratic government of the United States, which governs a rich industrial country in the global North, fails to provide such essential services as free contraceptives and scientific sex education, let alone a sex education that promotes sexual pleasure, which the Islamic Republic of Iran makes available.

Secular leftists tend to believe that secular liberal democracy is always better than religious government at least on the gender and sexuality front in all respects. But that is not true. It really depends on the content of each government's programs, not on whether the government is secular or religious.

The instructor held up an unfurled green condom as she lectured a dozen brides-to-be on details of family planning. But birth control was only one aspect of the class, provided by the government and mandatory for all couples before marriage. The other was about sex, and the message from the state was that women should enjoy themselves as much as men and that men needed to be patient, because women need more time to become aroused.

This is not the picture of Iran that filters out across the world, amid images of women draped in the forbidding black chador, or of clerics in turbans. But it is just as much a part of the complex social and political mix of Iranian society -- and of the state’s continuing struggle, now three decades old, to shape the identity of its people.

. . . Sex education here is not new, but the message has been updated recently to help young people enjoy each other and, the Islamic state hopes, strengthen their marriages in a time when everyday life in Iran is stressful enough. (Michael Slackman, "Molding the Ideal Islamic Citizen," New York Times, 9 September 2007)

ایران جالبترین کشور است!

The secular liberal democratic government of the United States, which governs a rich industrial country in the global North, fails to provide such essential services as free contraceptives and scientific sex education, let alone a sex education that promotes sexual pleasure, which the Islamic Republic of Iran makes available.

Secular leftists tend to believe that secular liberal democracy is always better than religious government at least on the gender and sexuality front in all respects. But that is not true. It really depends on the content of each government's programs, not on whether the government is secular or religious.

Ruthless Criticism of All That Exists

Marx wrote in a letter to Ruge (September 1843):

But are leftists really in favor of "ruthless criticism of all that exists," if the criticism in question gets extended to liberalism, which most leftists have adopted, often without realizing that they have done so, especially through their uncritical adoption of secularism? That remains to be seen.

Political liberalism protects capitalism through its public-private distinction. As Stanley Fish sums it up in his New York Times blog ("Liberalism and Secularism: One and the Same," 2 September 2007), liberalism is an ideology that

1 Mark Lilla calls the aforementioned public-private distinction the "Great Separation" in his essay titled "The Politics of God" (New York Times, 19 August 2007). Siva Vaidhyanathan says in his response to Lilla:

The internal difficulties seem to be almost greater than the external obstacles. For although no doubt exists on the question of "Whence," all the greater confusion prevails on the question of "Whither." Not only has a state of general anarchy set in among the reformers, but everyone will have to admit to himself that he has no exact idea what the future ought to be. On the other hand, it is precisely the advantage of the new trend that we do not dogmatically anticipate the world, but only want to find the new world through criticism of the old one. Hitherto philosophers have had the solution of all riddles lying in their writing-desks, and the stupid, exoteric world had only to open its mouth for the roast pigeons of absolute knowledge to fly into it. Now philosophy has become mundane, and the most striking proof of this is that philosophical consciousness itself has been drawn into the torment of the struggle, not only externally but also internally. But, if constructing the future and settling everything for all times are not our affair, it is all the more clear what we have to accomplish at present: I am referring to ruthless criticism of all that exists, ruthless both in the sense of not being afraid of the results it arrives at and in the sense of being just as little afraid of conflict with the powers that be.Today, a similar confusion prevails on the question of "Whither." If anything, in this post-socialist and post-social democratic age, when old modes of resistance have disappeared, we are even in greater need of "ruthless criticism of all that exists, ruthless both in the sense of not being afraid of the results it arrives at and in the sense of being just as little afraid of conflict with the powers that be" than men and women of Marx's times.

But are leftists really in favor of "ruthless criticism of all that exists," if the criticism in question gets extended to liberalism, which most leftists have adopted, often without realizing that they have done so, especially through their uncritical adoption of secularism? That remains to be seen.

Political liberalism protects capitalism through its public-private distinction. As Stanley Fish sums it up in his New York Times blog ("Liberalism and Secularism: One and the Same," 2 September 2007), liberalism is an ideology that

insists . . . on a form of government that is, in legal philosopher Ronald Dworkin's words, "independent of any particular conception of the good life." Individual citizens are free to have their own conception of what the good life is, but the state, liberal orthodoxy insists, should neither endorse nor condemn any one of them (unless of course its adherents would seek to impose their vision on others).Today, most leftists, even many Marxists, take it for granted that religion ought to stay in the place where liberalism has confined it. However, Marxism, to be true to its vocation, cannot abide by the "public-private distinction that liberalism depends on and enforces"1 for the benefit of capitalism. Nor can religion if it is to be a vehicle of resistance of masses rather than a means for their domestication. Nor can even a strong populism of the sort embodied in the Bolivarian process, which is the reason why liberals are increasingly alarmed by its direction. In short, by siding with liberals on where and how the distinction between public and private is to be drawn, leftists are unwittingly reinforcing the cage that imprisons not only religion but also their own ideology.

It follows then that the liberal state can not espouse a particular religion or require its citizens to profess it. Instead, the liberal state is committed to tolerating all religions while allying itself with none. Indeed, Starr declares, "the logic of liberalism" is "exemplified" by religious toleration. For if the idea is to facilitate the flourishing of many points of view while forestalling "internecine… conflicts" between them, religion, the most volatile and divisive of issues, must be removed from the give and take of political debate and confined to the private realm of the spirit, where it can be tolerated because it has been quarantined.

Thus the toleration of religion goes hand in hand with -- is the same thing as -- the diminishing of its role in the society. It is a quid pro quo. What the state gets by "excluding religion from any binding social consensus" (Starr) is a religion made safe for democracy. What religion gets is the state's protection. The result, Starr concludes approvingly, is "a political order that does not threaten to extinguish any of the various theological doctrines" it contains.