«L'unica soluzione -- conclude Henwood -- sarebbe per i democratici un grande piano di opere pubbliche, visto che le nostre infrastrutture -- ponti, strade, ferrovie, reti elettriche, aeroporti - stanno letteralmente andando in rovina. Questo piano consentirebbe aumento dell'occupazione, la ripresa economica e anche succosi profitti per il capitale. Ma nessun democratico si sogna di proporlo perché per finanziare queste opere pubbliche bisognerebbe reintrodurre una parziale progressività fiscale e questo, nei tempi che corrono, è una tabù, un'eresia che ti può mandare al rogo (politicamente parlando)».Moreover, a question may be asked: even if the Democrats were to propose "a grand plan of public works," would it be possible given the political economy of the United States?

"The only solution," concludes Henwood, "for the Democrats would be a grand plan of public works, inasmuch as our infrastructures -- bridges, roads, railroads, electrical grids, airports -- are literally falling apart. This plan would allow job growth, economic recovery, and also plenty of profits for capital. But no Democrat dreams of proposing it because, in order to finance these public works, it would have to introduce a little fiscal progressivity, and this, for the time being, is a taboo, a heresy that can condemn you to be burned at the stake (politically speaking)."

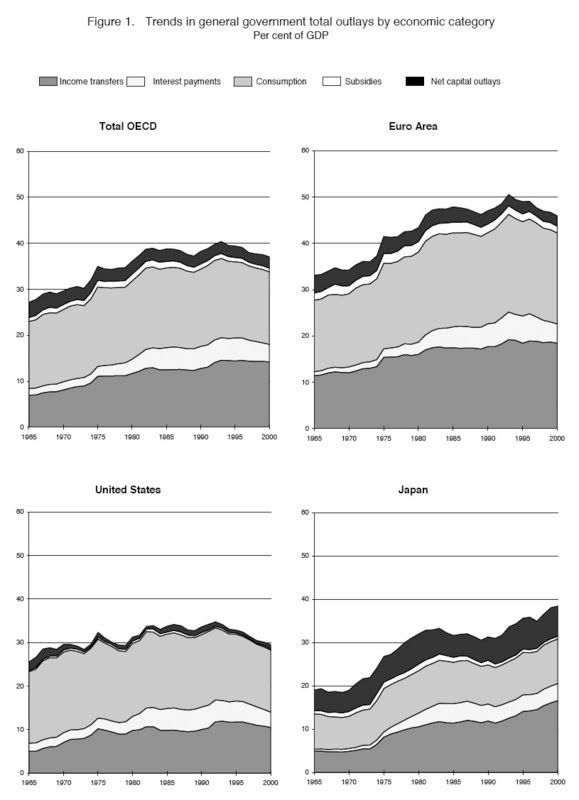

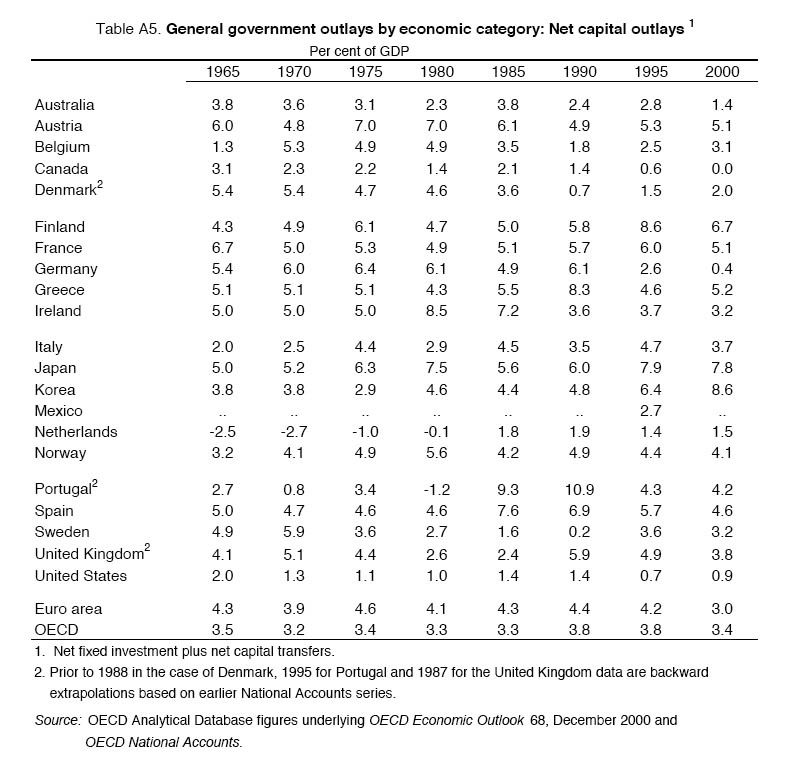

In Japan, the worst impacts of deflation during the 1990s were mitigated by public works as well as government loans to the private sector. The net capital outlay of the Japanese government in 1995 was 7.9 percent of GDP, more than double the OECD average (Paul Atkinson and Paul van den Noord, "Managing Public Expenditure: Some Emerging Policy Issues and a Framework for Analysis," Economics Department Working Papers No. 285, OECD, 8 February 2001).

SOURCE: Atkinson and Van den Noord, P. 6

SOURCE: Atkinson and Van den Noord, p. 49

More to the point, the Japanese government could take this option because it had at its disposal gigantic postal savings, whose size in 2006 was "roughly 65% of Japan's GDP" (Thomas F. Cargill and Hal S. Scott, "Postal Savings in Japan and Mortgage Markets in the U.S.," FRBSF Economic Letter, 3 March 2006).

Not so with the US government. The massive US current account deficit puts downward pressures on the dollar: "The United States borrows a whopping $2.5 billion daily from abroad to service its burgeoning debt," a result of "a manufacturing base that has declined 60 percent since World War II" (Hamid Varzi, "A Debt Culture Gone Awry," International Herald Tribune, 17 August 2007). At the same time, higher energy prices and rising inflation in China make for more inflationary pressures. Combined, they cannot but narrow the options of the US government in fiscal and monetary policies even as US economy, which has barely begun to experience the deflation of debt-financed asset bubbles, heads into recession.

In short, there is no organized sector of the US population capable of pushing and willing to push for a solution to the problem of US economy that would favor US workers; and, in any case, options available to US workers have already been narrowed considerably and will be narrowed further in the near future.

The US economy facing serious trouble does have a silver lining: for the first time since the end of World War 2, there is an objective potential to put an end to the dollar hegemony, the economic pillar of US imperialism. For everyone else besides hapless Americans, now may very well be a time between ashes and roses.

A time between ashes and roses is coming

When everything shall be extinguished

When everything shall begin.

-- Adonis, "An Introduction to

the History of the Petty Kings"

2 comments:

I thought the US government also had all that postal savings at its disposal. But I guess the firms investing for most Japanese bought REITs instead.

I think the best thing the Japanese government could do (isn't postal privatisation, though that is going ahead anyway) to re-flate the Japanese economy would be to raise interest rates. Most Japanese families are sitting on piles of savings that earn nothing. No wonder they don't feel like splurging on many things.

Unlike the big, post-big bang banks in Japan, the Japan Postal Savings BANK (post-privatisation) made a huge amount off bonds investing, little or no exposure to the sub-prime disease, unlike the banks. Bonds means corporate and government debt; I wonder if that means huge exposure to US government bonds.

See this Bloomberg report up at JT:

http://search.japantimes.co.jp/cgi-bin/nb20071227n1.html

hursday, Dec. 27, 2007

Japan Post Bank profit rises 20%

Bloomberg

Japan Post Bank Co. said Wednesday its first-half profit rose about 20 percent on increased returns from bond investments, including government debt.

Net income rose to ¥372.6 billion for the six months to Sept. 30, from ¥309.2 billion a year earlier, the Tokyo-based company said. Post Bank, independent since October when the postal system was privatized and split into three parts, has about ¥181 trillion in deposits, the most in the world.

Post Bank's earnings dwarf those of Japan's biggest publicly traded banking groups. Combined first-half profit at the six biggest, led by Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group Inc., fell by about half to ¥947.9 billion, partly because of losses on securities linked to subprime U.S. mortgages.

Mitsubishi UFJ said in November its net income dropped 50 percent to ¥256.7 billion in the first half. Profit slid 17 percent at Mizuho Financial Group Inc. as it posted a ¥70 billion subprime-related loss.

Post a Comment