The Iraq War -- especially fear of killing and dying in combat -- made all categories of youths less likely to join the military: fear of death and injury is "the top reason to avoid service for 26 percent of youth in 2004, almost double the 14 percent reported in 2000" (Philpott, March 6, 2005). Blacks' reasons for refusing to join the military, however, show a higher level of political consciousness than those of other groups: "Black youth were less supportive of U.S. troops' presence in Iraq, less likely to feel the war was justified, more disapproving of the Bush administration's handling of foreign affairs and more disapproving of its use of U.S. military forces than were whites or Hispanics," according to the Defense Department's Youth and Influencer Polls (qtd. in Philpott, March 6, 2005). Counter-recruitment activists should take note of the fact that parents -- particularly mothers -- are the most important influence, especially in Black communities: "A July 2004 study of parents' influence on young people of recruiting age found that black parents have more say in their child's career decisions than is the case with white parents. Also, black parents trust the military less and have more moral objections to military service" (Burns, March 8, 2005). It makes sense to emphasize community organizing more than campus organizing for the purpose of counter-recruitment.

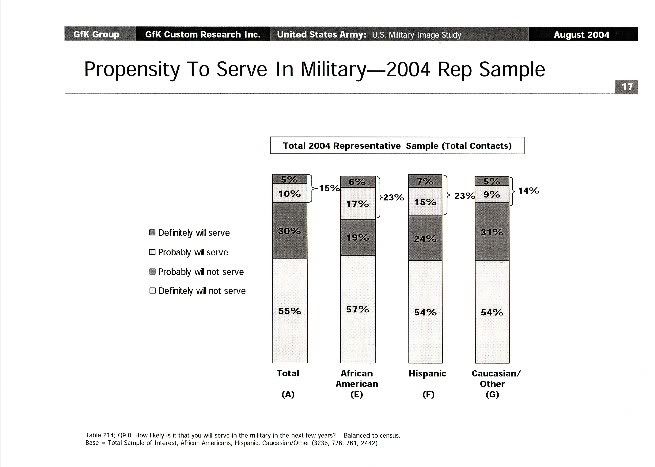

The "propensity to serve" is thankfully very low, according to the "U.S. Military Image Study" (August 4, 2004) prepared for the Army (which both Burns and Philpott cite in the aforementioned articles).

What makes a minority of young people still consider enlistment? The top reason is, not surprisingly, money for college: 42% mention "education," and 27% specifically say that "pay for education/$ for college" is the top-of-mind reason for joining the military ("U.S. Military Image Study," August 4, 2004). That means that the anti-war movement is inseparable from a movement for economic justice. Already, the equivalent of four-year scholarships at public universities for "7,499,971 students" (National Priorities Project, Cost of War, March 8, 2005) has been spent on the Iraq War! Activists have to struggle harder for more state subsidies to higher education and lower tuitions and fees, so that all who want to go to college can do so without risking their lives in Iraq or anywhere else.

Last not the least, the "U.S. Military Image Study" is worth reading in its entirety, as it presents many fascinating findings that have not been reported by the media. To take just one example, the study, in the inimitable language of marketing experts, offers an unintentionally funny recommendation to the Army in its conclusion: "For the Army to achieve its mission goals with Future Force Soldiers, it must overhaul its image as well as its product offering" . . . because, "[i]n today's reality, the risk/reward ratio is even more out of balance" than usual (emphasis added, August 4, 2004, p. 98).

2 comments:

"Your wrong" about the idea that the African-American is afraid of being killed, so that's why the enlistment rate for the Army is low. If you did a little more research you would find that the african-american are getting better educated, going to college and getting better paying jobs than before. Try and put that down and you will discover that the enlistment rate is down alittle because people choose to become more then jusst a soldier.

Neither the "U.S. Military Image Study" nor the newspaper articles cited above nor my essay you comment upon suggests that Blacks are more afraid of being killed and injured than other races. "[F]ear of death and injury" is shared by young people of all races. The reason why Black military enlistment declined more steeply than other races' is that Black youths, as well as their parents, are more politically conscious and critical of militarism and imperialism than those of other races. To repeat, "Black youth were less supportive of U.S. troops' presence in Iraq, less likely to feel the war was justified, more disapproving of the Bush administration's handling of foreign affairs and more disapproving of its use of U.S. military forces than were whites or Hispanics," according to the Defense Department's Youth and Influencer Polls (qtd. in Philpott, March 6, 2005).

The direction of the secular trend in literacy and education is clear: from fewer to more literate and educated individuals. See, for instance, the National Center for Education Statistics's "Literacy from 1870 to 1979: Illiteracy" (at http://nces.ed.gov/naal/historicaldata/illiteracy.asp). The biggest story of literacy and education from the late 19th to the late 20th century is a radical decline of Black illiteracy: from 79.9% in 1870 to 1.6% in 1979.

Since then, Americans of all races -- including Blacks, especially Black women -- have become even more educated, but better education has not translated into higher real wages (adjusted for inflation), as I explained in my essay "American Workers: Smarter but Poorer" (4 Mar. 2005, http://montages.blogspot.com/2005/03/american-workers-smarter-but-poorer.html).

In any event, the trend toward higher educational attainment did not suddenly accelerate in 2000, so it cannot account for a rapid decline in enlistment since then.

Post a Comment