Larry Elliott said earlier that "[t]hree things worked in Argentina's favour" in bargaining with creditors: "Firstly, [Nestor] Kirchner's hand was strengthened by the good performance of the economy. Secondly, the IMF was heavily exposed and knew that any deal was better than no deal. Finally, Wall Street had moved out of Argentina before the crisis, and it was the European banks which were left holding the baby. The US treasury was therefore under no real pressure to take a tough line with Argentina, and was apprehensive that Kirchner might forge a powerful populist front with president Lula of Brazil" (Larry Elliott, "Who Needs the Hand of God?" The Guardian 7 Mar. 2005). Judge Griesa's ruling in favor of Argentina, too, is probably due to the same three reasons that Elliott explains above.

Meanwhile, Brazil declared that it would "not renew a $41.75 billion loan accord with the International Monetary Fund when it expires this month, braving global financial markets on its own for the first time since 1998" (Andrew Hay, "Brazil to End IMF Support for First Time since '98," Reuters 28 Mar. 2005). More symbolic than anything else, since Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, assuming office in January 2003, "raised budget surplus goals above those stipulated by the IMF accord and renewed the deal for an extra 15 months in November 2003" (emphasis added, Hay, 28 Mar 2005) and, even without the IMF, "[t]he [Brazilian] government would maintain its current primary budget surplus target of 4.25 per cent of gross domestic product" and "continue to pursue the structural reform agenda it announced late last year," according to Finance Miniser Antonio Palocci (Raymond Colitt, "Brazil Ends $40bn IMF Loan Accord," Financial Times 29 Mar. 2005)? Nevertheless, the decision creates a political opening for the left, as the government can no longer say that the IMF made it do it when it confronts oppositions to its own neoliberal policy.

The rest of the world now has three precedents of defaults -- Russia, Brazil, and Argentina -- followed by economic recovery. According to Prensa Latina:

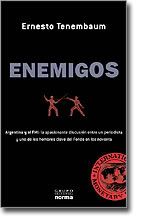

Mexico praised Brazil and Argentina for effectively negotiating their debt with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and drawing a line against abusive economic policies.With sovereignty -- i.e. national governments taking "social needs into their own hands" -- comes political responsibility. Enemigos (published in October 2004) -- Argentine journalist Ernesto Tenembaum's interview with former director of the IMF's Western Hemisphere Department Claudio Loser -- has been a bestseller in Argentina.

La Jornada daily said that despite differences both countries turned into a powerful weapon by pleading defaults of 28 and 3.1 billion US dollars respectively.

The daily claims they have set a key precedent for Latin America to successfully stay sovereign by taking their social needs into their own hands despite huge debts with the IMF. ("Brazil and Argentina Praised for IMF Dealings," 30 Mar. 2005)

In the next economic turmoil, whom will Argentines and Brazilians see as their primary enemy?

No comments:

Post a Comment