What's the implication of Tena's conviction for freedom of speech? Not much, according to Le Monde Informatique:

Néanmoins, le récent jugement du Tribunal Correctionnel de Paris ne porte pas sur le fond de l'affaire - un domaine sur lequel Tegam ne s'est pas encore aventuré - mais plutôt sur les méthodes employées par Guillaume Tena pour produire ses affirmations. Ainsi, le Tribunal condamne Guillermito pour avoir employé une copie pirate de Viguard. Du coup, le jugement ne semble pas remettre en cause le droit de critiquer, preuves à l'appui, les failles d'un produit. En revanche, il insiste bien sur le fait que ces preuves ne peuvent être obtenues illégalement. (E. C., "Guillaume Tena, condamné pour avoir utilisé frauduleusement Viguard," March 12, 2005)However, what is the definition of "a pirated copy" of software? As an article about the Guillermito affair at the K-OTik Security website explains, what Guillaume Tena did -- to disassemble and reverse-engineer software and publish exploits (codes that exploit security flaws of the software) to alert the public as well as the manufacturer of the software -- is "a common thing." TEGAM claimed that Tena's action was tantamount to counterfeit and piracy, and the French court apparently agreed with the company, but should the court have?

Nevertheless, the recent judgment of the Criminal Court of Paris does not go to the bottom of the affair -- a domain on which Tegam didn't venture yet -- but rather on the methods employed by Guillaume Tena to produce his assertions. Thus, the court convicts Guillermito of having employed a pirated copy of Viguard. So, the judgment does not appear to call the right to criticize the shortcomings of a product, with proofs to support the criticism, into question. On the other hand, it rightly insists on the fact that proofs cannot be obtained illegally. (E. C., "Guillaume Tena, Convicted of Fraudulent Use of Viguard," March 12, 2005)

L'affaire remonte à 2001, quand Guillaume Tena (connu sous le pseudonyme Guillermito) identifie puis publie dans des forums spécialisés, un certain nombre d'articles décrivant les faiblesses d'un logiciel antivirus français qui, selon son éditeur, est capable d'arrêter 100% des virus.Doesn't it look like another case of the rights of property owners run amok, defeating the rights of free speech and inquiry for the public good?

L'éditeur de l'antivirus en question n'a pas apprécié les critiques de ce chercheur et a donc déposé plainte contre X. Mis en examen pour "contrefaçon et recel de contrefaçon", Tena se voit reprocher, entre autres, la publication d'un Proof of Concept (Exploit) "reprenant et copiant une partie de la structure/code de l'antivirus" (désassemblage), violant ainsi l'article 335.2 du code de la propriété intellectuelle. L'expert informatique désigné par le juge d'instruction a donc conclu que "le délit de contrefaçon par reproduction de logiciel était caractérisé dans la mesure où les modifications sur l'antivirus n'étaient pas effectuées par un simple utilisateur à des fins de compatibilité pour une utilisation personnelle, mais étaient réalisées par un internaute qui les communique à des tiers".

Or, la publication d'exploits ou de Proof of Concept est chose courante dans le monde de la sécurité, puisqu'ils permettent de confirmer l'existence d'un bug ou d'une faille de sécurité, et d'évaluer les risques réels qu'encourent les internautes utilisant un produit vulnérable. L'expert à précisé toutefois que "Guillaume Tena disposait de compétences indiscutables en matière virale et anti-virale, et avait dénoncé avec pertinence les failles de cet antivirus".

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Une éventuelle condamnation de Guillermito pourrait tuer la recherche et la divulgation des failles de sécurité en France, une recherche déjà "bridée" par l'article 46 de la Loi pour la confiance dans l'économie numérique (Loi n° 2004-575 du 21 Juin 2004- JO n° 143 du 22 Juin 2004).

La révélation d'une faille de sécurité nécessiterait alors, non seulement un "motif légitime", mais aussi l'accord préalable de l'éditeur ou du constructeur, une situation inimaginable et inacceptable dans tout autre domaine de recherche scientifique [imaginez le scandale si une société pharmaceutique portait plainte contre un chercheur biologiste ayant révélé, par exemple, qu'un médicament commercialisé n'était pas aussi efficace que ce que prétendait le laboratoire produisant ce médicament].

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Update :

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

En créant un précédent judiciaire, cette condamnation pourrait, à l'avenir, s'avérer dangereuse pour l'ensemble des chercheurs et des professionnels de la sécurité informatique, car la publication d'une vulnérabilité ou d'un Proof of Concept à partir de recherches effectuées par reverse engineering ou par désassemblage est désormais ILLEGALE.

L'étude ou l'analyse des vulnérabilités présentes au sein d'un logiciel non Open-Source est, à partir d'aujourd'hui, interdite en France... (La Rédaction/K-OTik Security, "Affaire Guillermito -- Le full-disclosure français jugé en 2005," August 31, 2004 - March 8, 2005)

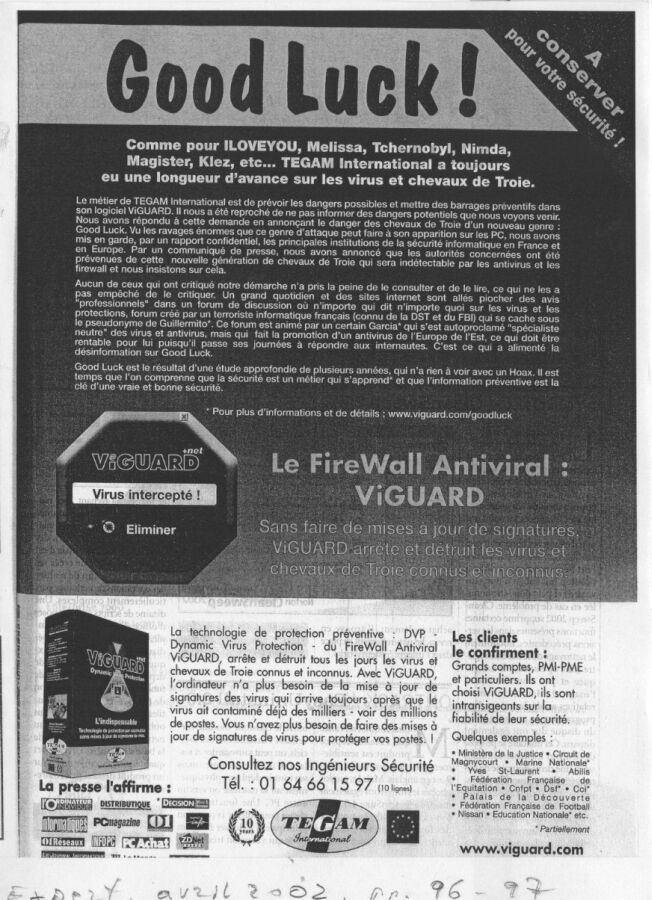

The affair goes back to 2001, when Guillaume Tena (known by his pseudonym Guillermito) identified and published, in specialized forums, a certain number of articles describing the weaknesses of a French anti-virus program which, according to its publisher, is capable of stopping all viruses.

The publisher of the anti-virus software in question did not appreciate the researcher's criticisms and thus lodged a complaint against X. Indicted for "counterfeit and concealment of counterfeit," Tena is blamed for, among others, the publication of a Proof of Concept (Exploit) "seizing and copying a part of the structure/code of the anti-virus program" (disassembly), thus violating article 335.2 of the code of intellectual property. The information technology expert appointed by the examining judge then concluded that "the offence of counterfeit by reproduction of software was clear-cut insofar as the modifications on the anti-virus program were not carried out by a simple user for compatibility for personal use, but were carried out by an Internet expert who communicates them to third parties".

But, the publication of exploits or Proof of Concept codes is a common thing in the world of computer security, since they make it possible to confirm the existence of a bug or a security flaw and to evaluate the real risks which the Net surfers using a vulnerable product incur. The expert, nevertheless, clarified that "Guillaume Tena had indisputable competencies in viral and anti-viral matters and blew the whistle on the weaknesses of this anti-virus program."

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

A possible conviction of Guillermito could kill the research and disclosure of security weaknesses in France, research already "restrained" by article 46 of the law for confidence in the digital economy (Law n° 2004-575 of June 21 2004 - OJ n° 143 of June 22, 2004).

The revelation of a security flaw would then require not only a "legitimates reason" but also prior agreement of the publisher or manufacturer, an unimaginable and unacceptable situation in any other field of scientific research (imagine the scandal if a pharmaceutical company lodged a complaint against a biologist for having revealed, for example, that a marketed drug was not as effective as the laboratory producing it claimed).

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Update:

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

By creating a legal precedent, this judgment could, in the future, prove to be dangerous for all computer security researchers and professionals, because the publication of a vulnerability or Proof of Concept based on research by reverse engineering or disassembly is ILLEGAL from now on.

The study or analysis of vulnerabilities present within non-open-source software is, beginning today, prohibited in France. . . (La Rédaction/K-OTik Security, "Guillermito Affair -- French Full-Disclosure Judged in 2005," August 31, 2004 - March 8, 2005)

Note, also, that, according to Tena, TEGAM accused him "publically six or seven times at the beginning of 2002 to be a 'terrorist wanted by the DST (French secret service) and the FBI', and a 'computer pirate'" (emphasis added, "Indicted," March 5, 2004):

That's a typical tactic of corporations attempting to silence their critics, employed beyond the battleground of copyright disputes. Corporations even specifically hire "public relations agencies and research companies" to troll the Net looking for their critics and study how to respond to them:

Now some public relations agencies and research companies are studying determined detractors, dividing them into different groups defined by motivation, monitoring their complaints and trying to help corporate clients decide how to react.Paul Rand, managing director of one such public relations firm Ketchum Midwest, calls the most determined and persistent critics "reputation terrorists" (Ives, December 28, 2004). For obvious reasons, many companies would be tempted to label critics "reputation terrorists" and dismiss or attack them as such, however legitimate their criticisms may be, if the criticisms gain wide publicity, threatening to diminish the companies' profits.

BuzzMetrics, a New York-based specialist in word-of-mouth marketing, has developed proprietary software to scoop up information on trendsetters and potential influencers as they travel the Internet, posting messages on bulletin board sites, updating personal Web pages and sharing information through e-mail mailing lists.

"For brand managers, the big challenge is to predict trouble on the horizon," said Jonathan Carson, head of BuzzMetrics. "When they see a detractor they have to figure out whether it's a single disgruntled customer or an actual smoldering crisis that could explode."

BuzzMetrics would not identify by name the 20 or so marketers it says have used, or are now using, its crisis management or prevention services, but Carson said the clients included several pharmaceutical companies. BuzzMetrics also looked into the threat posed to a French conglomerate when some supporters of the Iraq invasion were circulating a boycott list. (Nat Ives, "Firms Grow Wary of Foes on Web ," New York Times/International Herald Tribune, December 28, 2004)

Corporations' copyright and reputation vs. people's right to free speech and inquiry -- the Guillermito affair dramatizes a new type of class struggle increasingly common under late capitalism.

No comments:

Post a Comment