Friday, August 29, 2008

Russia, China, and Empire

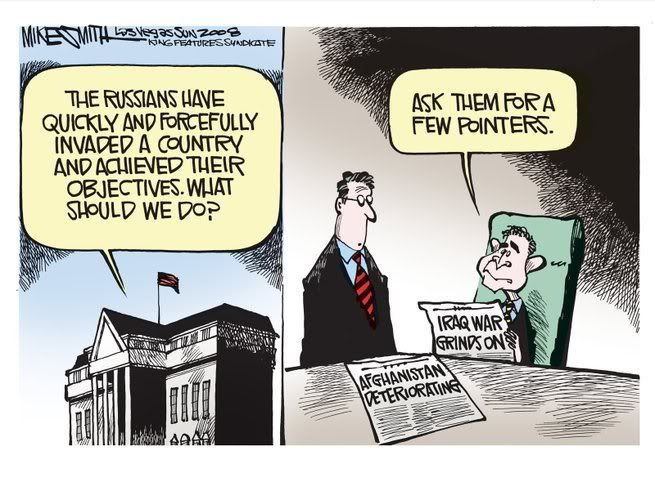

If Washington is smart, it will try to peel China away from Russia, dropping Tibet and Xinjiang in particular and human rights in general. Then again, though, if Washington were really smart, if wouldn't have invaded Iraq and Afghanistan and tried to work against both Iran and Russia at the same time. Meanwhile, the Chinese are dropping the US agency debt.

Thursday, August 28, 2008

The Return of Russia

The Return of Russia

by Serge Halimi

The question of responsibility for the conflict in the Caucasus didn't trouble us for long. Less than a week after the Georgian attack, two French commentators, experts on all things, pronounced it "obsolete." An influential American neo-conservative had set the tone for them. Knowing who started the conflict is "not very important," Robert Kagan opined, because, "[i]f Saakashvili had not fallen into Putin's trap this time, something else would have eventually sparked the conflict."1 One hypothesis calls for another: if it had not been the young polyglot Saakashvili, a graduate of Columbia Law School in New York, who initiated a military operation, on the day of the opening ceremony of the Olympics no less, would Western governments and their media have held back their outrage against such a heavily symbolic act?

But when you know good and bad characters in advance, it is easier to follow the story. The good, like Georgia, have a duty to protect their territorial integrity from separatist schemes hatched by their neighbors; the bad, like Serbia, would have to agree to the self-determination of their Albanian minority (Kosovo) . . . or else be subjected to the bombing by the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). The moral of the story gets even more edifying when, to defend his territory, the good pro-American president brings home a division of soldiers whom he sent . . . to invade Iraq.

On the 16th of August, President George W. Bush correctly invoked, with all seriousness, the "resolutions" of the "United Nations Security Council" and the "sovereignty and independence and territorial integrity" of Georgia whose "borders should command the same respect as every other nation's." It follows that only the United States must have the right to act unilaterally when it perceives (or pretends) that its security is at stake. In reality, this series of events follows a simpler logic: Washington uses Georgia (and vice versa) to work against Russia; Moscow uses not only South Ossetia but also Abkhazia to "punish" Georgia.

Since 1992, two reports of the Pentagon have explored the question of how to prevent a possible resurgence of the then crumbling Russian power. These reports indicated that, to perpetuate the American hegemony born of the victory of the United States in the Gulf War and the breakup of the Soviet bloc, it was important to "[convince] potential competitors that they need not aspire to a greater role." And, failing to convince them, Washington must "discourage" them. The main target of these considerations? Russia, "the only power in the world with the capability of destroying the United States."2

Can we then blame the Russian leadership for having experienced Western assistance to the "color revolutions" in Ukraine and Georgia, former Warsaw Pact allies' membership in the NATO, and the installation of American missiles on Polish soil as elements of the old strategy aimed to weaken their country, whatever its regime? Besides, Mr. Bernard Kouchner, French Foreign Minister, admitted as much: "Russia has become a great power, which is worrisome."3

The architect in 1980 of the very dangerous Afghan strategy of Washington (giving military support to Islamists to defeat communists. . .), Mr. Zbigniew Brzezinski has spelled out another aspect of the American design: "Georgia is of strategic importance because we have access through Georgia, through a pipeline that runs from Baku, the capital of Azerbaijan, through Tbilisi, the capital of Georgia, down to Turkey, and to the Mediterranean Ocean, a pipeline which gives us access to the oil, and soon also the gas, that lies not only in Azerbaijan, but beyond it in the Caspian Sea, and beyond it in Central Asia. So, in that sense, it's a major and very important strategic asset to us."4 Mr. Brzezinski cannot be accused of inconstancy: even when Russia was at its nadir in the era of Boris Yeltsin, he was trying to chase it out of the Caucasus and Central Asia to secure energy supply for the West.5 Since then, Russia has fared better, the United States worse, and oil is now more expensive. A victim of its own president's provocations, Georgia is being buffeted by the clash of these three dynamics.

1 Respectively, Bernard-Henri Lévy and André Glucksmann in the 14 August 2008 issue of Libération and Robert Kagan in the 11 August 2008 issue of the Washington Post.

2 Cf. Paul-Marie de La Gorce, "Washington et la maîtrise du monde," Le Monde diplomatique, April 1992.

3 Interview, Journal du dimanche, Paris, 17 August 2008.

4 Bloomberg Television, 12 August 2008.

5 Zbigniew Brzezinski, Le Grand Echiquier, Paris: Bayard, 1997.

Serge Halimi is a French journalist of Tunisian origin. He has written for Le Monde diplomatique since 1992 and served as the magazine's editorial director since March 2008. The original article "Retour russe" appears in the September 2008 issue of Le Monde diplomatique. English translation by Yoshie Furuhashi.

by Serge Halimi

The question of responsibility for the conflict in the Caucasus didn't trouble us for long. Less than a week after the Georgian attack, two French commentators, experts on all things, pronounced it "obsolete." An influential American neo-conservative had set the tone for them. Knowing who started the conflict is "not very important," Robert Kagan opined, because, "[i]f Saakashvili had not fallen into Putin's trap this time, something else would have eventually sparked the conflict."1 One hypothesis calls for another: if it had not been the young polyglot Saakashvili, a graduate of Columbia Law School in New York, who initiated a military operation, on the day of the opening ceremony of the Olympics no less, would Western governments and their media have held back their outrage against such a heavily symbolic act?

But when you know good and bad characters in advance, it is easier to follow the story. The good, like Georgia, have a duty to protect their territorial integrity from separatist schemes hatched by their neighbors; the bad, like Serbia, would have to agree to the self-determination of their Albanian minority (Kosovo) . . . or else be subjected to the bombing by the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). The moral of the story gets even more edifying when, to defend his territory, the good pro-American president brings home a division of soldiers whom he sent . . . to invade Iraq.

On the 16th of August, President George W. Bush correctly invoked, with all seriousness, the "resolutions" of the "United Nations Security Council" and the "sovereignty and independence and territorial integrity" of Georgia whose "borders should command the same respect as every other nation's." It follows that only the United States must have the right to act unilaterally when it perceives (or pretends) that its security is at stake. In reality, this series of events follows a simpler logic: Washington uses Georgia (and vice versa) to work against Russia; Moscow uses not only South Ossetia but also Abkhazia to "punish" Georgia.

Since 1992, two reports of the Pentagon have explored the question of how to prevent a possible resurgence of the then crumbling Russian power. These reports indicated that, to perpetuate the American hegemony born of the victory of the United States in the Gulf War and the breakup of the Soviet bloc, it was important to "[convince] potential competitors that they need not aspire to a greater role." And, failing to convince them, Washington must "discourage" them. The main target of these considerations? Russia, "the only power in the world with the capability of destroying the United States."2

Can we then blame the Russian leadership for having experienced Western assistance to the "color revolutions" in Ukraine and Georgia, former Warsaw Pact allies' membership in the NATO, and the installation of American missiles on Polish soil as elements of the old strategy aimed to weaken their country, whatever its regime? Besides, Mr. Bernard Kouchner, French Foreign Minister, admitted as much: "Russia has become a great power, which is worrisome."3

The architect in 1980 of the very dangerous Afghan strategy of Washington (giving military support to Islamists to defeat communists. . .), Mr. Zbigniew Brzezinski has spelled out another aspect of the American design: "Georgia is of strategic importance because we have access through Georgia, through a pipeline that runs from Baku, the capital of Azerbaijan, through Tbilisi, the capital of Georgia, down to Turkey, and to the Mediterranean Ocean, a pipeline which gives us access to the oil, and soon also the gas, that lies not only in Azerbaijan, but beyond it in the Caspian Sea, and beyond it in Central Asia. So, in that sense, it's a major and very important strategic asset to us."4 Mr. Brzezinski cannot be accused of inconstancy: even when Russia was at its nadir in the era of Boris Yeltsin, he was trying to chase it out of the Caucasus and Central Asia to secure energy supply for the West.5 Since then, Russia has fared better, the United States worse, and oil is now more expensive. A victim of its own president's provocations, Georgia is being buffeted by the clash of these three dynamics.

1 Respectively, Bernard-Henri Lévy and André Glucksmann in the 14 August 2008 issue of Libération and Robert Kagan in the 11 August 2008 issue of the Washington Post.

2 Cf. Paul-Marie de La Gorce, "Washington et la maîtrise du monde," Le Monde diplomatique, April 1992.

3 Interview, Journal du dimanche, Paris, 17 August 2008.

4 Bloomberg Television, 12 August 2008.

5 Zbigniew Brzezinski, Le Grand Echiquier, Paris: Bayard, 1997.

Serge Halimi is a French journalist of Tunisian origin. He has written for Le Monde diplomatique since 1992 and served as the magazine's editorial director since March 2008. The original article "Retour russe" appears in the September 2008 issue of Le Monde diplomatique. English translation by Yoshie Furuhashi.

Sunday, August 24, 2008

Getúlio Vargas

24 August 1954

Río de Janeiro

Getúlio

He puts himself on the side of wages, not profits. At once, businessmen declare war.

So that Brazil shall cease to be a sieve, he stops the hemorrhage of wealth. At once, foreign capital begins sabotage.

He regains control of oil and energy, which are national sovereignty as much as or more than the flag and the anthem. At once, monopolies, offended, retaliate with a ferocious offensive.

He defends the price of coffee without, as was the custom, burning half the harvest at the stake. At once, the United States cuts its purchases by half.

In Brazil, journalists and politicians of all regions and persuasions add their voices to the chorus of outrage.

Getúlio Vargas has governed on his feet. Forced to go down on his knees, he chooses the dignity of death. He picks up his revolver, aims it at his own heart, and fires.

The text above is a translation of an excerpt from Eduardo Galeano, El siglo del viento (Siglo XXI, 2000), pp. 188-189. Translation by Yoshie Furuhashi.

Monday, August 18, 2008

How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Climate Change

"Mr. President, we must not allow an icebreaker gap!"

A growing array of military leaders, Arctic experts and lawmakers say the United States is losing its ability to patrol and safeguard Arctic waters even as climate change and high energy prices have triggered a burst of shipping and oil and gas exploration in the thawing region.

The National Academy of Sciences, the Coast Guard and others have warned over the past several years that the United States’ two 30-year-old heavy icebreakers, the Polar Sea and Polar Star, and one smaller ice-breaking ship devoted mainly to science, the Healy, are grossly inadequate. Also, the Polar Star is out of service.

And this spring, the leaders of the Pentagon’s Pacific Command, Northern Command and Transportation Command strongly recommended in a letter that the Joint Chiefs of Staff endorse a push by the Coast Guard to increase the country’s ability to gain access to and control its Arctic waters.

In the meantime, a resurgent Russia has been busy expanding its fleet of large oceangoing icebreakers to around 14, launching a large conventional icebreaker in May and, last year, the world’s largest icebreaker, named 50 Years of Victory, the newest of its seven nuclear-powered, pole-hardy ships. (Andrew C. Revkin, "A Push to Increase Icebreakers in the Arctic," New York Times, 17 August 2008)

Sunday, August 17, 2008

Saturday, August 16, 2008

Uruguayan Writer Eduardo Galeano Apologizes for the War That Devastated Paraguay

Uruguayan Writer Eduardo Galeano Apologizes for the War That Devastated Paraguay

Asunción, 15 August (EFE) -- Uruguayan writer Eduardo Galeano today publicly apologized to Paraguayans for the war that his country, allied with Argentina and Brazil, fought against Paraguay between 1865 and 1870.

"Let me take this opportunity to apologize as an Uruguayan, because that [imperialist] punishment [for the crime of protecting the workers and products of the nation] was inflicted through three neighboring countries of Paraguay," Galeano said at a press conference in which Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez, Ecuadorian President Rafael Correa, and Paraguayan President Fernando Lugo participated.

The author of Open Veins of Latin America regretted his country's participation in a war "that was said to last three months" but lasted five years "and exterminated the entire adult male population of this country."

"That model was misnamed 'free trade,' which, as we know well, is a freedom that imprisons people, a big lie, because that's the name that the global North gives to everything that it preaches but doesn't practice," said the Uruguayan.

For his part, Boff expressed how pleased he was to have taken part in the civic festival in Paraguay today on the occasion of the inauguration of Lugo and said: "I think all who are at this table are for liberation, and for me, who comes from that theology, this is an extremely happy moment."

He reminded all that the purpose of this religious current "is to practice not so much theology as liberation, because what matters to God is not theology, it is the concrete liberation of individuals" and stressed that "the pressure of the poor has given a very powerful force to a government that realizes the dreams denied for so many generations."

Cardenal spoke in the same vein, describing Lugo as "true bishop of liberation."

Moreover, he said: "We are celebrating the rise to power of one more liberator of Latin America."

"A few days ago I was in Bolivia, and there I saw a miracle: an Indian president of Bolivia. Now I have seen another miracle here, too: a bishop president," said Cardenal.

In the end, Lugo said he was honored to have shared "a feast" with Galeano, Cardenal, and Boff and reaffirmed that he doesn't feel any fear about his friendly relation with the politics of Chávez, Morales, and Correa.

"People say: Don't be close to Chávez or Evo. I'm not afraid of Chávez, I'm not afraid of Evo, I'm not afraid of anyone. Latin America is living a different moment," said Lugo, who put an end to 61 years of the conservative Colorado Party hegemony in government.

The original EFE dispatch in Spanish was published in Yahoo! Noticias on 16 August 2008. Translation by Yoshie Furuhashi.

Asunción, 15 August (EFE) -- Uruguayan writer Eduardo Galeano today publicly apologized to Paraguayans for the war that his country, allied with Argentina and Brazil, fought against Paraguay between 1865 and 1870.

"Let me take this opportunity to apologize as an Uruguayan, because that [imperialist] punishment [for the crime of protecting the workers and products of the nation] was inflicted through three neighboring countries of Paraguay," Galeano said at a press conference in which Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez, Ecuadorian President Rafael Correa, and Paraguayan President Fernando Lugo participated.

Fernando Lugo, Presidente de Paraguay

con Leonardo Boff, Eduardo Galeano, y Ernesto Cardenal

The author of Open Veins of Latin America regretted his country's participation in a war "that was said to last three months" but lasted five years "and exterminated the entire adult male population of this country."

Guerra do Paraguai / Guerra del Paraguay

"That model was misnamed 'free trade,' which, as we know well, is a freedom that imprisons people, a big lie, because that's the name that the global North gives to everything that it preaches but doesn't practice," said the Uruguayan.

For his part, Boff expressed how pleased he was to have taken part in the civic festival in Paraguay today on the occasion of the inauguration of Lugo and said: "I think all who are at this table are for liberation, and for me, who comes from that theology, this is an extremely happy moment."

He reminded all that the purpose of this religious current "is to practice not so much theology as liberation, because what matters to God is not theology, it is the concrete liberation of individuals" and stressed that "the pressure of the poor has given a very powerful force to a government that realizes the dreams denied for so many generations."

Cardenal spoke in the same vein, describing Lugo as "true bishop of liberation."

Moreover, he said: "We are celebrating the rise to power of one more liberator of Latin America."

"A few days ago I was in Bolivia, and there I saw a miracle: an Indian president of Bolivia. Now I have seen another miracle here, too: a bishop president," said Cardenal.

In the end, Lugo said he was honored to have shared "a feast" with Galeano, Cardenal, and Boff and reaffirmed that he doesn't feel any fear about his friendly relation with the politics of Chávez, Morales, and Correa.

"People say: Don't be close to Chávez or Evo. I'm not afraid of Chávez, I'm not afraid of Evo, I'm not afraid of anyone. Latin America is living a different moment," said Lugo, who put an end to 61 years of the conservative Colorado Party hegemony in government.

The original EFE dispatch in Spanish was published in Yahoo! Noticias on 16 August 2008. Translation by Yoshie Furuhashi.

Friday, August 15, 2008

Mass Expulsion in Pakistan: In the Shadow of the Caucasus Crisis

Mass Expulsion in Pakistan:

In the Shadow of the Caucasus Crisis

by Knut Mellenthin

Russia's response to the Georgian aggression against South Ossetia has been the central theme of the media for a week, and it's scarcely noticed that the human tragedy in northwest Pakistan will probably be of no less great political significance. On Friday, the ninth day of a punitive military expedition against Bajaur Agency in the so-called tribal areas, over 100,000 people were seeking refuge. No one knows the exact number, which reflects the fact that there is no organized aid for refugees. An English-language Pakistani newspaper, The News, said on Friday that "several hundred thousands" were fleeing. News agencies reported that, according to the Governor of the North-West Frontier Province, into whose capital Peshawar tens of thousands fled, the number is about 219,000.

Many had to leave all their possessions behind, because the "security forces," in their campaign against suspected insurgents, repeatedly used heavy artillery, helicopters, and fighter planes against villages. In addition, there are systematic expulsions. Leaflets are dropped from helicopters, calling on people to immediately vacate certain areas. The leaflets contain detailed instructions about how to behave, any failure to comply with which carries the risk of lethal attacks by the "security forces": No vehicle movements after sunset. Cars may not be parked under trees, or in the shade. Upon seeing a helicopter, all refugees must come out of their vehicles with their hands up. Those who don't receive leaflets or cannot read -- a majority of the population in the area -- are in mortal danger. Air raids on refugee convoys are not uncommon. Many families are fleeing on foot. Those who were expelled or have simply fled are not supplied with food and medical care. Tens of thousands have to sleep outdoors.

Bajaur is one of many districts in which such punitive expeditions have taken place in recent months. The "security forces" had already similarly wreaked havoc in Swat and Hang before, outside the Federally Administered Tribal Areas, in the North-West Frontier Province. As the Pakistani media reported on Friday, now thousands are fleeing from Mohmand Agency, on the southern border of Bajaur. which it is suspected the "security forces" will strike next.

These military actions cannot be called appropriate or effective even for the purpose of the US/NATO counter-insurgency campaign. Their function is essentially to demonstrate to Washington, which is more and more aggressively putting pressure on Islamabad, that things are under control and there is no reason for a US intervention in Pakistan.

The original article in German appears in junge Welt on 16 August 2008. Translation by Yoshie Furuhashi.

In the Shadow of the Caucasus Crisis

by Knut Mellenthin

Russia's response to the Georgian aggression against South Ossetia has been the central theme of the media for a week, and it's scarcely noticed that the human tragedy in northwest Pakistan will probably be of no less great political significance. On Friday, the ninth day of a punitive military expedition against Bajaur Agency in the so-called tribal areas, over 100,000 people were seeking refuge. No one knows the exact number, which reflects the fact that there is no organized aid for refugees. An English-language Pakistani newspaper, The News, said on Friday that "several hundred thousands" were fleeing. News agencies reported that, according to the Governor of the North-West Frontier Province, into whose capital Peshawar tens of thousands fled, the number is about 219,000.

Many had to leave all their possessions behind, because the "security forces," in their campaign against suspected insurgents, repeatedly used heavy artillery, helicopters, and fighter planes against villages. In addition, there are systematic expulsions. Leaflets are dropped from helicopters, calling on people to immediately vacate certain areas. The leaflets contain detailed instructions about how to behave, any failure to comply with which carries the risk of lethal attacks by the "security forces": No vehicle movements after sunset. Cars may not be parked under trees, or in the shade. Upon seeing a helicopter, all refugees must come out of their vehicles with their hands up. Those who don't receive leaflets or cannot read -- a majority of the population in the area -- are in mortal danger. Air raids on refugee convoys are not uncommon. Many families are fleeing on foot. Those who were expelled or have simply fled are not supplied with food and medical care. Tens of thousands have to sleep outdoors.

Bajaur is one of many districts in which such punitive expeditions have taken place in recent months. The "security forces" had already similarly wreaked havoc in Swat and Hang before, outside the Federally Administered Tribal Areas, in the North-West Frontier Province. As the Pakistani media reported on Friday, now thousands are fleeing from Mohmand Agency, on the southern border of Bajaur. which it is suspected the "security forces" will strike next.

These military actions cannot be called appropriate or effective even for the purpose of the US/NATO counter-insurgency campaign. Their function is essentially to demonstrate to Washington, which is more and more aggressively putting pressure on Islamabad, that things are under control and there is no reason for a US intervention in Pakistan.

The original article in German appears in junge Welt on 16 August 2008. Translation by Yoshie Furuhashi.

Tuesday, August 12, 2008

International Capital Dominates Brazilian Agriculture

International Capital Dominates Brazilian Agriculture

by João Pedro Stedile

The Movement of Financial Capital

In recent years, there has been an intensive, continuous process of concentration and centralization of corporations operating and controlling the entire production process of global agriculture.

Concentration is the concept used in political economy to explain the movement of large corporations to combine, accumulate, and become large groups. Thus, in every sector of production, a situation of oligopoly is being created, with a few corporations controlling the sector. The second movement of capital is centralization, in which a single corporation comes to control several sectors of production, sometimes even the sectors unrelated to one another. These two logical movements of capital have been accompanied in the agricultural sector with a process of internationalization of control of the market and trade at the global level. In other words, some corporations have come to operate in every country and control the global market.

This dual movement of capital -- which was very much noticeable, from as far back as the theory of imperialism, in large industrial enterprises -- also came to dominate the agricultural sector in the last ten years. And what is most dangerous, now under the hegemony of financial capital, the velocity and volume of capital invested in agriculture were much faster and greater than had been the case in other productive sectors through the course of the twentieth century. That is because much capital in the form of money, i.e. financial capital, accumulated in rich countries in recent years. This capital was shifting to the purchase of shares in the most profitable corporations of the primary sector as well. Thus, in just a few years, as an effect of the investment of this financial capital in stock purchases, concentration and centralization became extraordinary.

Result

Today, almost all branches of agricultural production are controlled by groups of oligopolistic corporations, which coordinate among themselves. Thus, Cargill, Monsanto, ADM, Dreyfus, and Bunge alone are responsible for 80% of the total world production of and trade in grains such as soybeans, corn, wheat, rice, and sunflowers. Monsanto, Novartis, Bayer, and Syngenta control the entire production of transgenic seeds. In the dairy products and derivatives sector we come up against Nestlé, Dannon, and Parmalat. Here in Brazil, the entire production of raw materials for fertilizers is controlled by just three transnational corporations: Bunge, Mosaic, and Yara. Only two corporations, Monsanto and Nortox, produce glyphosate, a raw material for agricultural pesticides. AGCO, Fiat, New Holland, etc. oligopolize the agricultural machinery sector.

This movement, which had begun to develop in the 1990s, accelerated in the past two years with the crisis of capitalism in the United States. Interest rates in the core countries fell to an annual rate of 2% and, given the inflation rate, reached the point where banks would lose money. Then, financial capital shifted to the periphery of the system to protect itself from the crisis and maintain its profit rates. Over the past two years, nearly 330 billion dollars of money poured into Brazil. A part of that capital was invested through local banks, to encourage the buying of real estate, household appliances, and cars on credit, at the average annual rates of 47%. Sheer madness, compared with the rates in developed countries.

Another part of capital was destined to the purchase of lands. One report in the Folha de São Paulo newspaper estimated that foreign capital bought more than 20 million hectares in recent years, especially in the midwest regions and the new agricultural frontier of the so-called Ma-pi-to (Maranhão, Piauí, and Tocantis), where land prices were much lower. Yet another part headed to the Amazon in search of mining areas, hydroelectric projects, and possession of huge areas of biodiversity which later will bear fruit if they are exploited by their laboratories.

In the cellulose sector, three large groups -- Aracruz (Norway), Stora Enzo (Sweden-Finland), and International Paper (US) -- moved their entire production to the rich soil and climatic conditions found in Brazil. So, the expansion of eucalyptus monoculture throughout the region stretching from Bahía in the south to the Uruguay border and six new factories are being planned. Thousands of hectares of industrial eucalyptus plantations will destroy everything, creating a veritable green desert.

Likewise, there was a major investment of foreign capital in the expansion of sugarcane monoculture for ethanol production and export. The sugarcane area increased from 4 to 6 million hectares. There are 77 projects for new ethanol plants, which will be built along four major alcohol pipelines projected to transport alcohol from the midwest to the ports of Santos and Paranaguá and from the Palmas region (Tocantins State) to the port of São Luis (in Maranhão State). Two of these alcohol pipelines are owned by Petrobras and the other two will be owned by foreign investors.

Foreign capital also speeded up its investment in the production and multiplication of transgenic seeds, especially maize. Hence Syngenta, Monsanto, and Bayer are lobbying and pressuring the government to allow their varieties of GM corn. Some of these varieties are banned in Europe, but here . . . anything goes!

Agribusiness

This avalanche of foreign capital to control our agricultural production and inputs and to expand production for export was made possible only by the alliance of the aforementioned corporations and the big landowners. The landowners with large tracts of land are getting in on the action as subordinate associates of big corporations, plundering the environment, overexploiting agricultural labor, and sometimes even using slave labor.

This agricultural model, which is called agribusiness, is the marriage of transnationals and big landowners. In it there is no room for peasant family agriculture or agricultural labor, for it uses herbicides and high-tech mechanization at all levels.1

The result is already visible in statistics. Brazil is turning toward large-scale monoculture for export. A kind of agro-export re-colonization, reminiscent of the days of empire. Of the 130 million tons of grain produced, no less than 110 million tons are just soybeans and corn. In cattle production, 300 million hectares are for export production. And what's left is an immense green desert of eucalyptuses. That's the Brazilian model! It will be profitable to some landowners and a few foreign corporations. But the Brazilian people will be left with environmental liability, unemployment, and poverty.

Contradictions Emerge Rapidly

The contradictions of this perverse model come to the surface quickly. Food prices soared, as a result of financial capital's speculation at the stock exchanges and oligopolistic corporate control of the market. The dollar prices of food doubled over the past year. Food is increasingly contaminated by the intensive use of pesticides. Agribusiness fails to produce healthy food, without herbicides. Only peasant family farming succeeds in doing so. The intensive production of ethanol through sugarcane monoculture does not solve the problem of global warming -- on the contrary, it aggravates it. The biggest problem concerning fuels is not just oil -- it is, above all, the individual form of transportation promoted by financial capital to push for increased sales of cars on credit. They are transforming our cities into a hell.

This form of monoculture depletes natural resources, soil and groundwater, and affects the quality and location of water. Monoculture destroys biodiversity and upsets the environmental balance of the region.

Faced with this situation, social movements, assembled into Via Campesina of Brazil, resolved to unite and amplify their protests. In recent months, peasant protests multiplied in all states, against the model and operation of transnational corporations such as Monsanto, Cargill, Syngenta, Bunge, Bayer, etc. These protests have served as a kind of pedagogy of masses -- a warning to Brazilian society that it must wake up given the gravity of the problem and its future implications.

The Response of Businesses. . . .

Foreign corporations and their Brazilian guard dogs are aware of the social and environmental problems that they are causing. Since they don't have right on their side in the way they dominate nature, they have resolved to confront the movements of Via Campesina by combining a variety of tactics. First, million-dollar PR campaigns featuring famous artists in the press. Second, right-wing sectors' manipulation of the judiciary and the Public Ministry, which stand by them ideologically, in order to criminalize, with many prosecutions, social movement leaders and activists. And where none of these solves the problem, resort to repression, particularly in the states ruled by right-wing parties such as Río Grande Do Sul,2 São Paulo, Rio, and Minas Gerais, where the state governments do not hesitate to use the military police to violently repress the movement.

It is nothing but self-deception to believe that this type of problem can be solved with PR or repression. This is a historic conflict between two ways of producing food. One seeks only profits, even at the cost of poisoning nature and its products. The other is geared to the production of healthy food as a right of all people. There will be many battles -- that is certain.

1 For the Brazilian model of agriculture, see Via Campesina Brazil, "Queremos producir alimentos" (We Want to Produce Food), , 10 June 2008.

2 In the State of Río Grande do Sul, the Landless Workers Movement (MST) faces powerful judicial persecution: the Public Ministry has come to seek its dissolution, and several militants of social movements have been prosecuted. See Frei Betto, "Suprimir el MST o el latifundio improductivo?" (Suppress the MST or the Unproductive Latifundium?), 8 July 2008.

João Pedro Stedile is a National Coordinator of Via Campesina Brazil. The original article in Portuguese, "O capital internacional esta dominando a agricultura brasileira," was published on the Web site of the Agencia Latinoamericana de Información on 29 July 2008 and the Spanish translation "El capital internacional está dominando la agricultura" appeared on 30 July 2008. English translation by Yoshie Furuhashi.

by João Pedro Stedile

The Movement of Financial Capital

In recent years, there has been an intensive, continuous process of concentration and centralization of corporations operating and controlling the entire production process of global agriculture.

Concentration is the concept used in political economy to explain the movement of large corporations to combine, accumulate, and become large groups. Thus, in every sector of production, a situation of oligopoly is being created, with a few corporations controlling the sector. The second movement of capital is centralization, in which a single corporation comes to control several sectors of production, sometimes even the sectors unrelated to one another. These two logical movements of capital have been accompanied in the agricultural sector with a process of internationalization of control of the market and trade at the global level. In other words, some corporations have come to operate in every country and control the global market.

This dual movement of capital -- which was very much noticeable, from as far back as the theory of imperialism, in large industrial enterprises -- also came to dominate the agricultural sector in the last ten years. And what is most dangerous, now under the hegemony of financial capital, the velocity and volume of capital invested in agriculture were much faster and greater than had been the case in other productive sectors through the course of the twentieth century. That is because much capital in the form of money, i.e. financial capital, accumulated in rich countries in recent years. This capital was shifting to the purchase of shares in the most profitable corporations of the primary sector as well. Thus, in just a few years, as an effect of the investment of this financial capital in stock purchases, concentration and centralization became extraordinary.

Result

Today, almost all branches of agricultural production are controlled by groups of oligopolistic corporations, which coordinate among themselves. Thus, Cargill, Monsanto, ADM, Dreyfus, and Bunge alone are responsible for 80% of the total world production of and trade in grains such as soybeans, corn, wheat, rice, and sunflowers. Monsanto, Novartis, Bayer, and Syngenta control the entire production of transgenic seeds. In the dairy products and derivatives sector we come up against Nestlé, Dannon, and Parmalat. Here in Brazil, the entire production of raw materials for fertilizers is controlled by just three transnational corporations: Bunge, Mosaic, and Yara. Only two corporations, Monsanto and Nortox, produce glyphosate, a raw material for agricultural pesticides. AGCO, Fiat, New Holland, etc. oligopolize the agricultural machinery sector.

This movement, which had begun to develop in the 1990s, accelerated in the past two years with the crisis of capitalism in the United States. Interest rates in the core countries fell to an annual rate of 2% and, given the inflation rate, reached the point where banks would lose money. Then, financial capital shifted to the periphery of the system to protect itself from the crisis and maintain its profit rates. Over the past two years, nearly 330 billion dollars of money poured into Brazil. A part of that capital was invested through local banks, to encourage the buying of real estate, household appliances, and cars on credit, at the average annual rates of 47%. Sheer madness, compared with the rates in developed countries.

Another part of capital was destined to the purchase of lands. One report in the Folha de São Paulo newspaper estimated that foreign capital bought more than 20 million hectares in recent years, especially in the midwest regions and the new agricultural frontier of the so-called Ma-pi-to (Maranhão, Piauí, and Tocantis), where land prices were much lower. Yet another part headed to the Amazon in search of mining areas, hydroelectric projects, and possession of huge areas of biodiversity which later will bear fruit if they are exploited by their laboratories.

In the cellulose sector, three large groups -- Aracruz (Norway), Stora Enzo (Sweden-Finland), and International Paper (US) -- moved their entire production to the rich soil and climatic conditions found in Brazil. So, the expansion of eucalyptus monoculture throughout the region stretching from Bahía in the south to the Uruguay border and six new factories are being planned. Thousands of hectares of industrial eucalyptus plantations will destroy everything, creating a veritable green desert.

Likewise, there was a major investment of foreign capital in the expansion of sugarcane monoculture for ethanol production and export. The sugarcane area increased from 4 to 6 million hectares. There are 77 projects for new ethanol plants, which will be built along four major alcohol pipelines projected to transport alcohol from the midwest to the ports of Santos and Paranaguá and from the Palmas region (Tocantins State) to the port of São Luis (in Maranhão State). Two of these alcohol pipelines are owned by Petrobras and the other two will be owned by foreign investors.

Foreign capital also speeded up its investment in the production and multiplication of transgenic seeds, especially maize. Hence Syngenta, Monsanto, and Bayer are lobbying and pressuring the government to allow their varieties of GM corn. Some of these varieties are banned in Europe, but here . . . anything goes!

Agribusiness

This avalanche of foreign capital to control our agricultural production and inputs and to expand production for export was made possible only by the alliance of the aforementioned corporations and the big landowners. The landowners with large tracts of land are getting in on the action as subordinate associates of big corporations, plundering the environment, overexploiting agricultural labor, and sometimes even using slave labor.

This agricultural model, which is called agribusiness, is the marriage of transnationals and big landowners. In it there is no room for peasant family agriculture or agricultural labor, for it uses herbicides and high-tech mechanization at all levels.1

The result is already visible in statistics. Brazil is turning toward large-scale monoculture for export. A kind of agro-export re-colonization, reminiscent of the days of empire. Of the 130 million tons of grain produced, no less than 110 million tons are just soybeans and corn. In cattle production, 300 million hectares are for export production. And what's left is an immense green desert of eucalyptuses. That's the Brazilian model! It will be profitable to some landowners and a few foreign corporations. But the Brazilian people will be left with environmental liability, unemployment, and poverty.

Contradictions Emerge Rapidly

The contradictions of this perverse model come to the surface quickly. Food prices soared, as a result of financial capital's speculation at the stock exchanges and oligopolistic corporate control of the market. The dollar prices of food doubled over the past year. Food is increasingly contaminated by the intensive use of pesticides. Agribusiness fails to produce healthy food, without herbicides. Only peasant family farming succeeds in doing so. The intensive production of ethanol through sugarcane monoculture does not solve the problem of global warming -- on the contrary, it aggravates it. The biggest problem concerning fuels is not just oil -- it is, above all, the individual form of transportation promoted by financial capital to push for increased sales of cars on credit. They are transforming our cities into a hell.

This form of monoculture depletes natural resources, soil and groundwater, and affects the quality and location of water. Monoculture destroys biodiversity and upsets the environmental balance of the region.

Faced with this situation, social movements, assembled into Via Campesina of Brazil, resolved to unite and amplify their protests. In recent months, peasant protests multiplied in all states, against the model and operation of transnational corporations such as Monsanto, Cargill, Syngenta, Bunge, Bayer, etc. These protests have served as a kind of pedagogy of masses -- a warning to Brazilian society that it must wake up given the gravity of the problem and its future implications.

The Response of Businesses. . . .

Foreign corporations and their Brazilian guard dogs are aware of the social and environmental problems that they are causing. Since they don't have right on their side in the way they dominate nature, they have resolved to confront the movements of Via Campesina by combining a variety of tactics. First, million-dollar PR campaigns featuring famous artists in the press. Second, right-wing sectors' manipulation of the judiciary and the Public Ministry, which stand by them ideologically, in order to criminalize, with many prosecutions, social movement leaders and activists. And where none of these solves the problem, resort to repression, particularly in the states ruled by right-wing parties such as Río Grande Do Sul,2 São Paulo, Rio, and Minas Gerais, where the state governments do not hesitate to use the military police to violently repress the movement.

It is nothing but self-deception to believe that this type of problem can be solved with PR or repression. This is a historic conflict between two ways of producing food. One seeks only profits, even at the cost of poisoning nature and its products. The other is geared to the production of healthy food as a right of all people. There will be many battles -- that is certain.

1 For the Brazilian model of agriculture, see Via Campesina Brazil, "Queremos producir alimentos" (We Want to Produce Food), , 10 June 2008.

2 In the State of Río Grande do Sul, the Landless Workers Movement (MST) faces powerful judicial persecution: the Public Ministry has come to seek its dissolution, and several militants of social movements have been prosecuted. See Frei Betto, "Suprimir el MST o el latifundio improductivo?" (Suppress the MST or the Unproductive Latifundium?), 8 July 2008.

João Pedro Stedile is a National Coordinator of Via Campesina Brazil. The original article in Portuguese, "O capital internacional esta dominando a agricultura brasileira," was published on the Web site of the Agencia Latinoamericana de Información on 29 July 2008 and the Spanish translation "El capital internacional está dominando la agricultura" appeared on 30 July 2008. English translation by Yoshie Furuhashi.

Monday, August 11, 2008

Bolivia: Morales Wins amidst Opposition Pressure

Bolivia: Morales Wins amidst Opposition Pressure

by Franz Chávez

LA PAZ, 11 August (IPS) -- A storm of opposition broke out in Bolivia against President Evo Morales, whose mandate was resoundingly ratified by more than 63 percent of the votes in the referendum according to the consensus of exit polls broadcast by the major television networks in the country.

Bolivia has been shaken by the fiery speech of the leftist leader, who after confirming his new triumph offered to reconcile his proposed new constitution with the autonomy statutes approved in the departments of Santa Cruz, Beni, Pando, and Tarija, and the fervent rejection of his proposal by the opposition leader, Santa Cruz Governor Rubén Costas, whose mandate was also ratified.

While Morales called for unity between the departments in the west of the country, where he received the highest level of support, and the so-called "Media Luna" in the east, Costas said that the majority vote for non-ratification of the presidential mandate in this area and Chuquisaca in the south means a rejection of "dictatorship and the draft constitution that leads to confrontation among brothers."

The main square of La Paz, awash with supporters of the ruling Movement toward Socialism (MAS), roared when Morales ended his speech with the phrase coined by the Cuban Revolution "Patria o Muerte (Fatherland or Death)," the crowd shouting in response: "We will win!"

1,000 kilometers east of the seat of government, in the 24th of September Square in Santa Cruz de la Sierra, a chorus of supporters of rightist Costas repeated the word "independence" while he proclaimed the local victory against "Chavista Evoism."

With this particular expression, the followers of the leader of the Cruceño conglomerate of employers, landlords, and rightist groups, united in a conservative civic movement, are trying to tie the internal politics of Morales with his main external political ally, Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez.

The ATB television network reported that, according to the exit polls, the yes vote for ratification of the mandate of the first indigenous president of Bolivia and Vice President Álvaro García Linera added up to 63.1 percent of the total votes at all the polling stations installed on Sunday.

For its part, the Unitel television network announced a 63.52 yes vote, based on the count of the surveys from 93 percent of the polling stations.

To remove Morales and García Linera from their office, the no votes had to exceed 53.740 percent of the valid votes, which was the percentage that this slate won in the December 2005 elections. In the case of the eight governors who also put their mandates at stake on Sunday, the rejection had to be more than 50 percent to remove them.

Morales's victory is a bittersweet one, political analysts hastened to say, seeing the president with strong support in only the departments of La Paz, where his support reached 81 percent of the votes; Oruro, 81 percent; Potosí, 79 percent; and Cochabamba, 71 percent.

Instead, the voices in favor of revocation of the mandate of the leftist leaders at the helm of the government dominated in Santa Cruz, where the yes votes were only 39 percent, while they reached 43 percent in Beni, 49 percent in Pando, 47 percent in Tarija, and 46 percent in Chuquisaca, according to data from Unitel.

The preliminary count of the referendum votes on television channels, in the case of the governors, indicates that the governor of the department of La Paz, José Luis Paredes, must leave his office as 57 percent of the voters said no.

Thus the Paceños condemend the unstable behavior of this political veteran, which oscillated between independence and clear pronouncements in favor of autonomy and influential groups of the autonomist departments, on top of his style of administration characterized as corrupt by the national government.

In Cochabamba, Governor Manfred Reyes Villa also lost with disapproval of 60 percent of the electorate, among whom are coca growers who support Morales, their former trade union leader, and opponents of the administration of the rightist regional leader and former ally of President Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada (1993-1997 and 2002-2003).

The ranks of government supporters, meanwhile, lost the governorship of the Oruno department, held by Alberto Aguilar, who was rejected by 54 percent of the voters, according to preliminary data from the exit polls.

At the forefront of the victors is the rightist Costas, who obtained a 66 percent support, the result that he interpreted as support for the process of autonomy, which he heads along with the local governments of Beni, Pando, and Tarija.

With the strength of support for his mandate, Costas proclaimed the creation of an "organ of security" parallel to the police, a tax collection agency, and an office of coordination to transfer resources generated from oil to other departments, replacing the Ministry of Finance that currently fulfils this role.

Among the opposition leaders who received the most votes is Tarija Governor Mario Cossío, who ran against the forecasts portending his defeat and won a 64 percent approval.

Beni Govenor Ernesto Suárez received a 61 percent support, while his Pando counterpart Leopoldo Fernández got a 56 percent support, according to the same initial unofficial calculations.

Mario Virreina from the governing party, who runs the department of Potosí, surprised by the wide support of 75 percent he won. He is the only card that the Movement toward Socialism has at the level of local governments.

The original article in Spanish appeared on the Web site of IPS on 11 August 2008. Translation by Yoshie Furuhashi.

by Franz Chávez

LA PAZ, 11 August (IPS) -- A storm of opposition broke out in Bolivia against President Evo Morales, whose mandate was resoundingly ratified by more than 63 percent of the votes in the referendum according to the consensus of exit polls broadcast by the major television networks in the country.

Bolivia has been shaken by the fiery speech of the leftist leader, who after confirming his new triumph offered to reconcile his proposed new constitution with the autonomy statutes approved in the departments of Santa Cruz, Beni, Pando, and Tarija, and the fervent rejection of his proposal by the opposition leader, Santa Cruz Governor Rubén Costas, whose mandate was also ratified.

While Morales called for unity between the departments in the west of the country, where he received the highest level of support, and the so-called "Media Luna" in the east, Costas said that the majority vote for non-ratification of the presidential mandate in this area and Chuquisaca in the south means a rejection of "dictatorship and the draft constitution that leads to confrontation among brothers."

The main square of La Paz, awash with supporters of the ruling Movement toward Socialism (MAS), roared when Morales ended his speech with the phrase coined by the Cuban Revolution "Patria o Muerte (Fatherland or Death)," the crowd shouting in response: "We will win!"

1,000 kilometers east of the seat of government, in the 24th of September Square in Santa Cruz de la Sierra, a chorus of supporters of rightist Costas repeated the word "independence" while he proclaimed the local victory against "Chavista Evoism."

With this particular expression, the followers of the leader of the Cruceño conglomerate of employers, landlords, and rightist groups, united in a conservative civic movement, are trying to tie the internal politics of Morales with his main external political ally, Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez.

The ATB television network reported that, according to the exit polls, the yes vote for ratification of the mandate of the first indigenous president of Bolivia and Vice President Álvaro García Linera added up to 63.1 percent of the total votes at all the polling stations installed on Sunday.

For its part, the Unitel television network announced a 63.52 yes vote, based on the count of the surveys from 93 percent of the polling stations.

To remove Morales and García Linera from their office, the no votes had to exceed 53.740 percent of the valid votes, which was the percentage that this slate won in the December 2005 elections. In the case of the eight governors who also put their mandates at stake on Sunday, the rejection had to be more than 50 percent to remove them.

Morales's victory is a bittersweet one, political analysts hastened to say, seeing the president with strong support in only the departments of La Paz, where his support reached 81 percent of the votes; Oruro, 81 percent; Potosí, 79 percent; and Cochabamba, 71 percent.

Instead, the voices in favor of revocation of the mandate of the leftist leaders at the helm of the government dominated in Santa Cruz, where the yes votes were only 39 percent, while they reached 43 percent in Beni, 49 percent in Pando, 47 percent in Tarija, and 46 percent in Chuquisaca, according to data from Unitel.

The preliminary count of the referendum votes on television channels, in the case of the governors, indicates that the governor of the department of La Paz, José Luis Paredes, must leave his office as 57 percent of the voters said no.

Thus the Paceños condemend the unstable behavior of this political veteran, which oscillated between independence and clear pronouncements in favor of autonomy and influential groups of the autonomist departments, on top of his style of administration characterized as corrupt by the national government.

In Cochabamba, Governor Manfred Reyes Villa also lost with disapproval of 60 percent of the electorate, among whom are coca growers who support Morales, their former trade union leader, and opponents of the administration of the rightist regional leader and former ally of President Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada (1993-1997 and 2002-2003).

The ranks of government supporters, meanwhile, lost the governorship of the Oruno department, held by Alberto Aguilar, who was rejected by 54 percent of the voters, according to preliminary data from the exit polls.

At the forefront of the victors is the rightist Costas, who obtained a 66 percent support, the result that he interpreted as support for the process of autonomy, which he heads along with the local governments of Beni, Pando, and Tarija.

With the strength of support for his mandate, Costas proclaimed the creation of an "organ of security" parallel to the police, a tax collection agency, and an office of coordination to transfer resources generated from oil to other departments, replacing the Ministry of Finance that currently fulfils this role.

Among the opposition leaders who received the most votes is Tarija Governor Mario Cossío, who ran against the forecasts portending his defeat and won a 64 percent approval.

Beni Govenor Ernesto Suárez received a 61 percent support, while his Pando counterpart Leopoldo Fernández got a 56 percent support, according to the same initial unofficial calculations.

Mario Virreina from the governing party, who runs the department of Potosí, surprised by the wide support of 75 percent he won. He is the only card that the Movement toward Socialism has at the level of local governments.

The original article in Spanish appeared on the Web site of IPS on 11 August 2008. Translation by Yoshie Furuhashi.

Sunday, August 10, 2008

Exit Polls: Morales Ratified by Larger Margin than in 2005

Exit Polls: Morales Ratified by Larger Margin than in 2005

by TeleSUR

The exit poll results ratified the mandate of President Morales and his Vice President García Linera and recalled three of the eight governors who were subjected to voting at the referendum.

Another survey by the Captura Consulting Group also gives victory to Morales and García Linera, though with 60 percent versus 40 percent, with a margin of error of 5 percent.

If this trend holds, the Morales-García Linera duo will have earned more than 7 percentage points above 53.7 percent that they needed, which was what they won in the presidential election of December 2005.

ATB, a private channel, noted that the president won 56.7 percent of the votes in his favor.

In the exit poll results of the recall of governors, José Luis Paredes, the opposition governor of La Paz (west), was recalled by 60 percent of the voters voting no, against 40 percent voting yes.

Manfred Reyes, the opposition governor of Cochabamba (center), was also recalled from office by a 40 percent yes vote versus a 60 percent no vote.

Mario Cossio, the governor of Tarija (south), won 65 percent of the votes, against 35 percent voting no, in the referendum, confirming him in his office.

Mario Virreira, the governor of Potosí (south), won 77 percent of the votes, against a 33 percent no vote, which ratifies his mandate as governor of this department.

Ernesto Suárez, the governor of Beni (North), won 72 percent of the votes, with 28 percent voting no, which ratifies his mandate as governor of this department.

Leopoldo Fernández, the governor of Pando (north), won a 59 percent yes vote, against a 41 percent no vote, thus also confirmed in office.

Rubén Costas, the governor of Santa Cruz (east), was confirmed in office by 79 percent voting yes, against 21 percent voting no.

Alberto Aguilar, the governor of Oruro (southwest), from the ruling party Movement for Socialism (MAS), obtained a 42 percent yes vote against a 58 percent no vote, which revokes his mandate.

The TeleSur special correspondent to La Paz, Patricia Villegas, said that the first official report of the National Electoral Court (CNE) will come at 20:00 local time (00:00 UTC).

The original report in Spanish was published on the Web site of TeleSUR on 10 August 2008. Translation by Yoshie Furuhashi.

by TeleSUR

The exit poll results ratified the mandate of President Morales and his Vice President García Linera and recalled three of the eight governors who were subjected to voting at the referendum.

The exit poll results published by TV Bolivia give victory to Morales and García Linera with 61 percent of the votes. (Photo: TeleSUR)

Another survey by the Captura Consulting Group also gives victory to Morales and García Linera, though with 60 percent versus 40 percent, with a margin of error of 5 percent.

If this trend holds, the Morales-García Linera duo will have earned more than 7 percentage points above 53.7 percent that they needed, which was what they won in the presidential election of December 2005.

ATB, a private channel, noted that the president won 56.7 percent of the votes in his favor.

In the exit poll results of the recall of governors, José Luis Paredes, the opposition governor of La Paz (west), was recalled by 60 percent of the voters voting no, against 40 percent voting yes.

Manfred Reyes, the opposition governor of Cochabamba (center), was also recalled from office by a 40 percent yes vote versus a 60 percent no vote.

Mario Cossio, the governor of Tarija (south), won 65 percent of the votes, against 35 percent voting no, in the referendum, confirming him in his office.

Mario Virreira, the governor of Potosí (south), won 77 percent of the votes, against a 33 percent no vote, which ratifies his mandate as governor of this department.

Ernesto Suárez, the governor of Beni (North), won 72 percent of the votes, with 28 percent voting no, which ratifies his mandate as governor of this department.

Leopoldo Fernández, the governor of Pando (north), won a 59 percent yes vote, against a 41 percent no vote, thus also confirmed in office.

Rubén Costas, the governor of Santa Cruz (east), was confirmed in office by 79 percent voting yes, against 21 percent voting no.

Alberto Aguilar, the governor of Oruro (southwest), from the ruling party Movement for Socialism (MAS), obtained a 42 percent yes vote against a 58 percent no vote, which revokes his mandate.

The TeleSur special correspondent to La Paz, Patricia Villegas, said that the first official report of the National Electoral Court (CNE) will come at 20:00 local time (00:00 UTC).

Bolivia: Evo Morales Gano Referendo Presidencial

The original report in Spanish was published on the Web site of TeleSUR on 10 August 2008. Translation by Yoshie Furuhashi.

Mahmoud Darwish

Celebrated Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish died on 9 August 2008, at the age of 67, after open-heart surgery. Here is a video of his most famous poem "Identity Card" (published in 1964):

A poet of exile par excellence, Darwish died in exile. The village of his birth in western Galilee, al-Birwa (whose Arabic name is said to have been first recorded in Persian poet and traveler Nasser Khosro's Safarnameh), had been demolished, in whose place Moshav Ahihud was built in 1950.

Simone Bitton's 1997 documentary film Mahmoud Darwich: As the Land Is the Language traces some of the paths of Darwish's exile.

A poet of exile par excellence, Darwish died in exile. The village of his birth in western Galilee, al-Birwa (whose Arabic name is said to have been first recorded in Persian poet and traveler Nasser Khosro's Safarnameh), had been demolished, in whose place Moshav Ahihud was built in 1950.

Simone Bitton's 1997 documentary film Mahmoud Darwich: As the Land Is the Language traces some of the paths of Darwish's exile.

Mahmoud Darwich, et la terre comme la langue

Saturday, August 09, 2008

Memory of Fire: Bringing Embers of Hiroshima to Cuba

Memory of Fire:

Bringing Embers of Hiroshima to Cuba

Che headed the Cuban delegation to Asia and Africa in 1959. During the delegation's visit to Japan, Che requested that they be allowed to go to Hiroshima, the requested turned down by the Japanese government on the grounds that it wasn't listed on the delegation's itinerary. (Omar Fernández, who was with Guevara on the delegation, wonders if the denial wasn't actually due to Tokyo's desire not to call attention to the US war crimes.1) Undaunted, Che, with two other delegates, jumped on a night train and visited Hiroshima on 25 July 1959 without telling the Japanese government. What Che saw, some of which was published in his article "Recuperase Japón de la tragedia atomica" (Verde Olivo, 19 October 1959), became part of the Cuban memory of Hiroshima.

Che also strongly recommended that Fidel Castro himself visit Hiroshima, which Fidel did in 2003. Fidel's 2003 visit, too, is part of this fascinating documentary.

In May this year, Atena Japan, together with other activist NGOs, brought Aleida Guevara to Japan, to celebrate "小さな国の大きな奇跡" (A Little Country Working Great Miracles). The people of Japan have much to learn from Cuban environmentalism as they confront their government bent on becoming a plutonium superpower.2

Notes

1 Former Defense Minister of Japan Kyuma Fumio memorably said in 2007 that the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were "shoganai" (couldn't have been helped), for the bombings were "necessary" to end the war before a Soviet invasion of Japan!

2 Gavan McCormack, "Japan as a Nuclear State" (Japan Focus, 1 August 2007); "Japan as a Plutonium Superpower" (Japan Focus, 9 December 2007); and "August Nuclear Thoughts: the New Proliferation" (Japan Focus, 4 August 2008).

Bringing Embers of Hiroshima to Cuba

炎の記憶

原爆の残り火をキューバへ

Che headed the Cuban delegation to Asia and Africa in 1959. During the delegation's visit to Japan, Che requested that they be allowed to go to Hiroshima, the requested turned down by the Japanese government on the grounds that it wasn't listed on the delegation's itinerary. (Omar Fernández, who was with Guevara on the delegation, wonders if the denial wasn't actually due to Tokyo's desire not to call attention to the US war crimes.1) Undaunted, Che, with two other delegates, jumped on a night train and visited Hiroshima on 25 July 1959 without telling the Japanese government. What Che saw, some of which was published in his article "Recuperase Japón de la tragedia atomica" (Verde Olivo, 19 October 1959), became part of the Cuban memory of Hiroshima.

Che also strongly recommended that Fidel Castro himself visit Hiroshima, which Fidel did in 2003. Fidel's 2003 visit, too, is part of this fascinating documentary.

In May this year, Atena Japan, together with other activist NGOs, brought Aleida Guevara to Japan, to celebrate "小さな国の大きな奇跡" (A Little Country Working Great Miracles). The people of Japan have much to learn from Cuban environmentalism as they confront their government bent on becoming a plutonium superpower.2

Notes

1 Former Defense Minister of Japan Kyuma Fumio memorably said in 2007 that the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were "shoganai" (couldn't have been helped), for the bombings were "necessary" to end the war before a Soviet invasion of Japan!

久間防衛相の『原爆しょうがない』発言部分の映像

2 Gavan McCormack, "Japan as a Nuclear State" (Japan Focus, 1 August 2007); "Japan as a Plutonium Superpower" (Japan Focus, 9 December 2007); and "August Nuclear Thoughts: the New Proliferation" (Japan Focus, 4 August 2008).

Friday, August 08, 2008

Ossetians: Their Language and Identity

Ambrose Bierce said that war is God's way of teaching Americans geography. It can also teach ethnolinguistics. As Georgia attacked the Ossetians and Russian peacekeepers,1 I looked for background information and found out that the Ossetians speak an Iranian language, divided into two dialects Iron and Digor. Here's a paper that includes a long section on a fascinating history of construction of the Ossetian identity: Victor Shnirelman, "The Politics of a Name: Between Consolidation and Separation in the Northern Caucasus," Acta Slavica Iaponica, Tomus 23, pp. 37-73.

1 Predictably, the United States and Europe sided with Georgia at the UN Security Council today, at the cost of preventing an immediate ceasefire:

1 Predictably, the United States and Europe sided with Georgia at the UN Security Council today, at the cost of preventing an immediate ceasefire:

The U.N. Security Council failed on Friday to reach an agreement on a Russian-drafted statement that would have called on Georgia and separatists in its South Ossetia region to immediately halt all bloodshed.Georgia is an important energy transit state, whose two major pipelines, Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan and Baku-Tbilisi-Erzurum, are "particularly valued by the European Union because they reduce dependency on Russian supplies and do not cross Russian territory" ("Georgia's Importance as an Energy Transit State," Reuters, 8 August 2008).

The 15 Security Council members began meeting late on Thursday and remained behind closed doors for two hours until early Friday morning to discuss the three-sentence statement.

But council diplomats said one phrase in it was unacceptable to the Georgians, backed by the United States and Europeans. That wording called on all sides in the conflict "to renounce the use of force," according to a draft of the text.

After failing to agree, the council decided not to take any action on the issue, the diplomats said. (Louis Charbonneau, "UN Council Split on South Ossetia, Russia Angry," Reuters, 8 August 2008)

Thursday, August 07, 2008

Light at the End of the Tunnel

A joke that is making the rounds via email:

Due to Recent Budget Cuts and

the Rising Energy Costs,

the Light at End of the Tunnel Has Been Turned Off.

We Apologize for the Inconvenience.

Sunday, August 03, 2008

Why the World Isn't Flat

Why the World Isn't Flat

by Ha-Joon Chang

Let me start my talk with a little story. In 1958, Japan tried to export this first passenger car to the US market. The company was Toyota, the car was called Toyopet. And, as you can guess from the name, it was a very cheap, small subcompact car, more of a four-wheels-and-an-ashtray kind of thing, which Toyota hoped rich American consumers could pick up as an afterthought, after finishing their grocery shopping with the changes left. Unfortunately, it was a total flop, so much so that Toyota actually had to withdraw the product. In the realm of failures, this is, like, the biggest thing. It's not just not selling well -- it had to be withdrawn from the market.

This provoked a very heated debate in Japan. The free trade economists centered around the Bank of Japan, the central bank, said, "Look, this is what happens when you go against the theory of comparative advantage. In a country like Japan, which in relative terms has lots of labor and little capital, we shouldn't be producing things like motor cars, which are very capital-intensive in production." Of course, at that time, Japan's biggest export item was silk. So, case proven, already. And they said, "Don't tell us that you couldn't succeed because you didn't have help. You had 25 years of very high tariff protection. We kicked out all the foreign car makers 20 years ago and didn't let any of them in since then. And back in 1949 this central bank even injected public money into Toyota to save it from bankruptcy. So, please don't tell us that you couldn't succeed because you didn't have help, because you had all the help you can ask for."

You know, today, it sounds strange that the Japanese were debating whether to keep producing motor cars. It's a little like the French having national debate on whether to discontinue wine production or the Scotts deciding whether to do away with the smoked salmon industry. But if you went back in time and thought about this from the vantage point of view of 1958, actually I think the free trade economists made more sense. What was Japan? I mean, Japan's income was basically at the same level as that of South Africa and Argentina. In 1961, as late as 1961, Japan's per capita income was $402 in current terms, and Chile's income was $378. It was a very poor country, whose main export item was silk. Well, luckily for Japan, and I'd say for the rest of the world, which subsequently benefited from efficient Japanese cars, the protectionists won the day, and the Japanese government continued with the support for the industry, and, as you know, the rest is history. So, when you meet a free trade economist next time, ask him what car he drives. If he drives a Toyota or for that matter any other Japanese car, he doesn't know what he's talking about, OK?

Now, it gets better, because the ironic thing is that, half a century after the Toyota debacle, Toyota's luxury brand Lexus has become something of an icon for free market globalization thanks to the American journalist Thomas Friedman. Some of you at least must have read this book The Lexus and the Olive Tree. Quite a wacky title. I mean, I like wacky titles, so no problem there, but, for those who haven't read this book, the title remains a complete mystery, so let me explain why he calls it that. At the beginning of this book, he says: I went to Japan in 1993 or somewhere around that time, and I went to visit a Toyota factory that manufactures their luxury brand Lexus, and I was bowled over -- this factory was so efficient, so clean, so quiet, so everything . . . I saw the future. And he continues: on my way back from the factory to my hotel in Tokyo, riding on a famous Japanese Shinkansen bullet train, eating my sushi bento lunch, I was reading the International Herald Tribune and came across yet another article about killings in the Middle East. And he has an epiphany, you know. He says: then it really hit me -- half the world is either making things like a Lexus or at least trying to earn money to buy things like a Lexus . . . and the other half is stuck in the past. These people in the Middle East are fighting over who owns which olive tree. These people should wake up -- there's a whole new world out there.

Well, to be fair to him, he says that this olive tree world could exist with the Lexus world in the same country, in the same person, and so on and so forth . . . I don't want to be unfair to him, but basically his message is that these countries who live in the olive tree world need to wake up, put on what he calls the Golden Straightjacket, basically a set of pro-market, neoliberal policies, made up of tough control on government spending and inflation, liberalization in trade and investment, privatization of state-owned industries and state pensions and so on. And he says that this is the only way to survive. I'm sorry if this Golden Straightjacket isn't comfortable, but unfortunately this is the only model that is available in this historical season. . . .

Now, the crazy thing is, go back to the earlier Toyopet example, when you think about that, basically, if Japan had followed Friedman's kind of advice in the 1950s and 1960s, the Japanese would not be exporting the Lexus, because Toyota probably would have been either wiped out or more likely taken over by General Motors and made into some secondary producer. They won't be exporting the Lexus but they will be still fighting over who owns which mulberry tree, the tree that feeds silkworms. You know, this is so crazy: it's like someone writing a book on self-made men, and the first chapter is Henry Ford II.

Ha-Joon Chang is a reader in the political economy of development at the University of Cambridge and a senior research associate at the Center for Economic and Policy Research. He is the author of Bad Samaritans: The Myth of Free Trade and the Secret History of Capitalism (2007) and Kicking Away the Ladder: Development Strategy in Historical Perspective (2002) among numerous other publications. The video was produced by the New America Foundation. The text above is a partial transcript of Chang's lecture.

by Ha-Joon Chang

Let me start my talk with a little story. In 1958, Japan tried to export this first passenger car to the US market. The company was Toyota, the car was called Toyopet. And, as you can guess from the name, it was a very cheap, small subcompact car, more of a four-wheels-and-an-ashtray kind of thing, which Toyota hoped rich American consumers could pick up as an afterthought, after finishing their grocery shopping with the changes left. Unfortunately, it was a total flop, so much so that Toyota actually had to withdraw the product. In the realm of failures, this is, like, the biggest thing. It's not just not selling well -- it had to be withdrawn from the market.

This provoked a very heated debate in Japan. The free trade economists centered around the Bank of Japan, the central bank, said, "Look, this is what happens when you go against the theory of comparative advantage. In a country like Japan, which in relative terms has lots of labor and little capital, we shouldn't be producing things like motor cars, which are very capital-intensive in production." Of course, at that time, Japan's biggest export item was silk. So, case proven, already. And they said, "Don't tell us that you couldn't succeed because you didn't have help. You had 25 years of very high tariff protection. We kicked out all the foreign car makers 20 years ago and didn't let any of them in since then. And back in 1949 this central bank even injected public money into Toyota to save it from bankruptcy. So, please don't tell us that you couldn't succeed because you didn't have help, because you had all the help you can ask for."

You know, today, it sounds strange that the Japanese were debating whether to keep producing motor cars. It's a little like the French having national debate on whether to discontinue wine production or the Scotts deciding whether to do away with the smoked salmon industry. But if you went back in time and thought about this from the vantage point of view of 1958, actually I think the free trade economists made more sense. What was Japan? I mean, Japan's income was basically at the same level as that of South Africa and Argentina. In 1961, as late as 1961, Japan's per capita income was $402 in current terms, and Chile's income was $378. It was a very poor country, whose main export item was silk. Well, luckily for Japan, and I'd say for the rest of the world, which subsequently benefited from efficient Japanese cars, the protectionists won the day, and the Japanese government continued with the support for the industry, and, as you know, the rest is history. So, when you meet a free trade economist next time, ask him what car he drives. If he drives a Toyota or for that matter any other Japanese car, he doesn't know what he's talking about, OK?