Thomas Bleha, a former U.S. Foreign Service officer in Japan, has a fascinating piece in the May-June issue of Foreign Affairs that begins like this: "In the first three years of the Bush administration, the United States dropped from 4th to 13th place in global rankings of broadband Internet usage. Today, most U.S. homes can access only 'basic' broadband, among the slowest, most expensive and least reliable in the developed world, and the United States has fallen even further behind in mobile-phone-based Internet access. The lag is arguably the result of the Bush administration's failure to make a priority of developing these networks. In fact, the United States is the only industrialized state without an explicit national policy for promoting broadband."To say that the United States lacks "an explicit national policy for promoting broadband" (Bleha qtd. in Friedman, 15 Apr. 2005) understates the problem for Americans on the wrong side of the digital divide. A number of cities and towns are actually building cheaper alternatives to oligopolistic Internet Service Providers that charge monthly broadband fees of $50 and above, often choosing free wireless access like Dayton and Philadelphia. Communications giants, however, are doing all they can to block such public access efforts:

. . . In 2001, Japan was well behind the United States in the broadband race. But thanks to top-level political leadership and ambitious goals, it soon began to move ahead.

"By May 2003, a higher percentage of homes in Japan than the United States had broadband. . . .

"Today, nearly all Japanese have access to 'high-speed' broadband, with an average connection time 16 times faster than in the United States - for only about $22 a month. . . ." ("Bush Disarms, Unilaterally," New York Times 15 Apr. 2005)

You’ll be pleased to know that communism was defeated in Pennsylvania last year. Governor Ed Rendell signed into law a bill prohibiting the Reds in local government from offering free Wi-Fi throughout their municipalities. The action came after Philadelphia, where more than 50 percent of neighborhoods don’t have access to broadband, embarked on a $10 million wireless Internet project. City leaders had stepped in where the free market had failed. Of course, it’s a slippery slope from free Internet access to Karl Marx. So Rendell, the telecom industry’s latest toady, even while exempting the City of Brotherly Love, acted to spare Pennsylvania from this grave threat to its economic freedom.Legislation that prohibits public broadband access is pending in Colorado, Florida, Illinois, Iowa, Nebraska, Ohio, Oregon, Tennessee, and Texas. Indiana, however, defeated HB 1148, "championed by SBC Communication," which "would have prohibited Indiana cities and towns from providing municipal broadband services" ("Community Internet: Indiana" Freepress.net). That shows that media democracy activists have a fighting chance.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . Pushed by lobbyists, at least 14 states have passed legislation similar to Pennsylvania's. I've always wondered what almost $1 billion spent on lobbying state lawmakers gets you. Now I'm beginning to see. (Lawrence Lessig, "Why Your Broadband Sucks," Wired 13.3 March 2005)

After all, who aside from telecom giants would benefit from their rent-seeking? What's good for AOL, SBC, Verizon, and the like isn't good for America, not even American capitalists as a whole.

In the same issue of the New York Times where Friedman lamented "an industrial-age presidency, catering to a pre-industrial ideological base, in a post-industrial era" (Friedman, 15 Apr. 2005), Paul Krugman had this to say about health care costs in the United States:

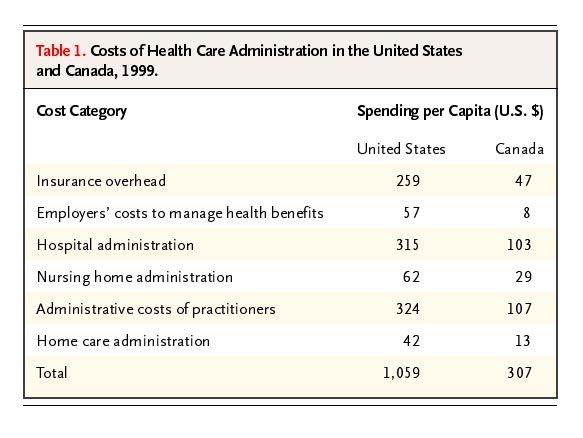

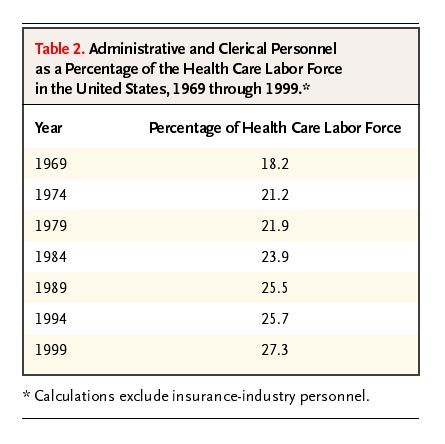

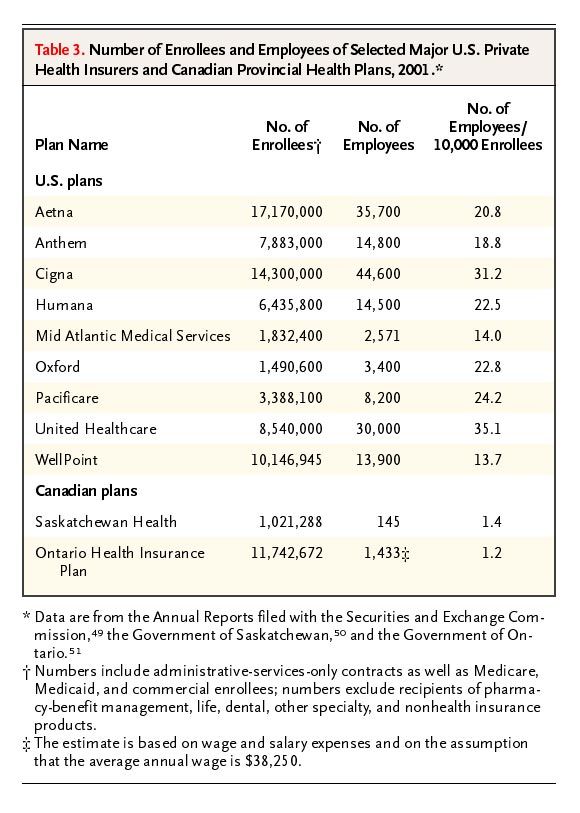

In 2002, the latest year for which comparable data are available, the United States spent $5,267 on health care for each man, woman and child in the population. Of this, $2,364, or 45 percent, was government spending, mainly on Medicare and Medicaid. Canada spent $2,931 per person, of which $2,048 came from the government. France spent $2,736 per person, of which $2,080 was government spending.Here are a few graphic illustrations that Woolhandler, Campbell, and Himmelstein provide:

Amazing, isn't it? U.S. health care is so expensive that our government spends more on health care than the governments of other advanced countries, even though the private sector pays a far higher share of the bills than anywhere else.

What do we get for all that money? Not much.

Most Americans probably don't know that we have substantially lower life-expectancy and higher infant-mortality figures than other advanced countries. It would be wrong to jump to the conclusion that this poor performance is entirely the result of a defective health care system; social factors, notably America's high poverty rate, surely play a role. Still, it seems puzzling that we spend so much, with so little return.

A 2003 study published in Health Affairs [22.3, May/June 2003] (one of whose authors is my Princeton colleague Uwe Reinhardt) tried to resolve that puzzle by comparing a number of measures of health services across the advanced world. What the authors found was that the United States scores high on high-tech services -- we have lots of M.R.I.'s -- but on more prosaic measures, like the number of doctors' visits and number of days spent in hospitals, America is only average, or even below average. There's also direct evidence that identical procedures cost far more in the U.S. than in other advanced countries.

The authors concluded that Americans spend far more on health care than their counterparts abroad -- but they don't actually receive more care. The title of their article? "It's the Prices, Stupid."

Why is the price of U.S. health care so high? One answer is doctors' salaries: although average wages in France and the United States are similar, American doctors are paid much more than their French counterparts. Another answer is that America's health care system drives a poor bargain with the pharmaceutical industry.

Above all, a large part of America's health care spending goes into paperwork. A 2003 study ["Costs of Health Care Administration in the United States and Canada" by Steffie Woolhandler, M.D., M.P.H., Terry Campbell, M.H.A., and David U. Himmelstein, M.D. ] in The New England Journal of Medicine [349.8, 21 Aug. 2003] estimated that administrative costs took 31 cents out of every dollar the United States spent on health care, compared with only 17 cents in Canada. (Paul Krugman, "The Medical Money Pit," New York Times 15 Apr. 2005)

("Costs of Health Care Administration in the United States and Canada," New England Journal of Medicine 349.8, 21 Aug. 2003)

General Motors Corp.'s bonds fell after the company failed to wrest any concessions from its largest trade union, adding to concern the world's biggest automaker won't be able to cut health-care costs.GM, as well as other US manufacturers, succeed in extracting big and small concessions from unionized workers from time to time, but privatized health care still puts them at a disadvantage when competing with corporations that have socialized the costs of their employees' health care. Shouldn't that motivate them to join hands with organized labor and advocate socialized medicine, which is bound to lower their health care bills dramatically even if they end up paying slightly higher taxes?

GM . . . agreed with the United Auto Workers union to stay within the bounds of their four-year contract as the company seeks to restrain health costs that have risen 33 percent in five years. The company's stock fell 6.5 percent to its lowest level since 1993 during trading in New York yesterday. (John Glover, "GM Bonds Plunge; Union Won't Reopen Health Contract [Update2]," Bloomberg.com 15 Apr. 2005)

Large employers are indeed looking for a cheaper alternative to the status quo, but "[i]n considering new strategies, employers rely on their view that a market-driven system can best address the widely recognized inefficiency and suboptimal quality of our current health care system.2-4 They believe that the same approach that has worked in other parts of their business -- providing financial incentives to improve quality and lower costs -- can be adapted to health care" ("Large Employers' New Strategies in Health Care," New England Journal of Medicine 347.12, 19 Sep. 2002, p. 939). Apparently, either ideology gets in the way of seeing a proven solution that is staring US manufacturers in their face, or US manufacturers have concluded that, if all else fails, they can always offshore almost all jobs.

Universal access, whether in providing broadband or health care, is far more efficient than privatized access. Not only would it benefit workers and small businesses greatly; it would also achieve considerable cost savings for big corporations. Corporate America doesn't see it this way, though. The ruling class are evidently more class conscious than the working class in the United States, and capitalists who own and manage big corporations would rather exercise class solidarity with small factions of their class: those who own telecom giants in the case of broadband and those who own insurance companies and HMOs in the case of health care. Therefore, it falls to American workers to save themselves. If they do, they may, just as in the times of the Great Depression, ironically end up saving American capitalism from American capitalists.

No comments:

Post a Comment