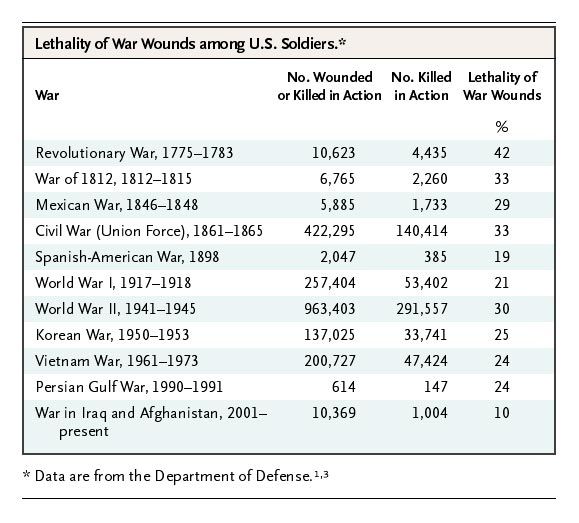

Though firepower has increased, lethality has decreased. In World War II, 30 percent of the Americans injured in combat died.3 In Vietnam, the proportion dropped to 24 percent. In the war in Iraq and Afghanistan, about 10 percent of those injured have died. At least as many U.S. soldiers have been injured in combat in this war as in the Revolutionary War, the War of 1812, or the first five years of the Vietnam conflict, from 1961 through 1965 (see table). This can no longer be described as a small or contained conflict. But a far larger proportion of soldiers are surviving their injuries.Adjusted for improvement in battle care, scale of deployment, and character of war, Phillip Carter and Owen West argue, "infantry duty in Iraq circa 2004 comes out just as intense as infantry duty in Vietnam circa 1966 -- and in some cases more lethal":

(Atul Gawande, "Casualties of War: Military Care for the Wounded from Iraq and Afghanistan," New England Journal of Medicine 351.24, December 9, 2004)

In 1966, for example, 5,008 U.S. servicemen were killed in action in Vietnam. Another 1,045 died of "non-hostile" wounds (17 percent of the total fatalities). Since Jan. 1, 2004, 754 U.S. servicemen and -women have been killed in action in Iraq, and 142 more soldiers died in "non-hostile" mishaps (16 percent of the fatalities, similar to Vietnam). Applying Vietnam's lethality rate (25 percent) to the total number of soldiers killed in action in Iraq this year, however, brings the 2004 KIA total to 1,131.Carter and West find the comparison between Hue and Falluja especially illuminating: in Hue, "three Marine battalions (roughly 3,000 men)" fought 12.000 Vietnamese in 1968, and "147 Marines were killed and 857 wounded"; in Falluja, three Marine battalions attacked several thousand Iraqis in 2004, and "more than 104 soldiers and Marines have been killed and more than 1,100 wounded" (December 27, 2004).

The scale can be further balanced. In 1966, U.S. troops in Vietnam numbered 385,000. In 2004, the figure in Iraq has averaged roughly 142,000. Comparing the burden shouldered by individual soldiers in both conflicts raises the 2004 "constant casualty" figure in Iraq to 3,065 KIA. Further, casualties in Iraq fall more heavily on those performing infantry missions. Riflemen -- as well as tankers and artillerymen who operate in provisional infantry units in Iraq -- bear a much higher proportion of the risk than they did in Vietnam. In Vietnam, helicopter pilots and their crews accounted for nearly 5 percent of those killed in action. In Iraq in 2004, this figure was less than 3 percent. In Vietnam, jet pilots accounted for nearly 4 percent of U.S. KIAs. In 2004, the United States did not lose a single jet to enemy action in Iraq. When pilots and aircrews are removed from the equation, 4,602 ground-based soldiers died during 1966 in Vietnam, compared to 2,975 in Iraq during 2004. ("Iraq 2004 Looks Like Vietnam 1966," Slate, December 27, 2004)

Some would argue that soldiers in today's volunteer military would more stoically bear the same high casualty rate than conscripts during the Vietnam War, but is the difference between them so clear? Carter and West remind us that "[v]olunteers outnumbered conscripts by a 9-1 ratio in the units that saw combat during the war's early days in 1966" (emphasis added, December 27, 2004). Altogether during the Vietnam War, "1,728,344 men were drafted. Of the forces who actually served in Vietnam, 648,500 (25%) were draftees. Draftees (17,725) accounted for 30.4% of combat deaths in Vietnam" (emphasis added, "The Draft and Historical Amnesia," VFW Magazine, March, 2003). In short, conscripts were a minority. In the current war, "[in] recent months, at any given moment, the stop-loss policy has affected about 7,000 soldiers who had been planning to retire, leave the military or move to a different military job" (Monica Davey, "Eight Soldiers Plan to Sue Over Army’s Stop-Loss Policy," New York Times, December 6, 2004), turning a significant minority of regular troops into conscripts in effect. Moreover, National Guard and Army Reserve soldiers, who cannot be expected to perform long and frequent overseas deployments without turning their civilian lives upside down, "now make up nearly 40 percent of the 148,000 troops in Iraq" (Eric Schmitt, "Guard Reports Serious Drop in Enlistment," New York Times, December 18, 2004).

Anger and discontent in the Army and Reserve rank and file today may very well be more widely spread than they were among rank-and-file soldiers in 1966. Pluralities of "commissioned officers and their families" (43%), "non-commissioned officers and their families" (41%), and "junior enlisted personnel [ranks E-4 and below]" (44%) think that the National Guard and Reserve forces sent to Iraq were not "properly trained and equipped for service there" (Adam Clymer/Annenberg Public Policy Center, "Service Members, Families Say Pentagon Sent Too Few Troops to Iraq, Stressed National Guard and Reserves, Should Allow Photos of Coffins at Dover, Annenberg Data Show," October 16, 2004, Table B, p. 7). Asked whether they think "the U.S. should keep military troops in Iraq until a stable government is established there" or "the U.S. should bring its troops home as soon as possible," 31% of junior enlisted personnel said, "Bring Troops Home," and a whopping 47% of them believe that it is not the proper thing for the Pentagon to order "some people in the military to stay on active duty beyond the time their enlistment expired" (Clymer/Annenberg Public Policy Center, October 16, 2004, Table B, p. 7).

Washington has not only not won the hearts and minds of Iraqis; it has lost the hearts and minds of a sizable number of US soldiers, and the losses have begun to show. On October 13, 2004, soldiers from the 343rd Quartermaster Company refused to go on a convoy mission to "drive fuel and water trucks from Tallil Air Base, their home in southern Iraq, to Taji, a base north of Baghdad" because their trucks were not sufficiently armored -- an act that could be considered a mutiny punishable by death or prison -- but none of them will face a court-martial (Ron Jensen, "Soldiers Who Refused Convoy Mission Won't be Required to Face Court-Martial," Stars and Stripes, December 7, 2004). If court-martialed and found guilty of refusing to obey an order, they could have been "sentenced to up to two years in jail," but the brass decided that all they could do to them was to mete out "'non-judicial' punishment under Article 15 of the U.S. military justice code," which gives commanders "discretion to order brief detention of up to a month, loss of up to a month's pay, extra duties and loss of rank" (Reuters, "Minor Sanctions for U.S. Troops Who Balked in Iraq," December 6, 2004). Why? The Army admits that the refusers "raised a valid concern," and it also knows that other soldiers and their families are behind them:

The group received an outpouring of support from family in the States and from some stationed in Iraq and Kuwait.Then, "[o]n December 6, 2004, eight U.S. soldiers -- five stationed in Iraq, two in Kuwait on their way to Iraq, and one home on leave from Iraq about to be shipped back -- filed a federal lawsuit challenging the Armed Services’ so-called "stop loss" policy," supported by the Center for Constitutional Rights ("Eight Soldiers Sue U.S. over "Stop-Loss" Policy"). Given the aforementioned survey results, I am certain that the eight soldiers' lawsuit is one that nearly half of the rank and file support and that all in the military are carefully watching.

"There are troops who support you and believe you did the right thing," one soldier in Kuwait in had said in Stars and Stripes. "You took a stand, not just for yourselves, but for every member of the military." (Jensen, December 7, 2004)

Last not the least, the Army National Guard fell "30 percent below its recruiting goals" (Schmitt, December 18, 2004).

The Pentagon has learned a lesson from the Vietnam War and wishes to avoid the draft. The Pentagon's draft evasion, however, may turn out to be as destructive of morale and discipline as the draft itself.

No comments:

Post a Comment