Since

the landslide electoral victory of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, the George W. Bush administration's propaganda machine has already gotten into high gear. All manner of allegations made by Iranian exiles (e.g., Louis Charbonneau, "Austrian Makes New Charge against Iran President-elect,"

Reuters,

2 Jul. 2005)

* and ex-hostages in the US Embassy seizure (e.g., Brian Knowlton, "Iranians Deny Leader Is Tied to Hostage Standoff,"

New York Times,

30 Jun. 2005) have surfaced.

Thankfully, intelligence agencies, burned by the Iraq War, appear to be putting a brake on the Bush administration -- for the time being.

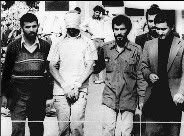

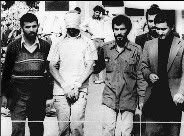

U.S. investigators have concluded that Iranian president-elect Mahmoud Ahmadinejad is not the glowering Islamic militant seen escorting an American hostage in a 1979 photograph that was widely publicized this week, officials said Friday.

U.S. investigators have concluded that Iranian president-elect Mahmoud Ahmadinejad is not the glowering Islamic militant seen escorting an American hostage in a 1979 photograph that was widely publicized this week, officials said Friday.

The conclusion casts doubt on what had been considered a key piece of evidence indicating that Iran's new president was among the leaders of the group of students who seized control of the U.S. Embassy in Tehran and went on to hold dozens of Americans hostage for 444 days.

A U.S. official familiar with the investigation of Ahmadinejad's role said that analysts had found "serious discrepancies" between the figure in the 1979 photo and other images of the Iranian president-elect. The discrepancies included differences in facial structure and features, the official said.

If there is a case to be made that Ahmadinejad was among the hostage takers in 1979, the official said, "it doesn't look as if it will be done on the basis of those photographs." (Greg Miller, "U.S.: Photo Not of Iran Chief," Los Angeles Times, 2 Jul. 2005)

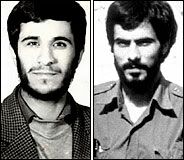

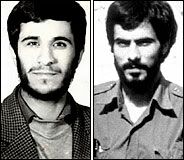

The ex-hostages' allegations led Iran to release a photograph of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, circa 1979 (Knowlton,

30 Jun. 2005). The young man on the left, Ahmadinejad around 1979, bears no resemblance to the hostage taker on the right (except in the eye of a racist to whom all Iranians look alike).

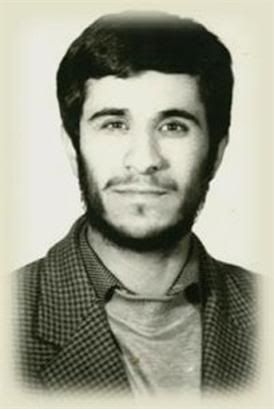

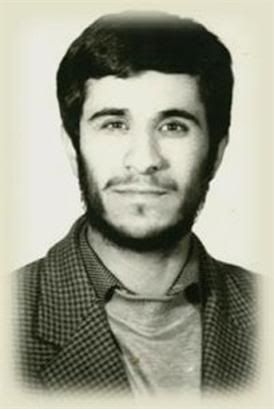

Here is a larger image of the same photograph of Ahmadinejad. In the 1979 photograph, Ahmadinejad, then 22 or 23, looks not like a theocratic bully but like a delicate Ernesto Guevara in his

Motorcycle Diaries days. The face in the photograph is enchanting. What is the

punctum in this photograph, an "element which rises from the scene, shoots out of it like an arrow, and pierces me" (Roland Barthes,

Camera Lucida, Trans. Richard Howard, NY: The Noonday Press, 1981, p. 26)? The young man's eyes and brows are caught by his photographer "at just the right degree of openness, the right density of abandonment" (Barthes, p. 59), freely and generously offered to the viewer. The photographer has found "the

right moment, the

kairos of desire" (Barthes, p. 59).

To this day, Iran, unlike the United States and other rich countries, is a nation where the ruling class are fatter than the working class. Ahmadinejad is slight, almost diminutive, which makes him look exactly like a civil engineer that he is.

His well-lined face is now only a faint reminder of his youthful good looks, but, with his easy smile, he is still far more pleasant to look at than the old, ugly, and corpulent Ayatollah Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, whose

face and body, like the picture of Dorian Gray, proclaim to the whole world: "I got fat on oil profits. I'm living large . . . literally."

So must the Iranian working class have thought, whose welfare is threatened by the

neoliberal economic program of Rafsanjani (who held the office of the president between 1989 and 1997) and other so-called "reformists" who backed him:

- Food and housing subsidies, as well as public education and health care continued as long as Khomeini was alive. But with the Ayatollah’s death and the election of Hashemi Rafsanjani to the presidency of Iran, neoliberal policies replaced those of the welfare state of the Khomeini years. This marked a new era; in the late 1980s, when President Rafsanjani came to power, open-market policies led to economic measures such as devaluation of the currency (which increased the cost of living for the poor), privatization (which left many workers unprotected), and the decline of social services, all of which forced many women to enter the labour market. (Roksana Bahramitash, "Islamic Fundamentalism and Women’s Economic Role: The Case of Iran," International Journal of Politics, Culture and Society 16.4, Summer 2003, p. 565)

- President Rafsanjani was very clear about its economic policy. He called for liberalization and he himself benefited from through easier borrowing and became a rich man. His neo-liberal policies increased female employment, but they did not necessarily bring more economic power to women, as is the case in the rest of the developing world. Throughout the Third World, the percentage of female labour is increasing but because of the liberalization of the economy, rising prices of basic goods and welfare reduction have badly affected women.24 Today, there are 1.3 billion people living on less than a dollar a day and 70 percent of them are women.25 Iran is no exception: the increase in labor force participation by women may have increased, but the poverty and income disparity that has come with liberalization of the economy remain a serious challenge to female empowerment. The fact that there are more women in the labor force in Iran is important because it does give them some degree of autonomy. But rising prices of basic goods and cutbacks on social spending have hindered the growth of women’s economic autonomy by undermining their decision-making power. (Roksana Bahramitash, "Revolution, Islamization, and Women’s Employment in Iran," The Brown Journal of World Affairs 9.2, Winter/Spring 2003, p. 238)

That is a trend readily observable in many countries, neoliberalism being a global phenomenon.

It is not the reformists' promise of freedom of expression and association that the Iranian working class rejected in the presidential election this year. "Assuming that all of the votes cast for the other rightwing candidates in the first round went to Ahmadinejad in the runoff; he still had to attract an additional five million reform and progressive votes to end up with a seven million winning margin in the final tally," as Ahmad Sadri points out ("Exact Opposite of Paranoia,"

Iranian.com,

28 Jun. 2005 /

ZNet,

30 Jun. 2005). What they refused to tolerate any longer is deteriorating economic conditions that neoliberalism brought them, which Michael Slackman ably documents below.

They had come from very different neighborhoods and backgrounds, but they were all there for the same reason: to buy government-subsidized food.

The line ran from the basement up the stairs and out the door.

Inside, sugar and rice were selling for about one-fifth of the retail price, a huge savings in a country where according to an opposition economist more than a quarter of the people live below the poverty line - which is defined as a family of five with an income of less than $278 a month.

"I cannot make ends meet," said Hossein Ganji, 49, who works behind a counter in the food distribution center. Mr. Ganji supports his wife and three children on about $150 a month.

"I am the only person that works in my family," he said. "All the others are unemployed."

This distribution center in a crowded basement in southern Tehran and many others like it around the country represent the kind of government assistance that many people here want more of -- and that Mahmoud Ahmadinejad promised to provide in his successful campaign to become the next president of Iran.

Mr. Ahmadinejad, who catapulted to president-elect from near obscurity as the appointed mayor of Tehran, campaigned on a populist message, promising to redistribute the nation's wealth, hold down prices, raise salaries and lift state-supported benefits for the poor. He infused those pledges with the theme of social justice, which resonated in a society where aiding the poor is considered an obligation for the faithful.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Average salaries run about $200 a month in Iran, with a salary of $300 to $500 considered generous. But costs are fast outstripping the ability to pay -- government figures put annual inflation at about 15 percent, though on some products, merchants say prices rise far faster than that.

In a food store in central Tehran, the owner, Reza Karimi, said pomegranate paste had doubled in price to nearly $2; a bottle of olive oil rose to about $4 from $3, and in the last three months a little more than a pound of rice climbed to $1.80 from $1.30.

The price of dairy products sold by a state-owned company jumped 17 percent on Wednesday alone, he said. "The prices will jump again next month," he said. "And when one company raises their prices, they all do."

Khodabaksh Jalili, 30, is typical of many people in southern Tehran who supported Mr. Ahmadinejad. He moved to the city from Asadabad, a village 200 miles west of Tehran, when the farm that had supported his family for generations failed because of drought and a shortage of supplies, he said.

He has a wife and two children and earns about $200 a month working in a food store. His rent is $50 a month, and he makes extra money on his day off ferrying passengers on his scooter. If he is lucky, he said, he takes in another $20 a month.

"I have very little," he said. "I am married eight years. I have never been to the cinema with my children."

Iran is awash in oil money, as the price of crude topped $60 a barrel this week, pumping billions into the government treasury. But this country's economy is still tied down by a system in which the state and a shadowy collection of foundations controlled by clerics monopolize the vast bulk of its industries, including oil.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Rahim Oskui, who described himself as an opposition economist working for the Industrial Management Institute, a quasi-governmental agency, said the official figures of 10 percent unemployment and 27 percent living in poverty were most likely understated.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Hamid Shahrabi, 31, is the kind of person Mr. Oskui was talking about. Because of Mr. Ahmadinejad's economic message, he said, he got involved in politics for the first time. "I never voted in a presidential election before," Mr. Shahrabi said. "This guy put his hand on the Koran and said he would work for poor people - so I worked for him and voted for him."

Mr. Shahrabi lives with his wife, Azam, 30, and two small children in a one-room apartment in southeastern Tehran. There is no furniture in the living room, just a carpet on the concrete floor, a few pillows along the walls and a small television on a stand. They turned a walk-in closet into a separate bedroom, where their 12-year-old daughter sleeps and where they keep their bed cushions during the day. On any given day, the family's refrigerator is almost empty, but for a pot of traditional Iranian stew -- a mix of rice, meat and vegetables -- three-day-old bread and some tomatoes. They survive on their government rations.

Mr. Shahrabi moved to the city from Arak, a province in central Iran, when he was 15 years old, following his brothers in search of work when the family farm was no longer making enough money. He found a job with a state-owned oil company, which he kept until he was laid off four years ago. He has not found work since, and rides around the city on his battered motor scooter making deliveries and carrying passengers for about $5 a day. Of that he has to set aside $3 a day for rent.

"I feel really ashamed in front of my family," Mr. Shahrabi said, without a trace of self-pity. "My doctor said I need to feed my daughter better. I cannot afford to buy my wife new dresses. My son always feels dizzy. The landlord has asked me to find another place to live."

The Ahmadinejad campaign message of economic hope -- as well as social justice -- captured the hearts not only of people like Mr. Shahrabi but also of middle-class families. Parts of the middle class have trouble meeting their own financial needs, although their support for Mr. Ahmadinejad also stems from having grown used to buying subsidized food, even if they can afford to pay market prices. (Michael Slackman, "For the Poor in Iran, Voting Was About Making Ends Meet," New York Times, 3 Jul. 2005)

It is not clear if Iran's new president has what it takes to radically improve the conditions of working-class Iranians to whom he gave economic hope, but the way he lived his life as the mayor of Teheran suggests that those who voted for him had a good reason to believe that he won't get fat at their expense:

[F]riends, supporters and neighbors here describe the diminutive, bearded man as humble and caring. Mr. Ahmadinejad has a small circle of aides, one that appears a bit overwhelmed by all the demands and preparations ahead. Nasser Hadian-Jazy, a political science professor at Tehran University, said that he had known the president-elect since childhood and that Mr. Ahmadinejad was not involved with the student hostage takers. He said they grew up together in East Tehran, and Mr. Hadian-Jazy described his old classmate as among the brightest in the neighborhood.

He called Mr. Ahmadinejad "self-confident, committed and absolutely incorruptible." He said he is very religious, but modern in his thinking. If there is a negative quality, Mr. Hadian-Jazy said, it is that he is very set in his views, and can be hard to persuade otherwise.

"If you can force him to sit down and listen, he has the capability to understand," the professor said.

While Mr. Ahmadinejad maintained a humble life style as the appointed mayor of Tehran, that is likely to change, if for no other reason than security. He lives at the end of a dead-end street, more of an alley that runs alongside a school. The alley opens onto a circle, with a small park in the middle with benches and a field of grass that now attracts those who come to ask favors of the president-elect, and serves as a spot for neighbors to socialize. These days, cars packed with sightseers drive around the circle, stopping to look down the alley, a far cry from the palatial and off-limit homes of other Iranian leaders.

On Friday, the day of prayer and rest in most Muslim countries, some of Mr. Ahmadinejad's neighbors sat on a bench, talking about their favorite son. It is almost a rule that when someone is asked about Mr. Ahmadinejad, the first thing said is that he is a modest person who has never lost touch with his roots. Security is very tight in the neighborhood, and with soldiers and plainclothes agents around, the neighbors were afraid to give their names.

One older man, who said he had lived in the neighborhood for 15 years, said that every year for the Iranian New Year, Mr. Ahmadinejad invited the neighbors over for a celebration. He is described as a devout man who lives in a three-bedroom house with two sons and a daughter. His family has little furniture, they said, and has machine-made carpets, not the more expensive hand-woven ones commonly owned by the better-off.

One son is finishing high school, and the two other children are studying in the university, the neighbors said.

Since he became mayor of Tehran, the city has had a driver pick Mr. Ahmadinejad up for work every day. But on his days off, neighbors said, he still drives the same 1977 Peugeot, without air-conditioning, that is parked in the alleyway beside the house.

People are quick to offer stories about Mr. Ahmadinejad, almost as if he was a religious figure. They say, for example, that he always brought his own lunch to work because he did not want the city to have to pay for his meals.

At the municipal building, Ahmad Esmali's job is to deliver tea to the offices. "This mayor was better than the others," he said recently. "He saw managers and workers with one eye."

In the park on Friday, one neighbor said the mayor had given money to the local butcher, at a shop called Zand, so the butcher could give poor and needy people meat at a discount. Two young men working in the butcher shop said they believed it was true.

It is a common practice in many Middle Eastern cultures for leaders to have audiences with citizens seeking help, or to accept their petitions for assistance. Mr. Ahmadinejad appears to take that custom to heart.

A small security booth sits at the mouth of the alley leading to his house. As Mr. Ahmadinejad's car pulled out, a security agent handed the president-elect a pile of letters that had been delivered that morning, from people seeking some kind of help.

Ali Ghorbani, 29, had just driven up to deliver a letter to the guard booth when Mr. Ahmadinejad pulled up. Mr. Ghorbani wanted to ask for a loan so he and a friend could open a cultural center in Tehran. He was allowed to hand the letter directly to the president-elect. "I didn't have the faintest idea I would see him," Mr. Ghorbani said as he walked away. "He took the letter and told me I would have a reply in two weeks." (Michael Slackman, "Iranian Leader Denies He Took Embassy Hostages," New York Times, 2 Jul. 2005)

Update* A spokesman for the Austrian public prosecutor's office, Ernst Kloiber, appears to find the allegation (that Mahmoud Ahmadinejad was involved in the 1989 assassination in Vienna of Abdul Rahman Ghassemlou, leader of the Kurdistan Democratic Party of Iran) doubtful.

Kloiber cast doubt on the strength of the journalist's testimony.

"According to our information, he has third-hand information on the murder," Kloiber said. "It would therefore be very difficult" to open an investigation against Ahmadinejad, he said. (Agence France-Presse, "Austria Seeks to Interview Journalist over Ahmadinejad Murder Accusations," 5 Jul. 2005)

The "journalist" is said to be an unnamed Iranian whom the Austrian Green party's spokesman on security, Peter Pilz, claims to have "met on May 20 in Versailles, France" (Agence France-Presse,

5 Jul. 2005). Sounds like a potboiler concocted by the

Fake News machine.

Venezuela has won its battle for universal literacy, thanks to Cuba's assistance: "The two-year Robinson Mission, in the process of concluding, has taught 1.5 million adults learn to read, while Robinson Mission II will help those without prior opportunity to study to reach a sixth grade level, and the Ribas and Sucre programs are concentrating on university education" ("Venezuela´s New Independence Day," Prensa Latina, 5 Jul. 2005).

Venezuela has won its battle for universal literacy, thanks to Cuba's assistance: "The two-year Robinson Mission, in the process of concluding, has taught 1.5 million adults learn to read, while Robinson Mission II will help those without prior opportunity to study to reach a sixth grade level, and the Ribas and Sucre programs are concentrating on university education" ("Venezuela´s New Independence Day," Prensa Latina, 5 Jul. 2005).The initiative, called Petrocaribe, would extend and improve special financing arrangements under past oil deals and use an expanded fleet of Venezuelan tankers to deliver fuel directly to bypass costly intermediaries, Chavez said.